Last night’s successful Starlink launch was a big one for SpaceX — its heaviest payload ever, weighed down by 60 communications satellites that will eventually be part of a single constellation providing internet to the globe. That’s the plan, anyway — and the company pulled the curtain back a bit more after launch, revealing a few more details about the birds it just put in the air.

SpaceX and CEO Elon Musk have been extremely tight-lipped about the Starlink satellites, only dropping a few hints here and there before the launch. We know, for instance, that each satellite weighs about 500 pounds, and are a flat-panel design that maximized the amount that can fit in each payload. The launch media kit also described a “Startracker” navigation system that would allow the satellites to locate themselves and orbital debris with precision.

At the fresh new Starlink website, however, a few new details have appeared, alongside some images that provide the clearest look yet (renders, not photographs, but still) of the satellites that will soon number thousands in our skies.

In the CG representation of how the satellites will work, you get a general sense of it:

Thousands of satellites will move along their orbits simultaneously, each beaming internet to and from the surface in a given area. It’s still not clear exactly how big an area each satellite will cover, or how much redundancy will be required. But the image gives you the general idea.

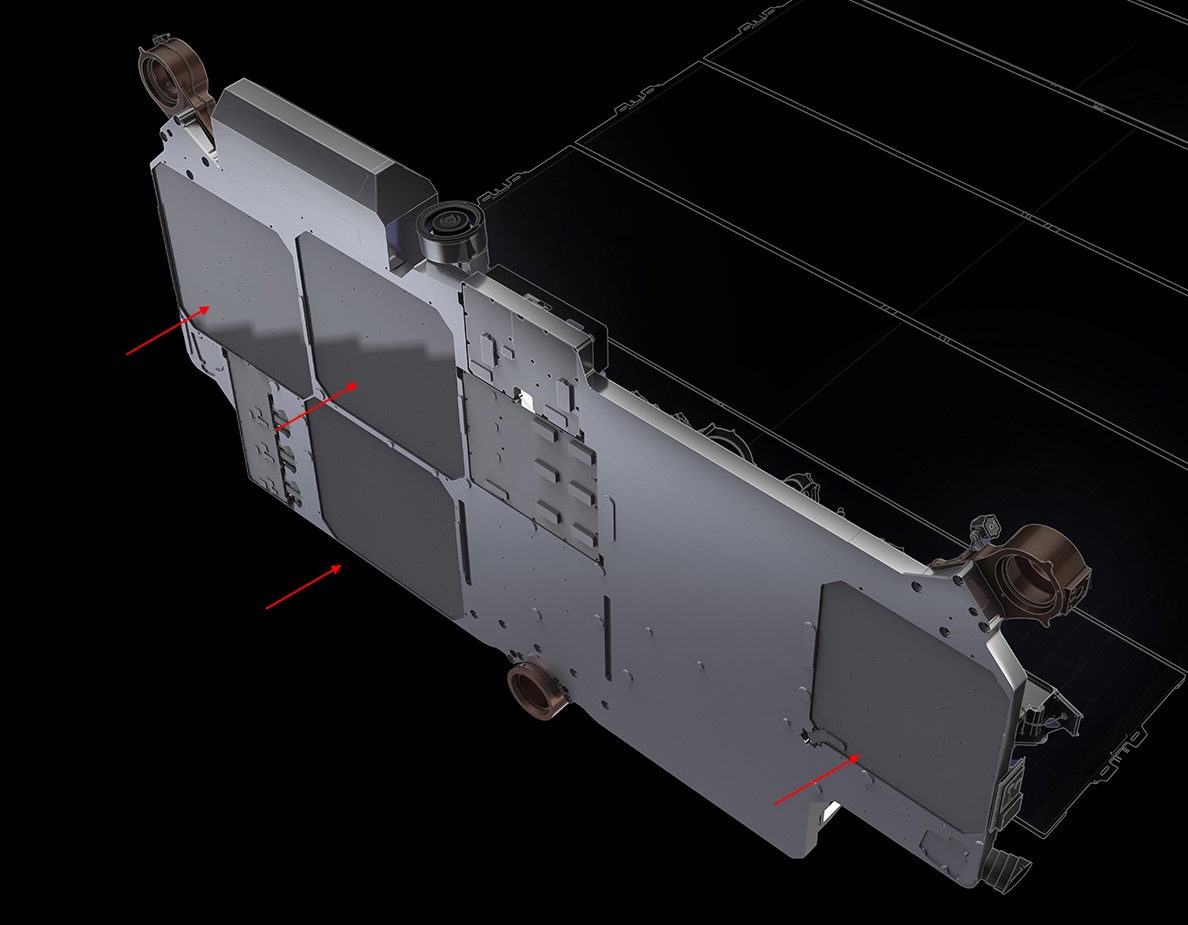

The signal comes from and goes to a set of four “phased array” radio antennas. This compact, flat type of antenna can transmit in multiple directions and frequencies without moving like you see big radar dishes do. There are costs as well, but it’s a no-brainer for satellites that need to be small and only need to transmit in one general direction — down.

There’s only a single solar array, which unfolds upwards like a map (and looks pretty much like you’d expect — hence no image here). The merits of having only one are mainly related to simplicity and cost — having two gives you more power and redundancy if one fails. But if you’re going to make a few thousand of these things and replace them every couple years, it probably doesn’t matter too much. Solar arrays are reliable standard parts now.

There’s only a single solar array, which unfolds upwards like a map (and looks pretty much like you’d expect — hence no image here). The merits of having only one are mainly related to simplicity and cost — having two gives you more power and redundancy if one fails. But if you’re going to make a few thousand of these things and replace them every couple years, it probably doesn’t matter too much. Solar arrays are reliable standard parts now.

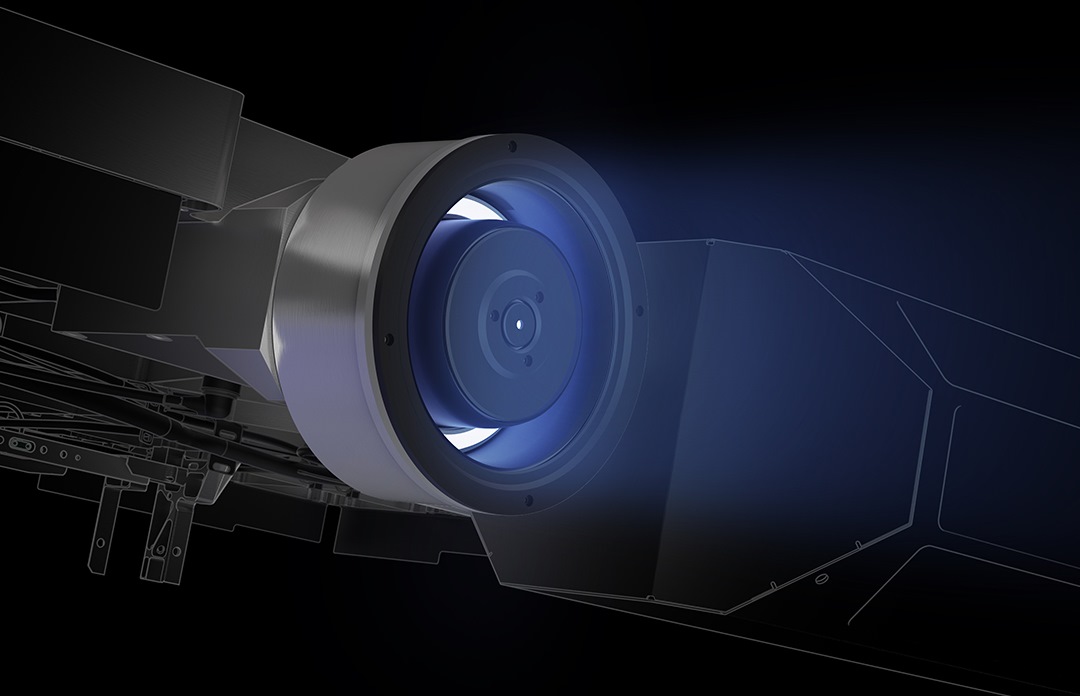

The krypton-powered ion thruster sounds like science fiction, but ion thrusters have actually been around for decades. They use a charge difference to shoot ions — charged molecules — out in a specific direction, imparting force in the opposite direction. Kind of like a tiny electric pea shooter that, in microgravity, pushes the person back with the momentum of the pea.

To do this it needs propellant — usually xenon, which has several (rather difficult to explain) properties that make it useful for these purposes. Krypton is the next Noble gas up the list in the table, and is similar in some ways but easier to get. Again, if you’re deploying thousands of ion engines — so far only a handful have actually flown — you want to minimize costs and exotic materials.

To do this it needs propellant — usually xenon, which has several (rather difficult to explain) properties that make it useful for these purposes. Krypton is the next Noble gas up the list in the table, and is similar in some ways but easier to get. Again, if you’re deploying thousands of ion engines — so far only a handful have actually flown — you want to minimize costs and exotic materials.

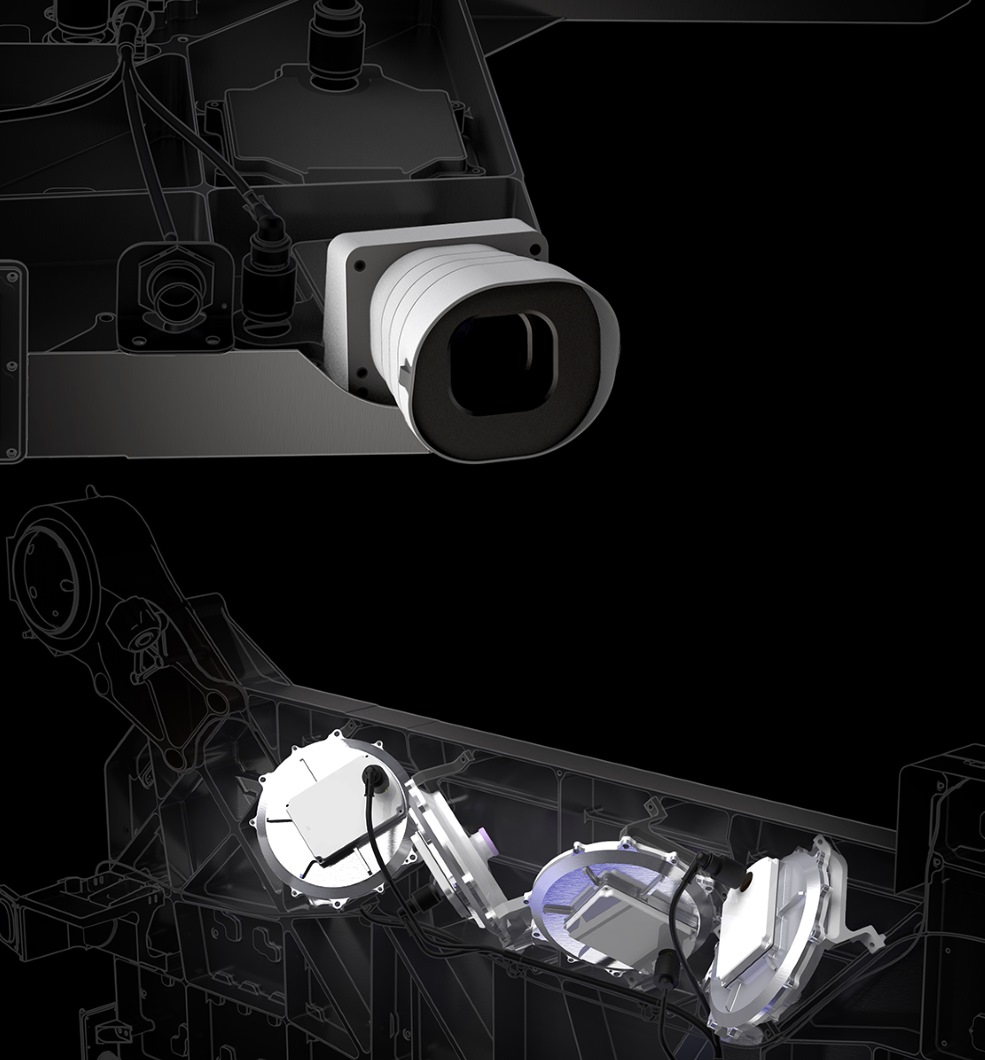

Lastly there is the Star Tracker and collision avoidance system. This isn’t very well explained by SpaceX, so we can only surmise based on what we see. The star tracker tells each satellite its attitude, or orientation in space — presumably by looking at the stars and comparing that with known variables like time of day on Earth and so on. This ties in with collision avoidance, which uses the government’s database of known space debris and can adjust course to avoid it.

Lastly there is the Star Tracker and collision avoidance system. This isn’t very well explained by SpaceX, so we can only surmise based on what we see. The star tracker tells each satellite its attitude, or orientation in space — presumably by looking at the stars and comparing that with known variables like time of day on Earth and so on. This ties in with collision avoidance, which uses the government’s database of known space debris and can adjust course to avoid it.

How? The image on the Starlink site shows four discs at perpendicular orientations. This suggests they’re reaction wheels, which store kinetic energy and can be spun up or slowed down to impart that force on the craft, turning it as desired. Very clever little devices actually and quite common in satellites. These would control the attitude and the thruster would give a little impulse, and the debris is avoided. The satellite can return to normal orbit shortly thereafter.

We still don’t know a lot about the Starlink system. For instance, what do its ground stations look like? Unlike Ubiquitilink, you can’t receive a Starlink signal directly on your phone. So you’ll need a receiver, which Musk has said in the past is about the size of a pizza box. But small, large, or extra large? Where can it be mounted, and how much does it cost?

The questions of interconnection are also a mystery. Say a Starlink user wants to visit a website hosted in Croatia. Does the signal go up to Starlink, between satellites, and down to the nearest base station? Does it go down at a big interconnect point on the backbone serving that region? Does it go up and then come down 20 few miles from your house at the place where fiber connects to the local backbone? It may not matter much to ordinary users, but for big services — think Netflix — it could be very important.

And lastly, how much does it cost? SpaceX wants to make this competitive with terrestrial broadband, which is a little hard to believe considering the growth of fiber, but also not that hard to believe because of telecoms dragging their heels getting to rural areas still using DSL. Out there, Starlink might be a godsend, while in big cities it might be superfluous.

Chances are won’t know for a long time. The 60 satellites up there right now are only the very first wave, and don’t comprise anything more than a test bed for future services. Starlink will have to prove these things work as planned, and then send up several hundred more before it can offer even the most rudimentary service. Of course, that is the plan, and might even be accomplished by the end of the year. In the meantime I’ve asked SpaceX for more details and will update this post if I hear back.

do

do