Facebook knows the historical app audit it’s conducting in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica data misuse scandal is going to result in a tsunami of skeletons tumbling out of its closet.

It’s already suspended around 200 apps as a result of the audit — which remains ongoing, with no formal timeline announced for when the process (and any associated investigations that flow from it) will be concluded.

CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced the audit on March 21, writing then that the company would “investigate all apps that had access to large amounts of information before we changed our platform to dramatically reduce data access in 2014, and we will conduct a full audit of any app with suspicious activity”.

But you do have to question how much the audit exercise is, first and foremost, intended to function as PR damage limitation for Facebook’s brand — given the company’s relaxed response to a data abuse report concerning a quiz app with ~120M monthly users, which it received right in the midst of the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

Because despite Facebook being alerted about the risk posed by the leaky quiz apps in late April — via its own data abuse bug bounty program — they were still live on its platform a month later.

It took about a further month for the vulnerability to be fixed.

And, sure, Facebook was certainly busy over that period. Busy dealing with a major privacy scandal.

Perhaps the company was putting rather more effort into pumping out a steady stream of crisis PR — including taking out full page newspaper adverts (where it wrote that: “we have a responsibility to protect your information. If we can’t, we don’t deserve it”) — vs actually ‘locking down the platform’, per its repeat claims, even though the company’s long and rich privacy-hostile history suggests otherwise.

Let’s also not forget that, in early April, Facebook quietly confessed to a major security flaw of its own — when it admitted that an account search and recovery feature had been abused by “malicious actors” who, over what must have been a period of several years, had been able to surreptitiously collect personal data on a majority of Facebook’s ~2BN users — and use that intel for whatever they fancied.

So Facebook users already have plenty reasons to doubt the company’s claims to be able to “protect your information”. But this latest data fail facepalm suggests it’s hardly scrambling to make amends for its own stinkingly bad legacy either.

Change will require regulation. And in Europe that has arrived, in the form of the GDPR.

Although it remains to be seen whether Facebook will face any data breach complaints in this specific instance, i.e. for not disclosing to affected users that their information was at risk of being exposed by the leaky quiz apps.

The regulation came into force on May 25 — and the javascript vulnerability was not fixed until June. So there may be grounds for concerned consumers to complain.

Which Facebook data abuse victim am I?

Writing in a Medium post, the security researcher who filed the report — self-styled “hacker” Inti De Ceukelaire — explains he went hunting for data abusers on Facebook’s platform after the company announced a data abuse bounty on April 10, as the company scrambled to present a responsible face to the world following revelations that a quiz app running on its platform had surreptitiously harvested millions of users’ data — data that had been passed to a controversial UK firm which intended to use it to target political ads at US voters.

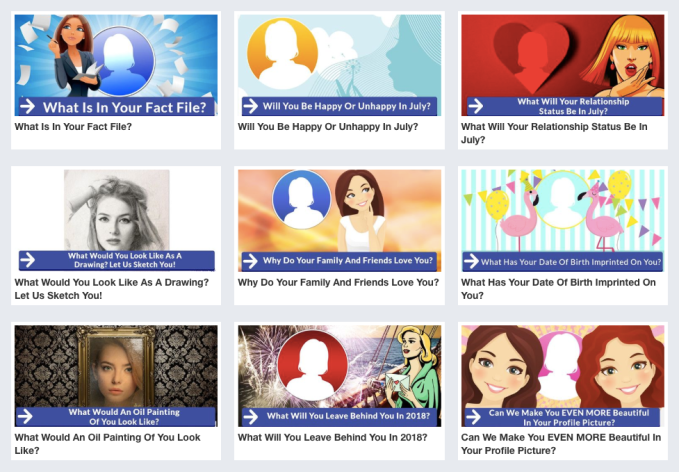

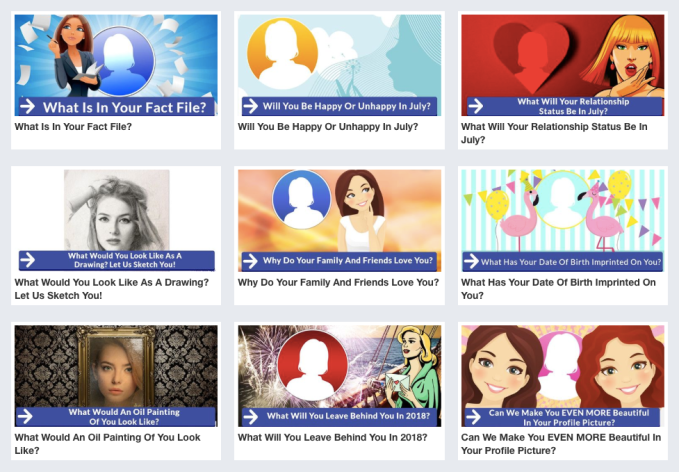

De Ceukelaire says he began his search by noting down what third party apps his Facebook friends were using — finding quizzes were one of the most popular apps. Plus he already knew quizzes had a reputation for being data-suckers in a distracting wrapper. So he took his first ever Facebook quiz, from a brand called NameTests.com, and quickly realized the company was exposing Facebook users’ data to “any third-party that requested it”.

The issue was that NameTests was displaying the quiz taker’s personal data (such as full name, location, age, birthday) in a javascript file — thereby potentially exposing the identify and other data on logged in Facebook users to any external website they happened to visit.

He also found it was providing an access token that allowed it to grant even more expansive data access permissions to third party websites — such as to users’ Facebook posts, photos and friends.

It’s not clear exactly why — but presumably relates to the quiz app company’s own ad targeting activities. (Its privacy policy states: “We work together with various technological partners who, for example, display advertisements on the basis of user data. We make sure that the user’s data is pseudonymised (e.g. no clear data such as names or e-mail addresses) and that users have simple rights of revocation at their disposal. We also conclude special data protection agreements with our partners, in which they commit themselves to the protection of user data.” — which sounds great until you realize its javascript was just leaking people’s personally identified data… [facepalm])

“Depending on what quizzes you took, the javascript could leak your facebook ID, first name, last name, language, gender, date of birth, profile picture, cover photo, currency, devices you use, when your information was last updated, your posts and statuses, your photos and your friends,” writes De Ceukelaire.

He reckons people’s data had been being publicly exposed since at least the end of 2016.

On Facebook, NameTests describes its purpose thusly: “Our goal is simple: To make people smile!” — adding that its quizzes are intended as a bit of “fun”.

It doesn’t shout so loudly that the ‘price’ for taking one of its quizzes, say to find out what Disney princess you ‘are’, or what you could look like as an oil painting, is not only that it will suck out masses of your personal data (and potentially your friends’ data) from Facebook’s platform for its own ad targeting purposes but was also, until recently, that your and other people’s information could have been exposed to goodness knows who, for goodness knows what nefarious purposes…

The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data misuse scandal has underlined that ostensibly frivolous social data can end up being repurposed for all sorts of manipulative and power-grabbing purposes. (And not only can end up, but that quizzes are deliberately built to be data-harvesting tools… So think of that the next time you get a ‘take this quiz’ notification asking ‘what is in your fact file?’ or ‘what has your date of birth imprinted on you’? And hope ads is all you’re being targeted for… )

De Ceukelaire found that NameTests would still reveal Facebook users’ identity even after its app was deleted.

“In order to prevent this from happening, the user would have had to manually delete the cookies on their device, since NameTests.com does not offer a log out functionality,” he writes.

“I would imagine you wouldn’t want any website to know who you are, let alone steal your information or photos. Abusing this flaw, advertisers could have targeted (political) ads based on your Facebook posts and friends. More explicit websites could have abused this flaw to blackmail their visitors, threatening to leak your sneaky search history to your friends,” he adds, fleshing out the risks for affected Facebook users.

As well as alerting Facebook to the vulnerability, De Ceukelaire says he contacted NameTests — and they claimed to have found no evidence of abuse by a third party. They also said they would make changes to fix the issue.

We’ve reached out to NameTests’ parent company — a German firm called Social Sweethearts — for comment. Its website touts a “data-driven approach” — and claims its portfolio of products achieve “a global organic reach of several billion page views per month”.

After De Ceukelaire reported the problem to Facebook, he says he received an initial response from the company on April 30 saying they were looking into it. Then, hearing nothing for some weeks, he sent a follow up email, on May 14, asking whether they had contacted the app developers.

A week later Facebook replied saying it could take three to six months to investigate the issue (i.e. the same timeframe mentioned in their initial automated reply), adding they would keep him in the loop.

Yet at that time — which was a month after his original report — the leaky NameTests quizzes were still up and running, meaning Facebook users’ data was still being exposed and at risk. And Facebook knew about the risk.

The next development came on June 25, when De Ceukelaire says he noticed NameTests had changed the way they process data to close down the access they had been exposing to third parties.

Two days later Facebook also confirmed the flaw in writing, admitting: “[T]his could have allowed an attacker to determine the details of a logged-in user to Facebook’s platform.”

It also told him it had confirmed with NameTests the issue had been fixed. And its apps continue to be available on Facebook’s platform — suggesting Facebook did not find the kind of suspicious activity that has led it to suspend other third party apps. (At least, assuming it conducted an investigation.)

Facebook paid out a $4,000 x2 bounty to a charity under the terms of its data abuse bug bounty program — and per De Ceukelaire’s request.

We asked it what took it so long to respond to the data abuse report, especially given the issue was so topical when De Ceukelaire filed the report. But Facebook declined to answer specific questions.

Instead it sent us the following statement, attributed to Ime Archibong, its VP of product partnerships:

A researcher brought the issue with the nametests.com website to our attention through our Data Abuse Bounty Program that we launched in April to encourage reports involving Facebook data. We worked with nametests.com to resolve the vulnerability on their website, which was completed in June.

Facebook also claims it received De Ceukelaire’s report on April 27, rather than April 22, as he recounts it. Though it’s possible the former date is when Facebook’s own staff retrieved the report from its systems.

Beyond displaying a disturbingly relaxed attitude to other people’s privacy — which risks getting Facebook into regulatory trouble, given GDPR’s strict requirements around breach disclosure, for example — the other core issue of concern here is the company’s apparent failure to enforce its own developer policy.

The underlying issue is whether or not Facebook performs any checks on apps running on its platform. It’s no good having T&Cs if you don’t have any active processes to enforce your T&Cs. Rules without enforcement aren’t worth the paper they’re written on.

Historical evidence suggests Facebook did not actively enforce its developer T&Cs — even if it’s now “locking down the platform”, as it claims, as a result of so many privacy scandals.

The quiz app developer at the center of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, Aleksandr Kogan — who harvested and sold/passed Facebook user data to third parties — has accused Facebook of essentially not having a policy. He contends it is therefore Facebook who is responsible for the massive data abuses that have played out on its platform — only a portion of which have so far come to light.

Fresh examples such as NameTests’ leaky quiz apps merely bolster the case Kogan made for Facebook being the guilty party where data misuse is concerned. After all, if you built some stables without any doors at all would you really blame your horses for bolting?