Amazon might have the monopoly on physical goods sold online. But what about digital ones?

There’s Steam for games and software. Shopify supports some forms of digital goods, like artwork and gig services. But three co-founders, Steven Schwartz, Cameron Zoub and Jack Sharkey, believe that there’s room for competition.

Schwartz, Zoub and Sharkey are the creators of Whop, a marketplace for people to sell access to digital products. Products for sale — and re-sale — run the gamut from sports gambling picks and deals on food, travel and credit cards to tips to “level up your social game.”

“Whop is a comprehensive online platform aimed at connecting sellers and buyers within the digital economy,” Schwartz told TechCrunch in an email interview. “Its mission is to centralize all products on the internet, offering a one-stop solution for anyone looking to participate in the digital economy.”

Zoub and Schwartz met when they were 13 years old in a Facebook group over a shared interest in limited-edition sneakers. Together, they launched one of the first “sneaker bots” — software to get shoes before they sold out — and used the profits to bootstrap the creation of more software to sell online.

After teaming up with Sharkey, a software developer, to build products for small businesses, Zoub and Schwartz created a makeshift marketplace where people could buy software — and sell their own — for free. But scammers overran it.

“It was trash,” Schwartz said bluntly. “People had to make forum posts and often got scammed, a middleman was required and pricing for the software wasn’t clear.”

So Schwartz, Zoub and Sharkey began working on an improved version of the marketplace, which became Whop.

“We’re creating a new economy, giving people new things to sell,” Schwartz said. “We see ourselves as competing with social media, where people have traditionally gone to sell their software, but suffer through an incredibly suboptimal experience.”

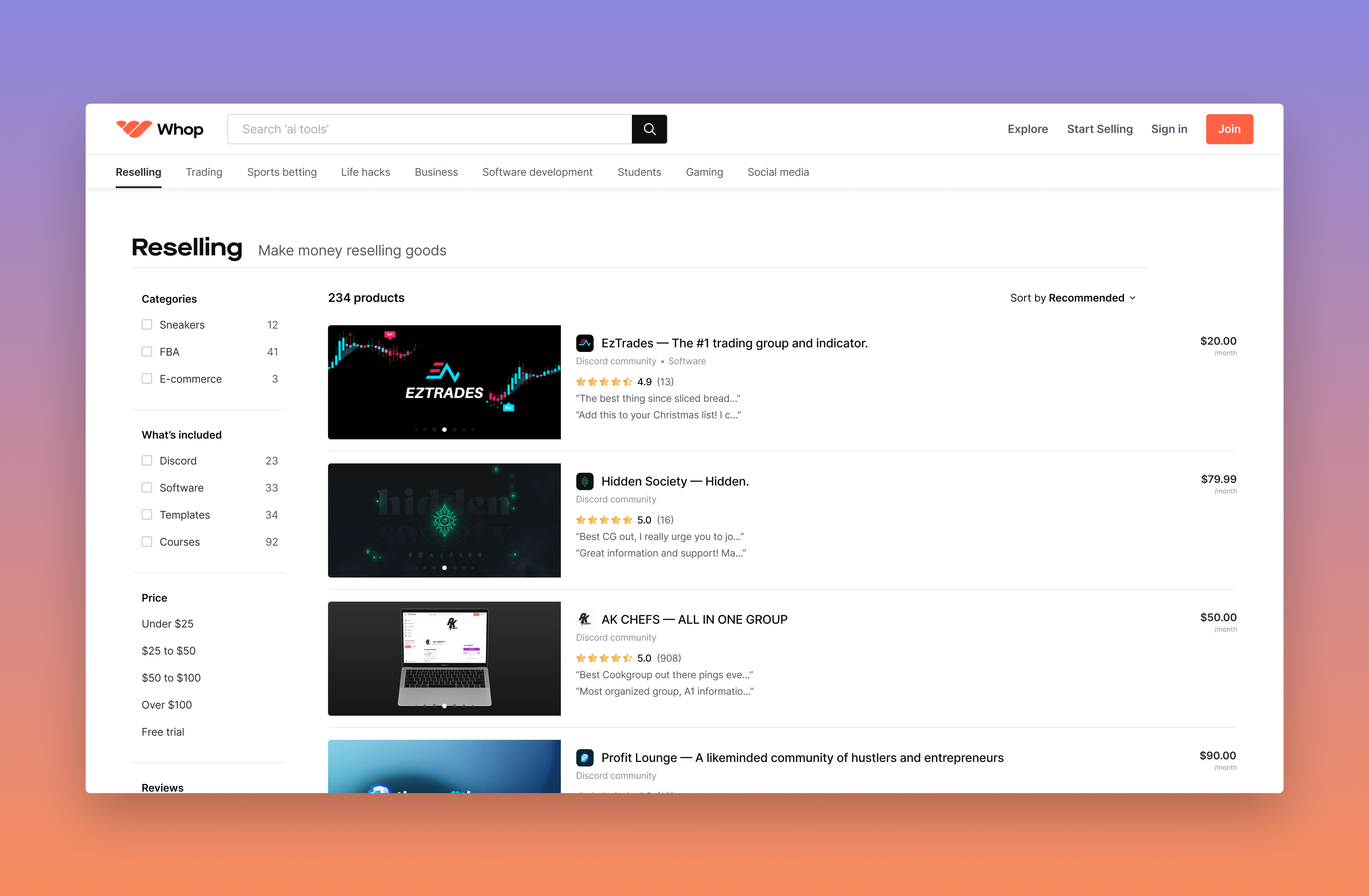

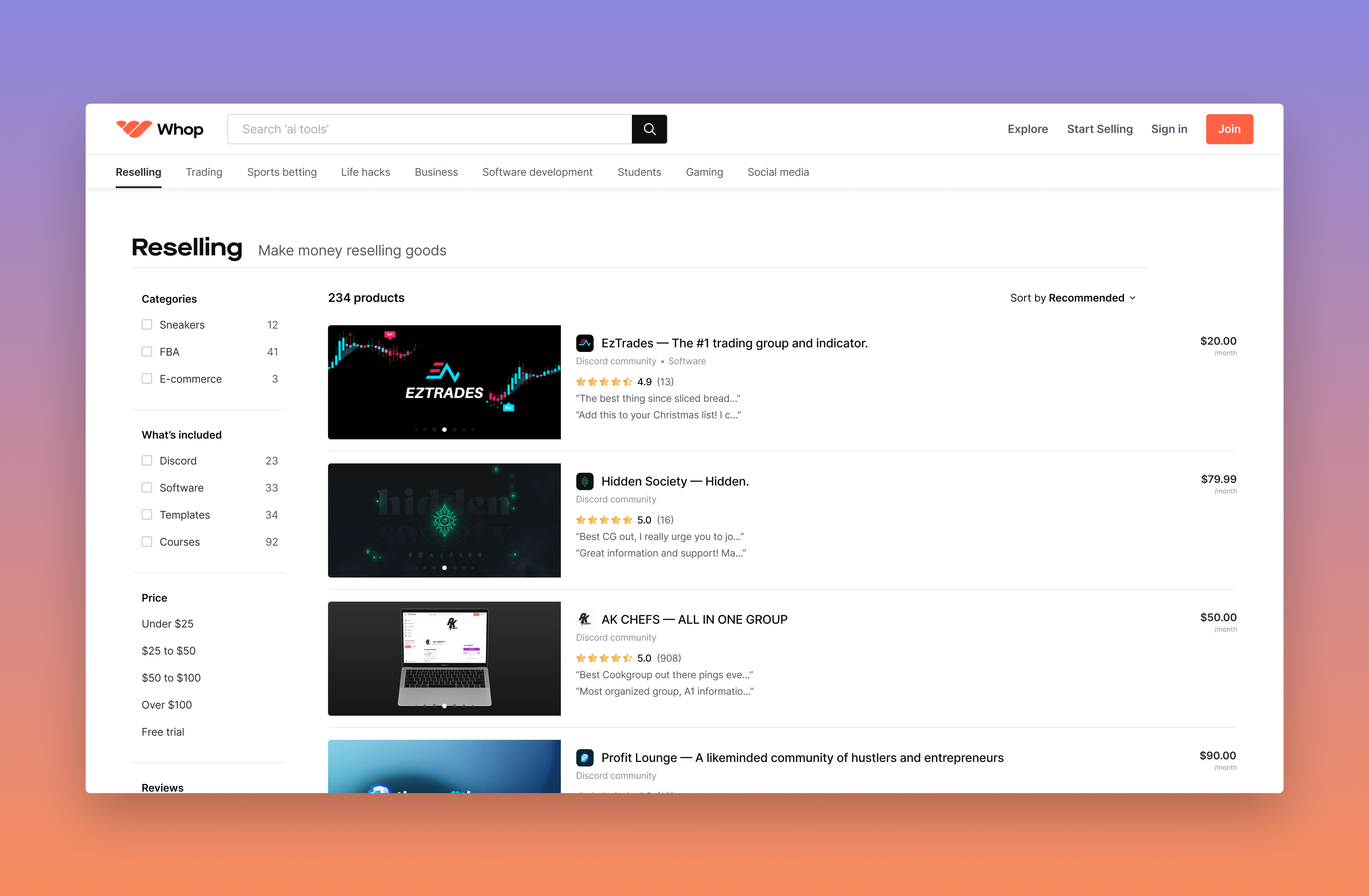

Whop’s online marketplace for digital goods and services selling.

Given the countless goods and services marketplaces out there, one might wonder what makes Whop — besides the amusing name — different. (This writer did.) Schwartz claims that Whop is differentiated by its selling experience and product discovery engine.

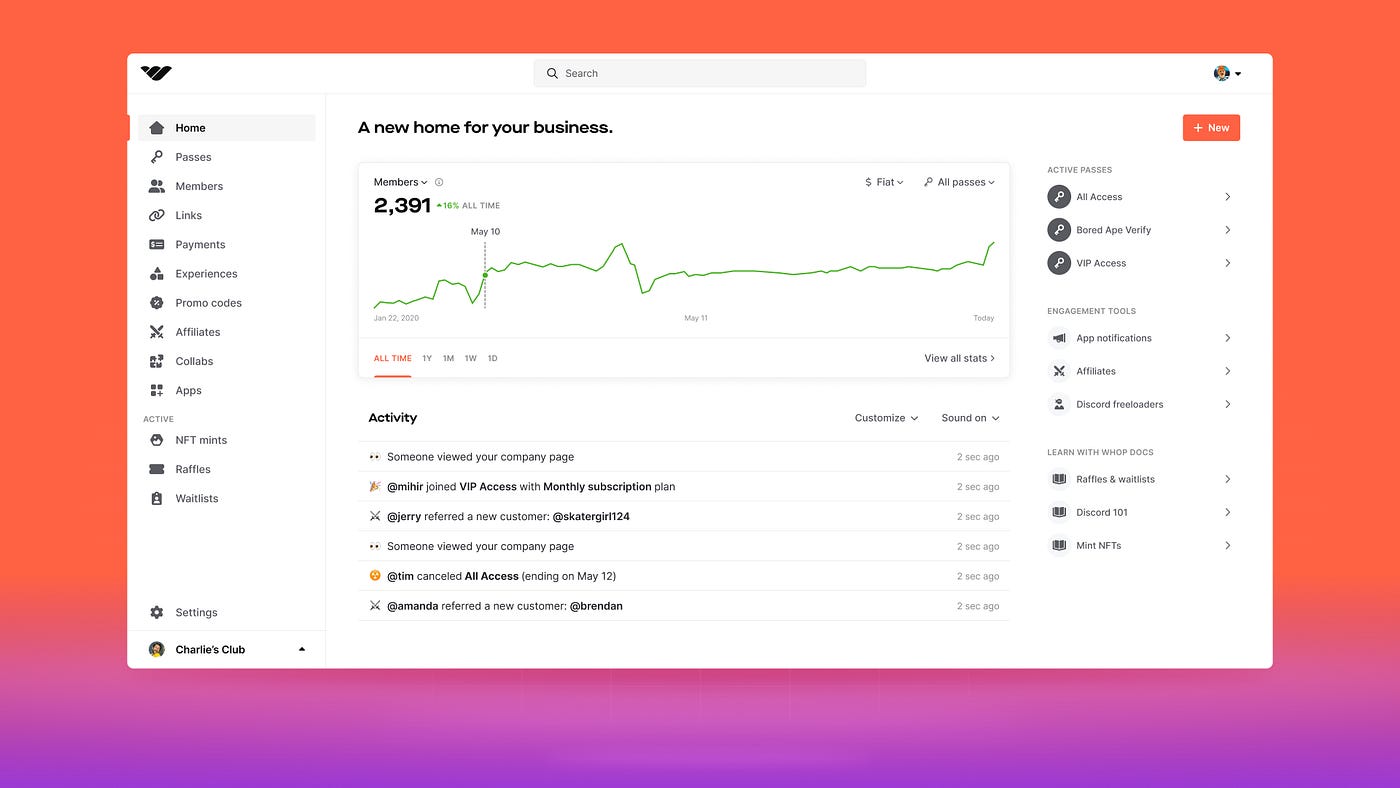

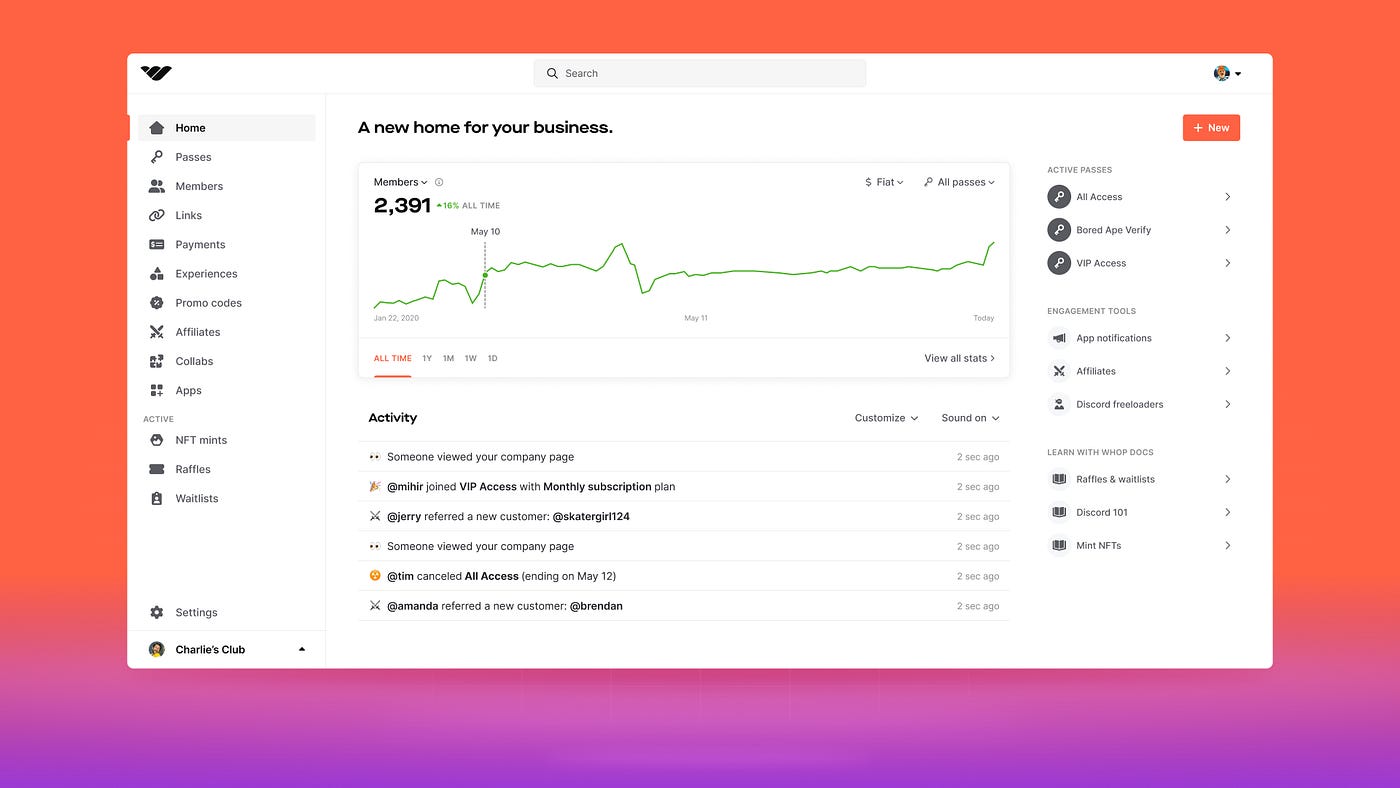

Sellers on Whop get a dashboard with promotion and customer relationship management tools as well as analytics for business insights. As for buyers, they’re treated to a recommendation algorithm, visualizations for discovering new products and a portal for managing their purchases.

Sound par for the course? Perhaps. But Whop’s going after a different audience than your typical marketplace: influencers and content creators.

“People are selling sponsorships or ad space on traditional social channels, but now they can use Whop to offer their audience a real, living and breathing product that they can collect a recurring, stable income stream on,” Schwartz said. “If someone has a million followers, they think they’re better off continuing to post content, but in reality, someone who has 20,000 followers with a real product is actually making more money than them.”

Is there truth to that last statement? Perhaps. What does appear to be a trend is that buyers are more likely to buy a product that’s recommended to them by an influencer they trust. According to one source, 49% of consumers depend on influencer recommendations, while 40% say that they’re likely to purchase something after seeing it on Twitter, YouTube or Instagram.

In my cursory browsing, a lot of Whop’s listings seem to revolve around sports betting, crypto and general wealth-growing strategies. There’s nothing wrong with that, necessarily. But I wonder if it all has staying power — and how carefully it’s moderated.

Whop provides analytics to sellers on the backend.

As with all marketplaces, there’s a risk, also, that bad actors manipulate the platform to drive sales to scammy products — whether through fake reviews or dubious SEO practices. Whop says that it takes steps to mitigate this, but it’s tough to know how extensive those steps are, particularly considering Whop’s small team (20 people).

But investors see potential in what Whop’s doing. The company today announced that it raised $17 million in a Series A round with participation from Insight Partners, The Chainsmokers, Peter Thiel and others. The tranche values the startup at over $100 million — a healthy valuation for a marketplace of around a million customers and 3,000 sellers that’s done $100 million in transactions to date.

“We have loads of runway,” Schwartz said. “The pandemic and slowdown in tech have been incredible for us; the slowdown in venture in particular has resulted in numerous small-scale, cash-focused products, which is exactly what our product supports.”