Our team of researchers started CoCoPIE to solve the chip shortage crisis. We’re a group of Ph.D.s who aim to power next-generation technology without the need for expensive hardware that takes billions of dollars to develop and years to deploy. We needed a way to bring our idea into action.

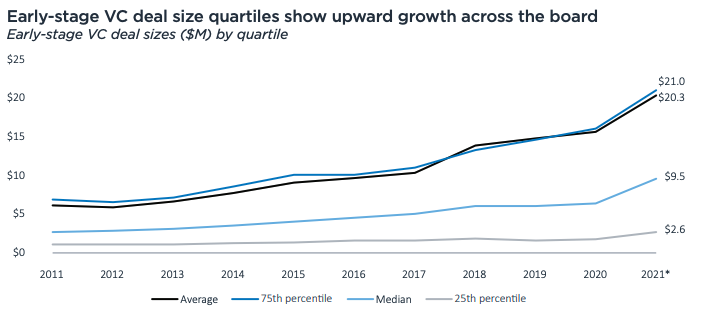

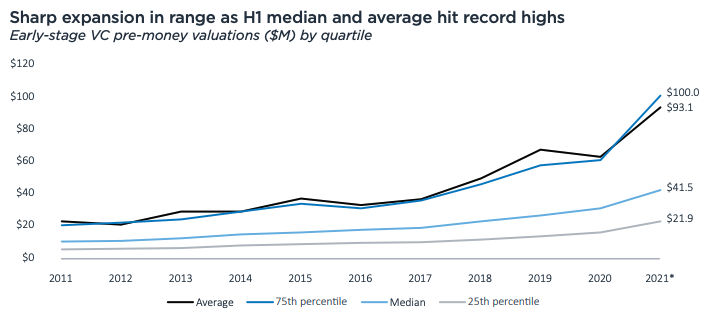

For deep tech startups, the capital game can be a tricky one to play. The VC world is attracted to the low-investment/high-returns model deep tech tends to offer, but it can also be impatient with the time it takes to get there. According to PitchBook, the VC world is also trending toward the megadeal ($100 million+), which doesn’t generally apply to early-stage startups with a handful of employees.

While we did raise funds from one of the VC world’s glitterati — Sequoia Capital — when we were accepted into the Small Business Innovation Research/Small Business Technology Transfer (SBIR/STTR) program, we knew our solution was much more valuable than a chip that would make its way to the reject line.

Here’s why we applied for a federal grant and why we think you should add “America’s Seed Fund” to your deep tech fundraising mix.

Build credibility

There are several SBIR/STTR programs. Ours is powered by the National Science Foundation. These grants are highly competitive and, if chosen, can establish and strengthen your company’s technical image on the market.

Being selected out of thousands of U.S. applicants signals that your innovation has strong technical and commercial merit and the potential for broad U.S. economic impact. It’s a stamp that encourages other potential investors to raise their hands. Even if you aren’t selected, the feedback you receive from the review committee is invaluable.

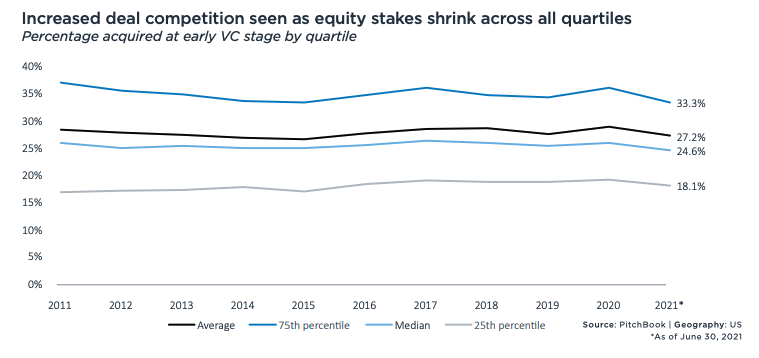

Keep equity and decision-making authority

Receiving funding often means you have to give something back. That can be interest payments if you’ve taken a loan or equity if you’ve received VC funds. The SBIR/STTR programs allow you to retain full ownership of your company and IP. The administrators also aren’t interested in driving strategy — they believe in your vision and want to help you bring it to fruition. Their goal is to “invest in a better future for our shareholders: the American public.”

CoCoPIE’s vision is to enable real-time AI for off-the-shelf mobile devices. If adopted by the semiconductor, digital media and IoT industries, it can significantly improve the way we consume, learn and interact with our devices.

But, like any deep tech company, the question becomes how to get it widely adopted. We are using the SBIR/STTR funds to convert our technology into a minimum viable product, an essential step for us to reach a broader customer base. Thus far, our technology has attracted multiple key pilot customers, including Tencent, a global gaming giant that utilizes our super-resolution technology to enhance its customers’ gaming experience.

Potential for additional funding

The SBIR/STTR program is administered in three gated phases that progress your product toward commercialization. Each startup can receive up to $2 million in funding. What you don’t get in funding in Phase III you make up for in actual business, typically through government procurement contracts.