Like many ambitious Chinese who graduated college abroad during the 2010s and aspired to be the next Jack Ma or Pony Ma, Lucas returned to his motherland to build his own internet startup. Two years into running the business, however, his enthusiasm has waned. The regulatory risks and compliance costs affecting his company have become too high to justify building a China-centric product, prompting him to look abroad for growth.

(Lucas is the founder’s pseudonym due to the sensitivity of discussing regulations. We are unable to specify what his company does as that would compromise his identity.)

In the past few years, China has introduced a litany of policies to assert more control over its internet sector. Verticals from fintech, social media, gaming, e-commerce to live streaming have increasingly come under regulatory fire for their unscrupulous growth and the social issues they produce. Now, that scrutiny is propelling startups that had once thought they had a future for funding and growth in China to go overseas.

Observers argue that the crackdown on consumer internet giants like Alibaba and Didi is meant to spur domestic innovation in “hard” technology, like semiconductors and industrial robots, that will help China compete on the global stage. Beijing wants to curb the power of internet giants, especially those generating structural problems like lending products that put young consumers in debt, games that cause addiction, and online education services that widen the wealth gap.

Such policies may have initially set out to rein in the internet behemoths, but they have also ended up crippling the growth of budding startups like Lucas’s, which face mounting compliance costs and operational hurdles in China.

Three other China-founded consumer internet startups that spoke with TechCrunch said they are also leaving the Chinese market behind due to heightened regulatory uncertainty. Four investors told us that portfolio companies that focus on online education, fintech, and video games are making a similar pivot to target international users.

While Web3-focused entrepreneurs from across the road are racing to revolutionize the digital space, the industry has fallen out of the picture in China, where strict censorship and a sweeping ban on cryptocurrency have eliminated the potential for decentralized services, which are at the core of Web3, to thrive. The fear that another vertical may face clampdown looms large in China’s startup community.

Tightening grip

Regulations targeting tech companies are nothing new in China, but for years, many policies were vaguely phrased or not enforced. “The authorities were keeping one eye closed when things used to be laxer,” said Lucas.

For the vigilant entrepreneurs, Beijing’s shelving of Ant Group’s initial public offering in 2020 was the first alarm bell, indicating the era in which China’s internet firms had the authority’s green light to grow at breakneck speed ended. The suspension came as the government made “major changes in the fintech regulatory environment,” which subsequently led to a restructuring at Ant and brought it under strict financial regulations.

Last year, a government investigation into Didi over its cross-border data sharing practice again underscored Beijing’s determination to tighten control over what it once deemed its “internet darlings.”

Smaller startups also feel the impact. Internet platforms of all sizes now face severe fines and even service suspension if they fail to institute the required content censorship and data storing mechanisms, which could easily cost up to several million yuan (1 USD = 6.4 yuan) a year for an early-stage, data-rich startup, two founders told us.

It isn’t just the compliance costs that are hobbling growth. The unpredictable nature of censorship — phrases or images that are tolerated one day can be deemed political and illegal the next — puts enormous pressure on young, cash-strapped companies to figure out the boundary of what is acceptable online.

“Venture capital firms in China, especially USD funds, didn’t use to care whether a startup made money or not in the beginning. As long as the company was seeing miraculous growth, it could take care of monetization later. But this formula has stopped working because any app can be taken down at any time,” said Lucas.

Tencent-backed Jike, a social network popular in the Chinese VC and startup community, was abruptly shuttered for a year before relaunching in 2020. The reason for its suspension was never disclosed, though many speculated it was due to censorship.

For many Chinese entrepreneurs, going public in the US, which has the world’s largest stock exchanges, is the ultimate goal, which would allow them to eventually cash out and generate more capital for scaling. But that route is also looking dimmer. In December, China’s cybersecurity regulator said internet platform operators with data of more than one million individuals [within China] must undergo a pre-IPO review before listing abroad. If the regulator decides the platform poses national security threats, the IPO will be stalled.

Around the same time, China’s securities authority proposed that a company, regardless of where it’s incorporated, must go through a filing process with the Chinese government if its main management mostly consists of Chinese nationals or executives who live in China, and whose main business operation is in China.

To help startups bypass potential restrictions over their pursuit of overseas listings, many VC firms in China are now advising their portfolio companies to pursue international markets instead. Some are even providing foreign citizenship applications for entrepreneurs as part of the post-investment service, we learned from a founder and an investor.

A startup’s success, Lucas lamented, now hinges partly on whether the founder can predict the direction of Chinese policies and follow them through. “We entrepreneurs shouldn’t be expected to be political scientists. We should be left alone to focus on building the product.”

Going to the sea

As the regulatory environment becomes increasingly stifling, young companies in China find it more difficult to emulate the success of their predecessors like Alibaba and Tencent, which started out two decades ago. Some have no choice but to abandon their China dreams. But on the bright side of things, consumer internet models that have proven successful in China, such as bike-sharing, virtual gifting, social commerce, and grocery delivery, also provide a useful playbook for the rest of the world.

“We believe that many Chinese pioneered or popularized technology-enabled business models are better suited for emerging markets, far more so than models coming in from the United States,” suggested Ben Harburg, managing partner at MSA Capital, which invests in global startups inspired by China’s tech industry.

“I think everyone would love to be some variation of Ant Group in terms of having money markets, loans, payments, merchant to peer, peer to peer [services],” the investor added. “Everything within the China mobile-first fintech ecosystem is very much an exemplar for the rest of the world.”

Chinese startups going global, or what’s called “chuhai”, literally “going to the sea,” have gone through several transformations over the past two decades. They went from exporting cheap electronics, creating a foreign version of something that is successful in China, like Tencent’s mobile game Honor of Kings, to building services and products that are devised to compete globally from day one.

“Companies in the past were globalizing based off of their successful model and examples in China, then taking the same product overseas,” observed Rilly Chen, who previously worked on Ant’s international investment team.

“Whereas now, we are seeing more companies who build their products for international customers at the get-go, but the infrastructure and engineering basis still rests in China.”

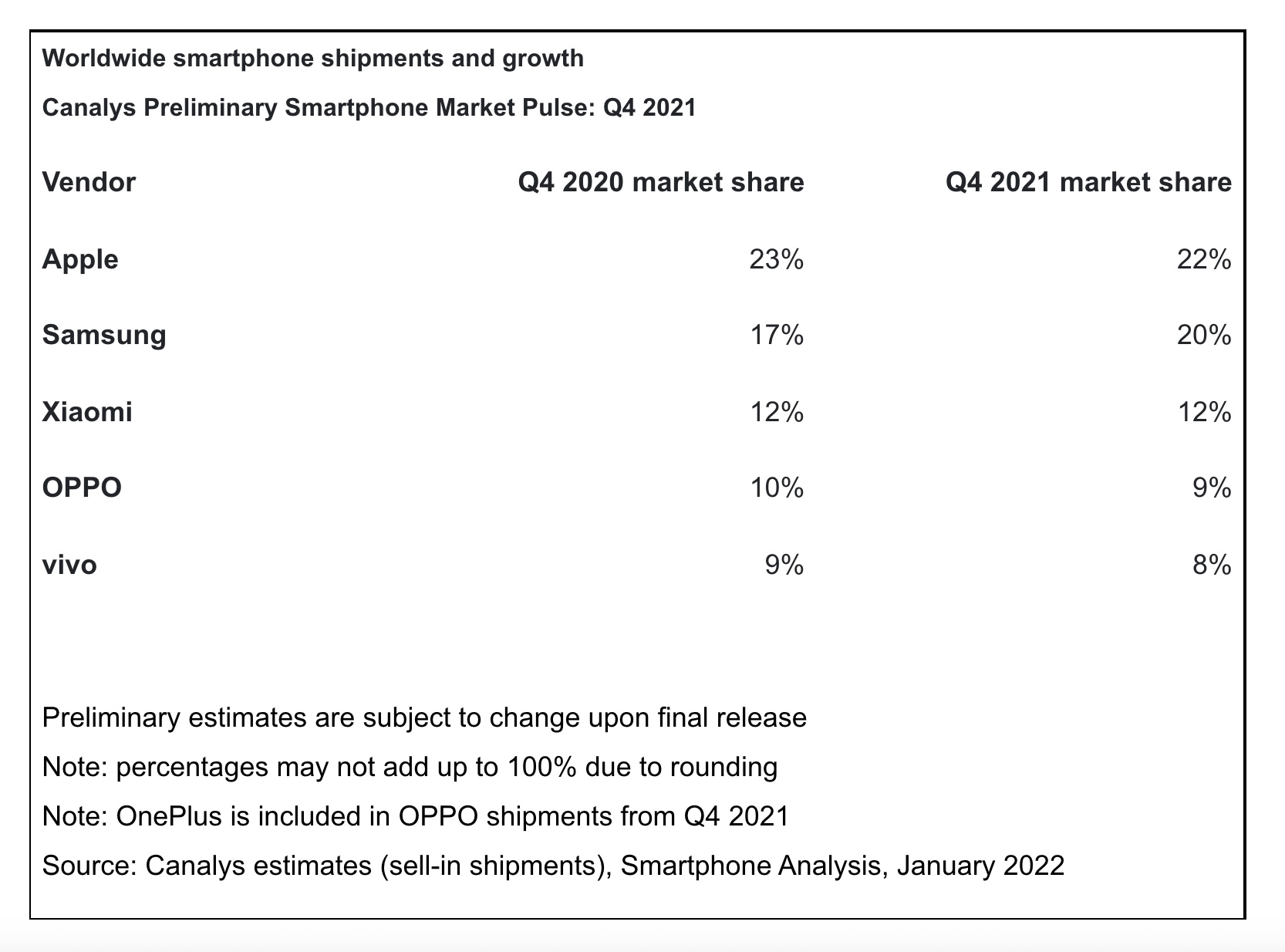

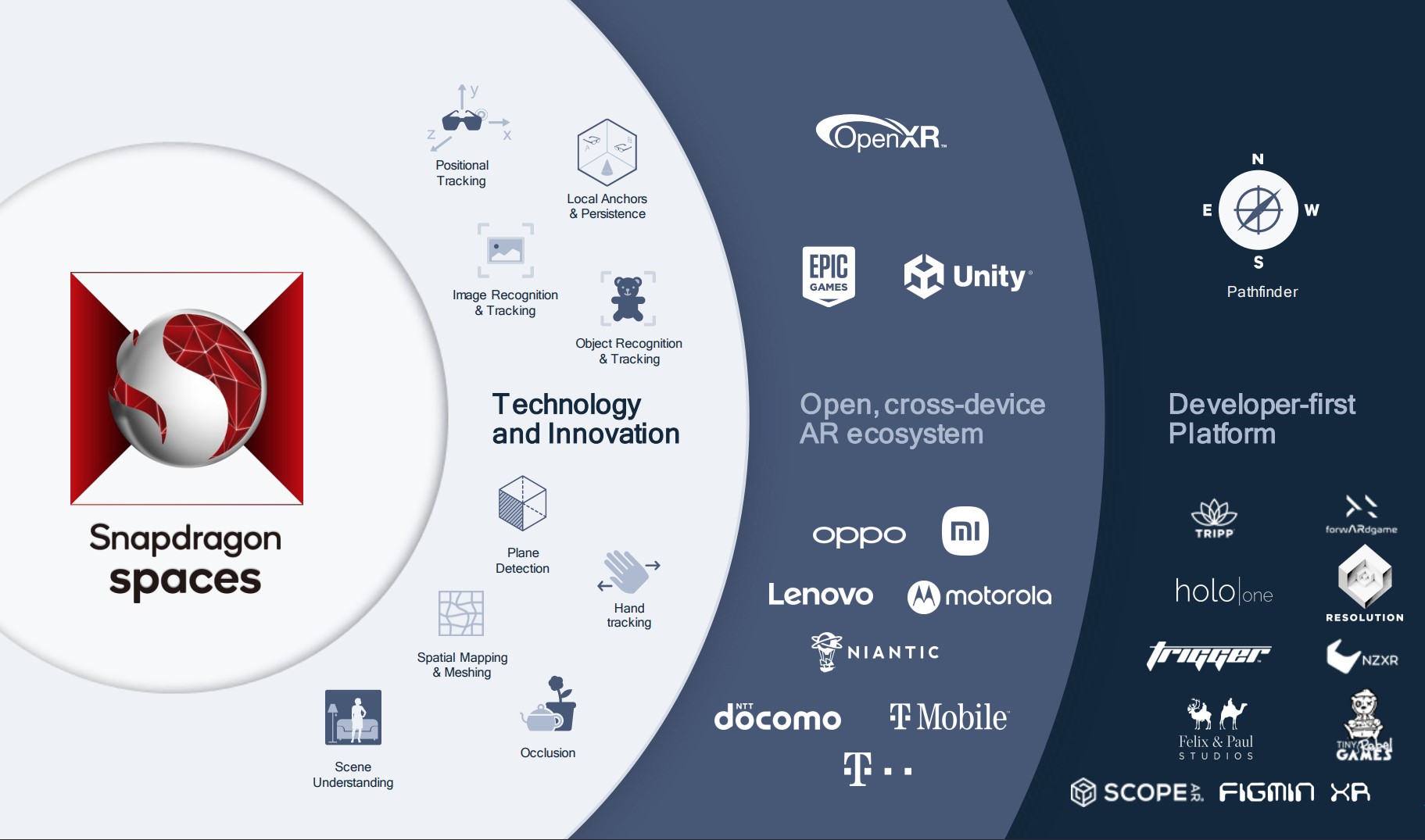

Smartphone makers Xiaomi and Oppo, and apps like selfie beautifier Meitu and TikTok are notable players of the earlier generations, whereas fast fashion upstart Shein exemplifies the latter category of companies that operate mostly out of China while serving international customers.

Going to the sea is no small feat. TikTok’s saga in the US, where the Trump administration intended to force a sale of the short video app, shows how a Chinese app with enormous global success can get caught up in geopolitical tensions. Stringent privacy rules in developed regions, like Europe’s GDPR, also pose new challenges to Chinese founders with little exposure to overseas compliance practices.

The current wave of Chinese startups going global tends to have Western-educated, bilingual founders born in the 1990s like Lucas. As they charge into new frontiers, they bring with them lessons from home, potentially helping to evangelize China’s tech business models and culture. At the same time, their home market is missing out on the service and creativity of these young, ambitious entrepreneurs driven away by the country’s regulatory storm.

“I think that [Chinese companies globalizing] is quite positive, but at the same time, I would also caveat with the fact that there is going to be potentially a brain drain in China, especially in sectors where Chinese entrepreneurs have found it difficult to navigate the blurred lines of regulation,” said Wise’s Chen.