Angel investing has traditionally been mostly open to men, who travel in certain circles and have access to certain networks, but Amanda Robson, a principal at Cowboy Ventures, is attempting to change that by building an informal network of women and non-binary folks who have the means to write checks, but for whatever reason have not been able to easily move into this type of investing.

Robson says that when it comes to angel investing, women and non-binary people have been left out. “I had a number of friends who had recently within the past couple of years become VP-level at different companies, and they had an interest in angel investing, and they had the means to at that point, but they didn’t have access,” she said.

That was in contrast to males in a similar position. “They found that a lot of their male counterparts who were also execs or male founders were getting pinged by their VC friends to join in on deals, and they weren’t getting the same treatment,” she said.

Robson says that she found this surprising at first because at her firm, they try to fill the cap table with a diverse set of angels. As she looked around, she found that wasn’t the case at all firms, but it wasn’t always because of a lack of desire to be more diverse. It was also a sourcing problem. They didn’t know where to look.

Amanda Robson, principal at Cowboy Ventures

So if you had one group looking to invest, and another looking for diverse investors, it seemed that something could be done to bridge the gap. “I just found myself in a unique position having been in venture for almost six years and having a bunch of VC relationships because of that, and then also having access to awesome female [and non-binary] founders and operators that I could kind of bridge that gap in a pretty seamless way,” she said.

Her experience is not uncommon. Diana Murakhovskaya, general partner and co-founder at the Houston-based Artemis Fund, told TechCrunch recently that prior to launching the fund in 2019, she and her co-founders attended networking events in the Houston area and noticed a dearth of women. She started hosting dinners to find out why.

“I said, ‘Where are all the women?’ [ … ] And so we started doing these dinners to bring together women and asking them why they’re not investing, what they’re doing. And these were all corporate women [who had the money to invest].” Like Robson, Murakhovskaya found that these women had never been invited to invest, and they started a firm to change that.

Robson took a different approach. She has a day job, but she knew that she could make some introductions when it made sense. “So I’m the conduit between the two [groups]. I have this database with angel investors and other VC relationships and then also deal flow that I see that will come from other angel syndicate groups or deals that Cowboy can’t invest in because we’re conflicted out, and I try to connect those two,” she said.

Robson, on her own, created this database of people, many of whom she knew previously or learned about when she put out a call for female and non-binary angel investors on Twitter. “I chatted with them and got a sense of their background and what they were interested in, if they truly understood the risks and dynamics of angel investing, and added folks that way.”

She said going outside her network would also help create a more diverse database that went beyond people she had known personally. “I also knew that my network would be limited, and the whole point of this is increasing access, so I wanted to be a little bit more public about it so folks who wanted to be angels could see those messages on Twitter and then join in,” she said.

The database includes the names, check sizes they are willing to invest, sectors they want to invest in and previous investments (if any). She says that typical check sizes are between $15,000 and $50K, but she has seen checks as small as $5K or less as she attempts to get more people involved.

“In some cases recently there have been newer female [and] non-binary angel investors who have wanted to write checks that are $5K, some even below, and some founders and VCs have been open to those smaller check amounts because they want to add diversity to the cap table,” she said.

Lisa Wallace, who is co-founder at pay equity startup Assemble, says that she had been an angel for a couple of years when she responded to one of Robson’s tweets. She also found that when her company was raising a seed round, it was difficult to find a diverse group of angels for her cap table. She says that Robson’s network solves both problems.

“I think that there’s actually two parts of the problem. First of all, I’m a diverse angel, and I want to make sure that I [can access] dealflow, selfishly. But on the other side of it, it would have been really easy had Amanda had this when I was raising my round because I would have just pinged her,” Wallace said.

Stella Garber is another angel in Robson’s network who is former CMO at Trello, and started angel investing in 2016. She too came across one of Robson’s tweets and says that it’s always good to find other sources of possible deals as an angel investor.

“It’s really great to see all the different types of deals that come through that channel. There’s been a mix of all types of different industries, mostly early stage I would say. But obviously as an angel, you have to do your own due diligence, but it’s just nice to have that channel to get deals from,” Garber said.

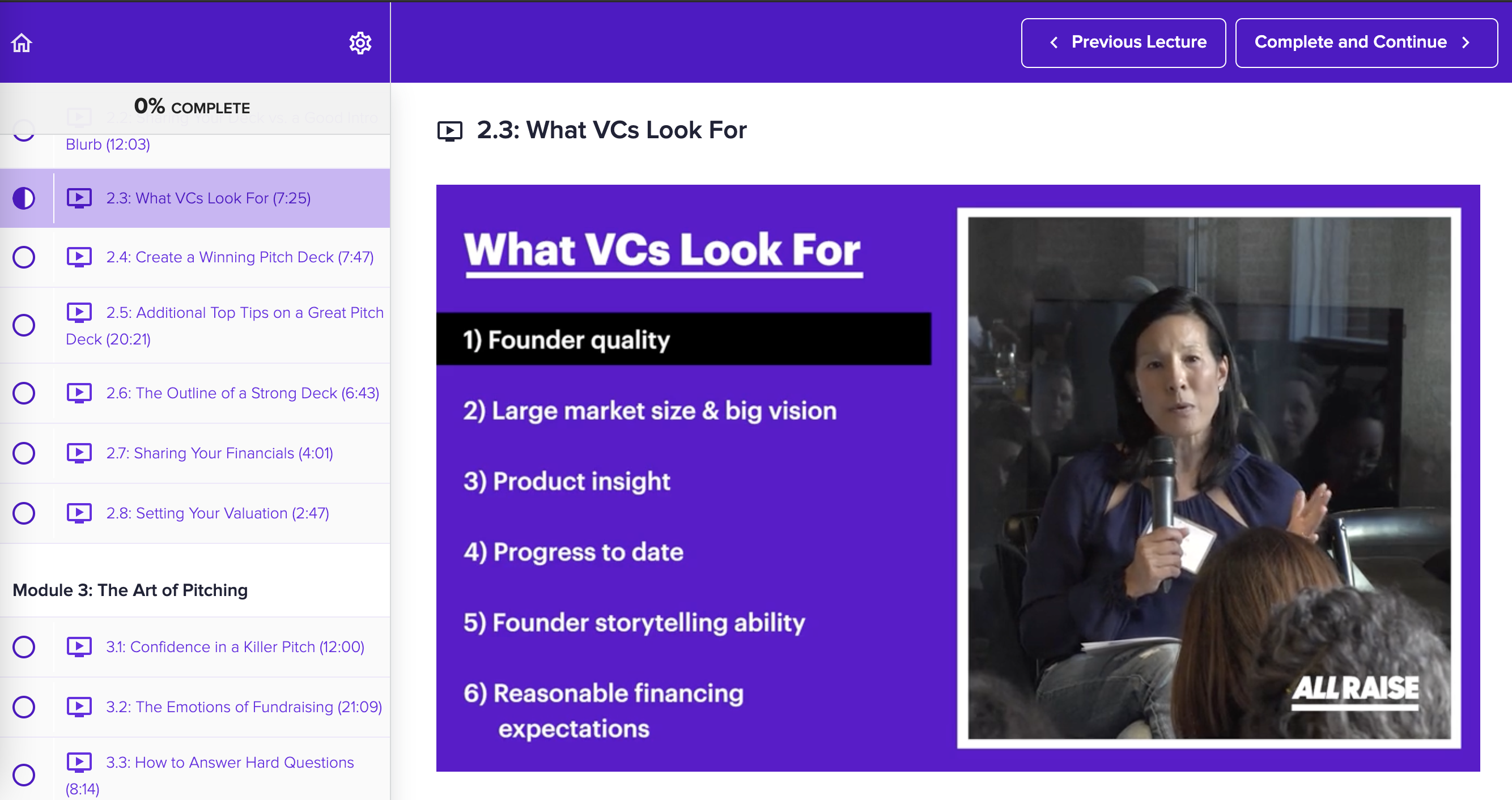

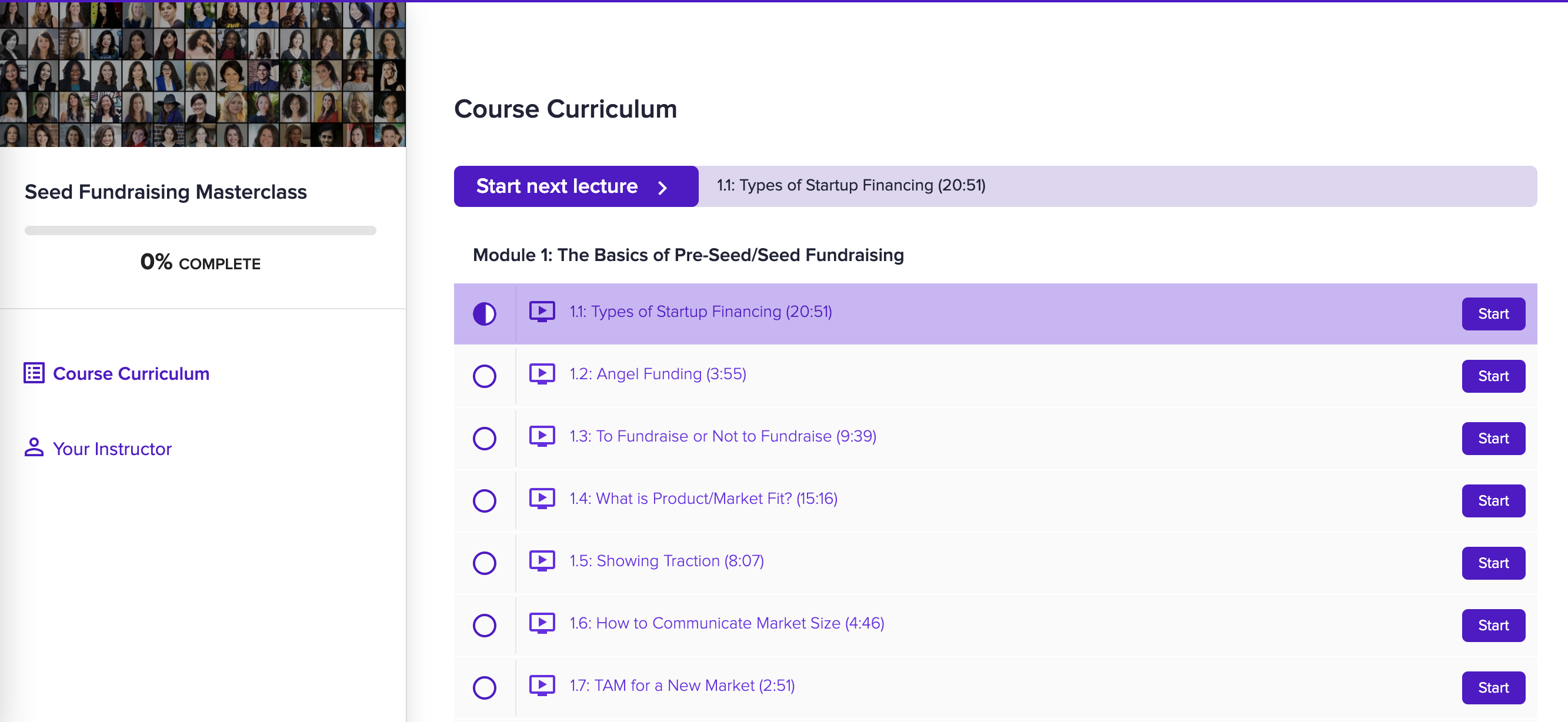

While these two had experience in angel investing, not everyone does, so Robson has also been helping set up workshops to explain what’s involved to those who are expressing interest and want to learn the mechanics of this type of investing.

Robson admits that quite a bit overhead is required to run the network because she is the sole conduit. But she says that it’s the kind of job that is hard to outsource because she has the first-hand knowledge of both firms and angels that the role requires.

“I do want to get some help to grow it, but I also think that there are limits to how much I can outsource any parts of this because the access piece is super important. I’ve been doing this for four to five months and I’ve only sent 18 deals through, but all of those ended up getting a lot of interest from the group because they’re highly curated.”

She says the ultimate purpose is to build this network of successful angels. “I want to have these rockstar angels who’ve gotten access to amazing deals and have amazing track records. And so that’s really the ultimate goal. And it’s more about that and in making these angels successful than me leading this group.”

There are now 50+ female & non-binary angel investors in our database

There are now 50+ female & non-binary angel investors in our database to your deals!

to your deals! group for our Angel Investing 101 session with

group for our Angel Investing 101 session with