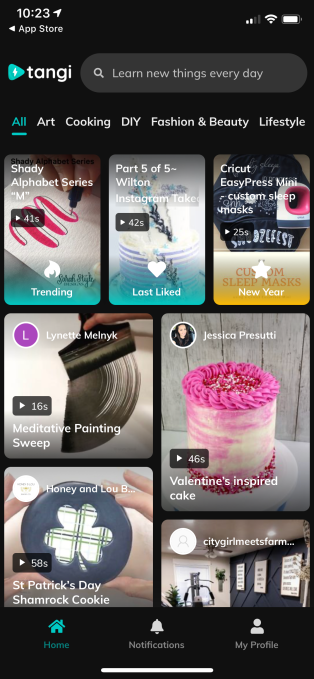

The latest project to emerge from Google’s in-house incubator, Area 120, takes the newfound interest in short-form video and focuses it on the DIY space. The company today is launching a short video platform called Tangi, initially on the web and iOS, that allows creative types to share how-to videos on subjects like crafting, painting, cooking, fashion, beauty and more.

Unlike apps like TikTok or newly-launched Byte, which are more focused on entertainment, Tangi aims to help people learn.

“We only focus on DIY and creativity content,” explains Tangi founder, Coco Mao. “Our platform’s goal is to help people learn to craft, cook, and create with quick one-minute videos. We designed Tangi to make it easier for users to find a lot of high-quality how-to videos,” she says.

Mao was inspired to create Tangi after going home to visit her parents in Shanghai. She found they were watching a lot of how-to videos on painting and photography on their phone, even though she had always believed they were “smartphone challenged.”

“My mom has always had a creative side, and I was surprised to learn that she’s now an amateur oil painter thanks to these niche communities with quick how-to videos,” Mao says. “I, too, joined some of these vibrant creative communities that make videos around cooking and fashion. I noticed something magical in these videos: They could quickly get a point across—something that used to take a long time to learn with just text and images,” she notes.

While Tangi’s vertical videos can be up to one-minute long, most average around 45 seconds. That means it’s not necessarily the place to be walked step-by-step through a complicated recipe as you could be on YouTube, for example. Instead, the videos might show you a quick cooking trick or inspire you to try a new idea in the kitchen.

Another difference between Tangi and other short-form video apps is a feature it includes called “Try It.” This encourages users to upload photos of their re-creation of the video as a way to interact with other community members, says Mao.

Another difference between Tangi and other short-form video apps is a feature it includes called “Try It.” This encourages users to upload photos of their re-creation of the video as a way to interact with other community members, says Mao.

For example, one of the most re-created videos is this one of making guacamole in the avocado shell.

The creator might leave an actual recipe in the comments, however, even if they don’t show you each individual step in detail. (And it’s arguably a lot easier to follow a recipe on Tangi than on most of today’s recipe sites which are overrun with ads and SEO-driven “personal stories.”)

Already, Tangi is being used by a number of creators including DIY and lifestyle blogger Holly Grace, portrait artist Rachel Faye Carter, baker and food creator Paola D Yee, beauty vlogger Sew Wigged Out, art and DIYer TheArtGe, cooking and DIYer JonathanBlogs, and others.

Also unlike other social video apps, uploading to Tangi isn’t currently open to all. Instead, creators need to apply to be a part of the video platform. This allows Tangi to ensure their videos remain focused on creativity and DIY activities.

As a viewer, you can search Tangi for whatever it is you want to learn or filter videos by category, like art, cooking, DIY, fashion & beauty, and lifestyle. Or you can simply scroll down the home page until something catches your interest. To save a video or show your support for the creator, you click the heart icon to like the video. This saves it to your “Liked” section under your profile.

Tangi ends up having a sort of Pinterest-y vibe due to its content.

At launch, Tangi is available everywhere except the E.U., initially on the web and on iOS. The app is a free download, is ad-free, and isn’t currently being monetized in other ways.