A fleet of electric, autonomous Hyundai Kona crossovers — equipped with a self-driving system from Chinese autonomous startup Pony .ai and Via’s ride-hailing platform, will start shuttling customers on public roads next week.

The robotaxi service called BotRide will operate on public roads in Irvine, California, beginning November 4. This isn’t a driverless service; there will be a human safety driver behind the wheel at all times. But it is one of the few ride-hailing pilots on California roads. Only four companies, AutoX, Pony.ai, Waymo and Zoox have permission to operate a ride-hailing service using autonomous vehicles in the state of the California.

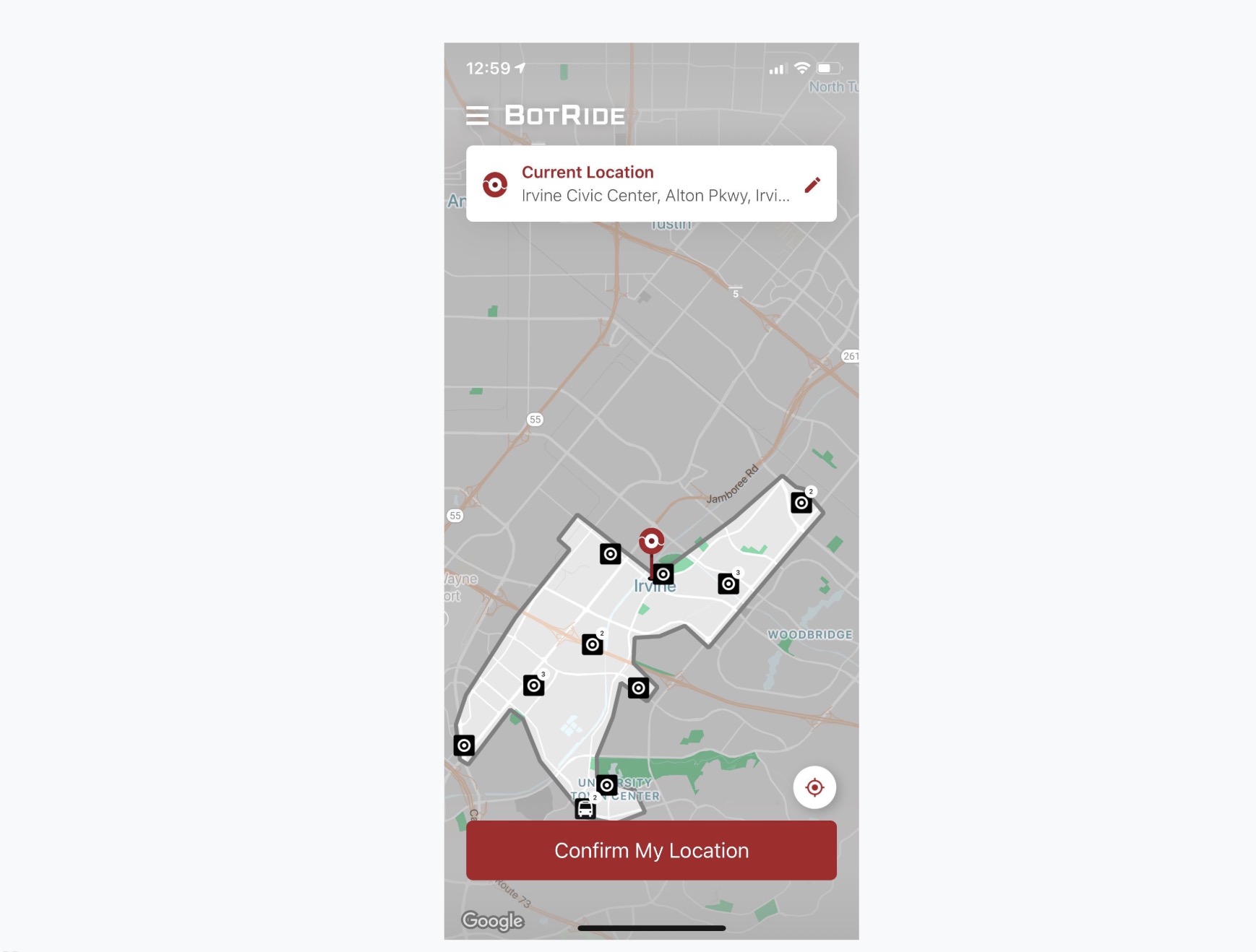

Customers will be able to order rides through a smartphone app, which will direct passengers to nearby stops for pick up and drop off. Via’s expertise is on shared rides, and this platform aims for the same multiple rider goal. Via’s platform handles the on-demand ride-hailing features such as booking, passenger and vehicle assignment and vehicle identification (QR code). Via has two sides to its business. The company operates consumer-facing shuttles in Chicago, Washington, D.C. and New York. It also partners with cities and transportation authorities — and now automakers launching robotaxi services — giving clients access to their platform to deploy their own shuttles.

Hyundai said BotRide is “validating its user experience in preparation for a fully driverless future.” Hyundai didn’t explain when this driverless future might arrive. Whatever this driverless future ends up looking like, Hyundai sees this pilot as a critical marker along the way.

Hyundai said it is using BotRide to study consumer behavior in an autonomous ride-sharing environment, according to Christopher Chang, head of business development, strategy and technology division, Hyundai Motor Company .

“The BotRide pilot represents an important step in the deployment and eventual commercialization of a growing new mobility business,” said Daniel Han, manager, Advanced Product Strategy, Hyundai Motor America.

Hyundai might be the household name behind BotRide, but Pony.ai and Via are doing much of the heavy lifting. Pony.ai is a relative newcomer to the AV world, but it has already raised $300 million on a $1.7 billion valuation and locked in partnerships with Toyota and Hyundai.

The company, which has operations in China and California and about 500 employees globally, was founded in late 2016 with backing from Sequoia Capital China, IDG Capital and Legend Capital.

It’s also one of the few autonomous vehicle companies to have both a permit with the California Department of Motor Vehicles to test AVs on public roads and permission from the California Public Utilities Commission to use these vehicles in a ride-hailing service. Under rules established by the CPUC, Pony.ai cannot charge for rides.