A report by the UK’s Electoral Commission has called for urgent changes in the law to increase transparency about how digital tools are being used for political campaigning, warning that an atmosphere of mistrust is threatening the democratic process.

The oversight body, which also regulates campaign spending, has spent the past year examining how digital campaigning was used in the UK’s 2016 EU referendum and 2017 general election — as well as researching public opinion to get voters’ views on digital campaigning issues.

Among the changes the Commission wants to see is greater clarity around election spending to try to prevent foreign entities pouring money into domestic campaigns, and beefed up financial regulations including bigger penalties for breaking election spending rules.

It also has an ongoing investigation into whether pro-Brexit campaigns — including the official Vote Leave campaign — broke spending rules. And last week the BBC reported on a leaked draft of the report suggesting the Commission will find the campaigns broke the law.

Last month the Leave.EU Brexit campaign was also fined £70,000 after a Commission investigation found it had breached multiple counts of electoral law during the referendum.

Given the far larger sums now routinely being spent on elections — another pro-Brexit group, Vote Leave, had a £7M spending limit (though it has also been accused of exceeding that) — it’s clear the Commission needs far larger teeth if it’s to have any hope of enforcing the law.

Digital tools have lowered the barrier of entry for election fiddling, while also helping to ramp up democratic participation.

“On digital campaigning, our starting point is that elections depend on participation, which is why we welcome the positive value of online communications. New ways of reaching voters are good for everyone, and we must be careful not to undermine free speech in our search to protect voters. But we also fully recognise the worries of many, the atmosphere of mistrust which is being created, and the urgent need for action to tackle this,” writes commission chair John Holmes.

“Funding of online campaigning is already covered by the laws on election spending and donations. But the laws need to ensure more clarity about who is spending what, and where and how, and bigger sanctions for those who break the rules.

“This report is therefore a call to action for the UK’s governments and parliaments to change the rules to make it easier for voters to know who is targeting them online, and to make unacceptable behaviour harder. The public opinion research we publish alongside this report demonstrates the level of concern and confusion amongst voters and the will for new action.”

The Commission’s key recommendations are:

- Each of the UK’s governments and legislatures should change the law so that digital material must have an imprint saying who is behind the campaign and who created it

- Each of the UK’s governments and legislatures should amend the rules for reporting spending. They should make campaigners sub-divide their spending returns into different types of spending. These categories should give more information about the money spent on digital campaigns

- Campaigners should be required to provide more detailed and meaningful invoices from their digital suppliers to improve transparency

- Social media companies should work with us to improve their policies on campaign material and advertising for elections and referendums in the UK

- UK election and referendum adverts on social media platforms should be labelled to make the source clear. Their online databases of political adverts should follow the UK’s rules for elections and referendums

- Each of the UK’s governments and legislatures should clarify that spending on election or referendum campaigns by foreign organisations or individuals is not allowed. They would need to consider how it could be enforced and the impact on free speech

- We will make proposals to campaigners and each of the UK’s governments about how to improve the rules and deadlines for reporting spending. We want information to be available to voters and us more quickly after a campaign, or during

- Each of the UK’s governments and legislatures should increase the maximum fine we can sanction campaigners for breaking the rules, and strengthen our powers to obtain information outside of an investigation

The recommendations follow revelations by Chris Wylie, the Cambridge Analytica whistleblower (pictured at the top of this post) — who has detailed to journalists and regulators how Facebook users’ personal data was obtained and passed to the now defunct political consultancy for political campaigning activity without people’s knowledge or consent.

In addition to the Cambridge Analytica data misuse scandal, Facebook has also been rocked by earlier revelations of how extensively Kremlin-backed agents used its ad targeting tools to try to sew social division at scale — including targeting the 2016 US presidential election.

The Facebook founder, Mark Zuckerberg, has since been called before US and EU lawmakers to answer questions about how his platform operates and the risks it’s posing to democratic processes.

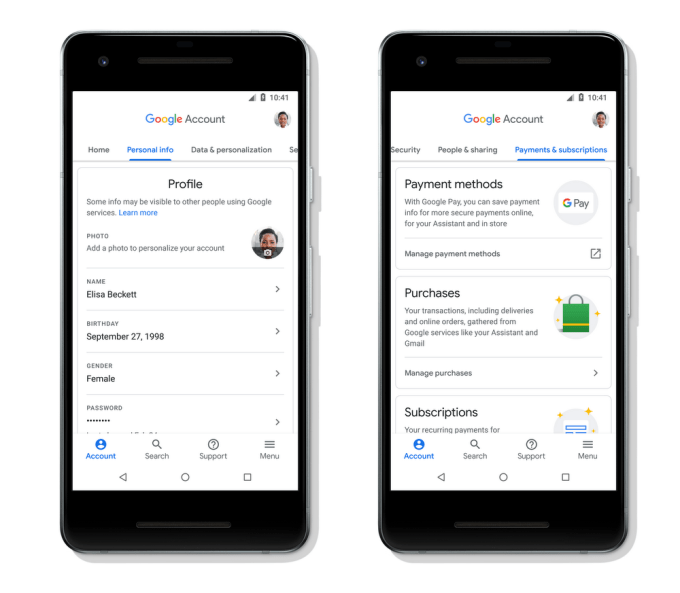

The company has announced a series of changes intended to make it more difficult for third parties to obtain user data, and to increase transparency around political advertising — adding a requirement for such ads to continue details of how has paid for them, for example, and also offering a searchable archive.

Although critics question whether the company is going far enough — asking, for example, how it intends to determine what is and is not a political advert.

Facebook is not offering a searchable archive for all ads on its platform, for example.

Zuckerberg has also been accused of equivocating in the face of lawmakers’ concerns, with politicians on both sides of the Atlantic calling him out for providing evasive, misleading or intentionally obfuscating responses to concerns and questions around how his platform operates.

The Electoral Commission makes a direct call for social media firms to do more to increase transparency around digital political advertising and remove messages which “do not meet the right standards”.

“If this turns out to be insufficient, the UK’s governments and parliaments should be ready to consider direct regulation,” it also warns.

We’ve reached out to Facebook comment and will update this post with any response.

A Cabinet Office spokeswoman told us it would send the government response to the Electoral Commission report shortly — so we’ll also update this post when we have that.

The UK’s data protection watchdog, the ICO, has an ongoing investigating into the use of social media data for political campaigning — and commissioner Elizabeth Denham recently made a call for stronger disclosure rules around political ads and a code of conduct for social media firms. The body is expected to publish the results of its long-running investigation shortly.

At the same time, a DCMS committee has been running an inquiry into the impact of fake news and disinformation online, including examining the impact on the political process. Though Zuckerberg has declined its requests for him to personally testify — sending a number of minions in his place, including CTO Mike Schroepfer who was grilled for around five hours by irate MPs and his answers still left them dissatisfied.

The committee will set out the results of this inquiry in another report touching on the impact of big tech on democratic processes — likely in the coming months. Committee chair Damian Collins tweeted today to say the inquiry has “also highlighted how out of date our election laws are in a world increasingly dominated by big tech media”.

On its forthcoming Brexit campaign spending report, an Electoral Commission spokesperson told us: “In accordance with its Enforcement Policy, the Electoral Commission has written to Vote Leave, Mr Darren Grimes and Veterans for Britain to advise each campaigner of the outcome of the investigation announced on 20 November 2017. The campaigners have 28 days to make representations before final decisions are taken. The Commission will announce the outcome of the investigation and publish an investigation report once this final decision has been taken.”