The UK has this week started testing a coronavirus contacts tracing app which NHSX, a digital arm of the country’s National Health Service, has been planning and developing since early March. The test is taking place in the Isle of Wight, a 380km2 island off the south coast of England, with a population of around 140,000.

The NHS COVID-19 app uses Bluetooth Low Energy handshakes to register proximity events (aka ‘contacts’) between smartphone users, with factors such as the duration of the ‘contact event’ and the distance between the devices feeding an NHS clinical algorithm that’s being designed to estimate infection risk and trigger notifications if a user subsequently experiences COVID-19 symptoms.

The government is promoting the app as an essential component of its response to fighting the coronavirus — the health minister’s new mantra being: ‘Protect the NHS, stay home, download the app’ — and the NHSX has said it expects the app to be “technically” ready to deploy two to three weeks after this week’s trial.

However there are major questions over how effective the tool will prove to be, especially given the government’s decision to ‘go it alone’ on the design of its digital contacts tracing system — which raises some specific technical challenges linked to how modern smartphone platforms operate, as well as around international interoperability with other national apps targeting the same purpose.

In addition, the UK app allows users to self report symptoms of COVID-19 — which could lead to many false alerts being generated. That in turn might trigger notification fatigue and/or encourage users to ignore alerts if the ratio of false alarms exceeds genuine alerts.

Keep calm and download the app?

How users will generally respond to this technology is a major unknown. Yet mainstream adoption will be needed to maximize utility; not just one-time downloads. Dealing with the coronavirus will be a marathon not a sprint — which means sustaining usage will be vital to the app functioning as intended. And that will require users to trust that the app is both useful for the claimed public health purpose, by being effective at shrinking infection risk, and also that using it will not create any kind of disadvantages for them personally or for their friends and family.

The NHSX has said it will publish the code for the app, the DPIA (data protection impact assessment) and the privacy and security models — all of which sounds great, though we’re still waiting to see those key details. Publishing all that before the app launches would clearly be a boon to user trust.

A separate consideration is whether there should be a dedicated legislation wrapper put around the app to ensure clear and firm legal bounds on its use (and to prevent abuse and data misuse).

As it stands the NHS COVID-19 app is being accelerated towards release without this — relying on existing legislative frameworks (with some potential conflicts); and with no specific oversight body to handle any complaints. That too could impact user trust.

The overarching idea behind digital contacts tracing is to leverage uptake of smartphone technology to automate some contacts tracing, with the advantage that such a tool might be able to register fleeting contacts, such as between strangers on the street or public transport, that may more difficult for manual contacts tracing methods to identify. Though whether these sorts of fleeting contacts create a significant risk of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus has not yet been quantified.

All experts are crystal clear on one thing: Digital contacts tracing is only going to be — at very best — a supplement to manual contact tracing. People who do not own or carry smartphones or who do not or cannot use the app obviously won’t register in any captured data. Technical issues may also create barriers and data gaps. It’s certainly not a magic bullet — and may, in the end, turn out to be ill-suited for this use case (we’ve written a general primer on digital contacts tracing here).

One major component of the UK approach is that it’s opted to create a so-called ‘centralized’ system for coronavirus contacts tracing — which leads to a number of specific challenges.

While the NHS COVID-19 app stores contacts events on the user’s device initially, at the point when (or if) a user chooses to report themselves having coronavirus symptoms then all their contacts events data is uploaded to a central server. This means it’s not just a user’s own identifier but a list of any identifiers they have encountered over the past 28 days — so, essentially, a graph of their recent social interactions.

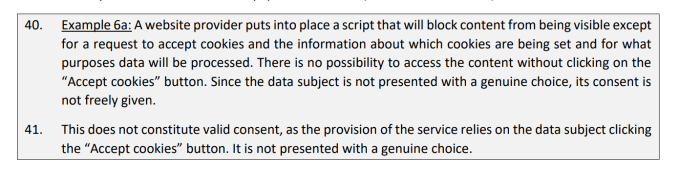

This data cannot be deleted after the fact, according to the NHSX, which has also said it may be used for “research” purposes related to public health — raising further questions around privacy and trust.

Questions around the legal bases for this centralized approach also remain to be answered in detail by the government. UK and EU data protection law emphasize data minimization as a key principle; and while there’s flexibility built into these frameworks for a public health emergency there is still a requirement on the government to detail and justify key data processing decisions.

The UK’s decision to centralize contacts data has another obvious and immediate consequence: It means the NHS COVID-19 app will not be able to plug into an API that’s being jointly developed by Apple and Google to provide technical support for Bluetooth-based national contacts tracing apps — and due to be release this month.

The tech giants have elected to support decentralized app architectures for these apps — which, conversely, do not centralize social graph data. Instead, infection risk calculations are performed locally on the device.

By design, these approaches avoid providing a central authority with information on who infected whom.

In the decentralized scenario, an infected user consents to their ephemeral identifier being shared with other users so apps can do matching locally, on the end-user device — meaning exposure notifications are generated without a central authority needing to be in the loop. (It’s also worth noting there are ways for decentralized protocols to feed aggregated contact data back to a central authority for epidemiological research, though the design is intended to prevent users’ social graph being exposed. A system of ‘exposure notification’, as Apple and Google are now branding it, has no need for such data, is their key argument. The NHSX counters that by suggesting social graph data could provide useful epidemiological insights — such as around how the virus is being spread.)

At the point a user of the NHS COVID-19 app experiences symptoms or gets a formal coronavirus diagnosis — and chooses to inform the authorities — the app will upload their recent contacts to a central server where infection risk calculations are performed.

The system will then send exposure notifications to other devices — in instances where the software deems there may be at risk of infection. Users might, for example, be asked to self isolate to see if they develop symptoms after coming into contact with an infected person, or told to seek a test to determine if they have COVID-19 or not.

A key detail here is that users of the NHS COVID-19 app are assigned a fixed identifier — basically a large, random number — which the government calls an “installation ID”. It claims this identifier is ‘anonymous’. However this is where political spin in service of encouraging public uptake of the app is being allowed to obscure a very different legal reality: A fixed identifier linked to a device is in fact pseudonymous data, which remains personal data under UK and EU law. Because, while the user’s identity has been ‘obscured’, there’s still a clear risk of re-identification.

Truly ‘anonymous’ data is a very high bar to achieve when you’re dealing with large data-sets. In the NHS COVID-19 app case there’s no reason beyond spin for the government to claim the data is “anonymous”; given the system design involves a device-linked fixed identifier that’s uploaded to a central authority alongside at least some geographical data (a partial postcode: which the app also asks users to input — so “the NHS can plan your local NHS response”, per the official explainer).

The NHSX has also said future versions of the app may ask users to share even more personal data, including their location. (And location data-sets are notoriously difficult to defend against re-identification.)

Nonetheless the government has maintained that individual users of the app will not be identified. But under such a system architecture this assertion sums to ‘trust us with your data’; the technology itself has not been designed to remove the need for individual users to trust a central authority, as is the case with bona fide decentralized protocols.

This is why Apple and Google are opting to support the latter approach — it cuts the internationally thorny issue of ‘government trust’ out of their equation.

However it also means governments that do want to centralize data face a technical headache to get their apps to function smoothly on the only two smartphone platforms that matter.

Technical and geopolitical headaches

The specific technical issue here relates to how these mainstream platforms manage background access to Bluetooth.

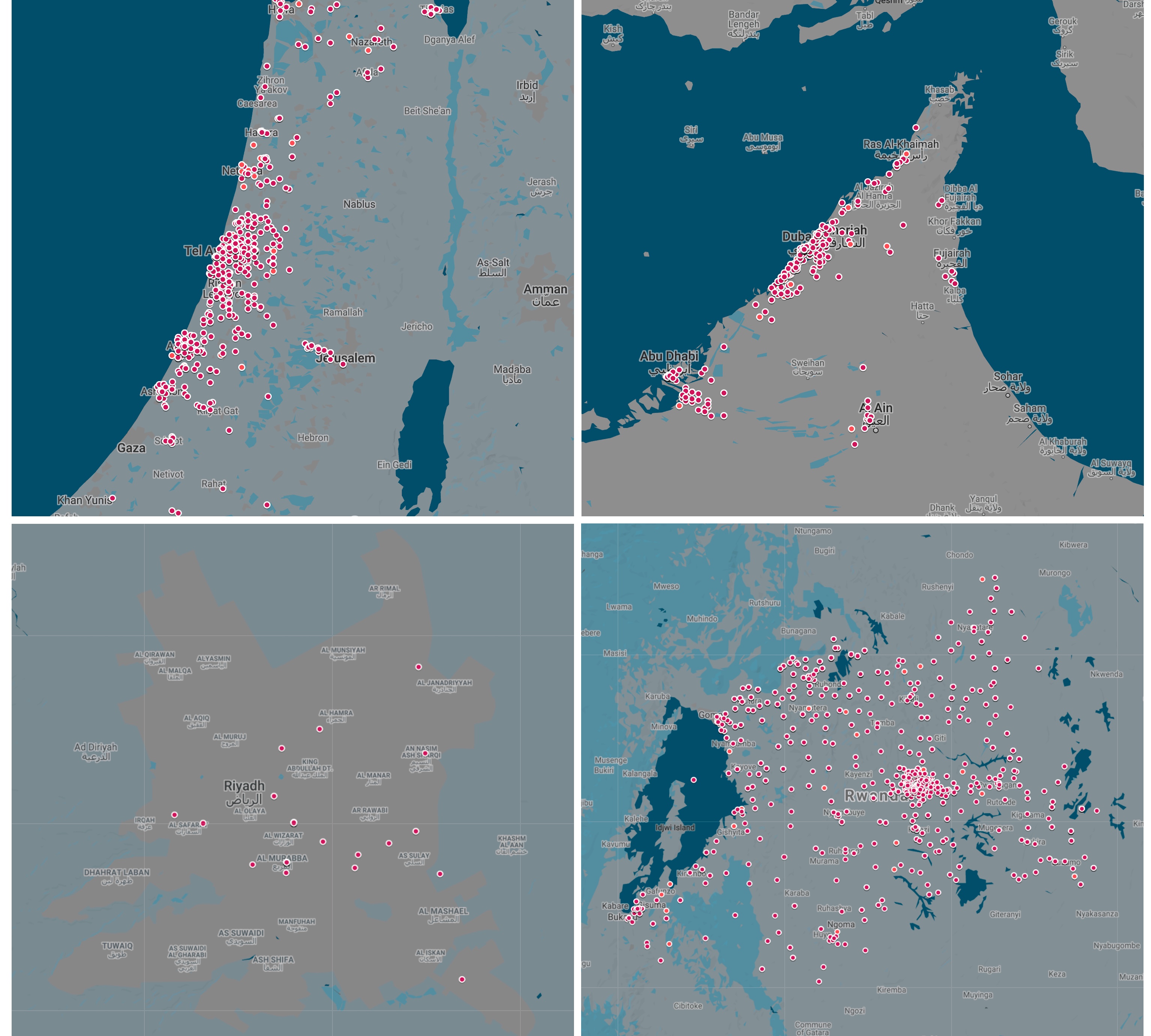

Using Bluetooth as a proxy for measuring coronavirus infection risk is of course a very new and novel technology. Singapore was reported to be the first country to attempt this. Its TraceTogether app, which launched in March, reportedly gained only limited (<20%) uptake — with technical issues on iOS being at least partly blamed for the low uptake.

The problem that the TraceTogether app faced initially is the software needed to be actively running and the iPhone open (not locked) for the tracing function to work. That obviously interferes with the normal multitasking of the average iPhone user — discouraging usage of the app.

It’s worth emphasizing that the UK is doing things a bit differently vs Singapore, though, in that it’s using Bluetooth handshakes rather than a Bluetooth advertising channel to power the contacts logging.

The NHS COVID-19 app has been designed to listen passively for other Bluetooth devices and then wake up in order to perform the handshake. This is intended as a workaround for these platform limits on background Bluetooth access. However it is still a workaround — and there are ongoing questions over how robustly it will perform in practice.

An analysis by The Register suggests the app will face a fresh set of issues in that iPhones specifically will fail to wake each other up to perform the handshakes — unless there’s also an Android device in the vicinity. If correct, it could result in big gaps in the tracing data (around 40% of UK smartphones run iOS vs 60% running Android).

Battery drain may also resurface as an issue with the UK system, though the NHSX has claimed its workaround solves this. (Though it’s not clear if they’ve tested what happens if an iPhone user switches on a battery saving mode which limits background app activity, for example.)

Other Bluetooth-based contract tracing apps that have tried to workaround platforms limits have also faced issues with interference related to other Bluetooth devices — such as Australia’s recently launched app. So there are a number of potential issues that could trouble performance.

Being outside the Apple-Google API also certainly means the UK app is at the mercy of future platform updates which could derail the specific workaround. Best laid plans that don’t involve using an official interface as your plug are inevitably operating on shaky ground.

Finally, there’s a huge and complex issue that’s essentially being glossed over by government right now: Interoperability with other national apps.

How will the UK app work across borders? What happens when Brits start travelling again? With no obvious route for centralized vs decentralized systems to interface and play nice with each other there’s a major question mark over what happens when UK citizens want to travel to countries with decentralized systems (or indeed vice versa). Mandatory quarantines because the government picked a less interoperable app architecture? Let’s hope not.

Notably, the Republic of Ireland has opted for a decentralized approach for its national app, whereas Northern Ireland, which is part of the UK but shares a land border with the Republic, will — baring any NHSX flip — be saddled with a centralized and thus opposing choice. It’s the Brexit schism all over again in app form.

Earlier this week the NHSX was asked about this cross-border issue by a UK parliamentary committee — and admitted it creates a challenge “we’ll have to work through”, though it did not suggest how it proposes to do that.

And while that’s a very pressing backyard challenge, the same interoperability gremlins arise across the English Channel — where a number of European countries are opting for decentralized apps, including Estonia, Germany and Switzerland. While Apple and Google’s choice at the platform level means future US apps may also be encouraged down a decentralized route. (The two US tech giants are demonstrably flexing their market power to press on and influence governments app design choices internationally.)

So countries that fix on a ‘DIY’ approach for the digital component of their domestic pandemic response may find it leads to some unwelcome isolation for their citizens at the international level.