Away from the limelight of the press and the frenzy of fundraising, a tech startup in India has achieved a feat that few of its peers have managed: going public.

IndiaMART, the country’s largest online platform for selling products directly to businesses, raised nearly $70 million in a rare tech IPO for India this week.

The milestone for the 23-year-old firm is so uncommon for India’s otherwise burgeoning startup ecosystem that, beyond being over-subscribed 36 times, pent up demand for IndiaMART’s stock saw its share price pop 40% on its first day of trading on National Stock Exchange on Thursday — a momentum that it sustained on Friday.

The stock ended Friday at Rs 1326 ($19.3), compared to its issue price of Rs 973 ($14.2).

IndiaMART is the first business-to-business e-commerce firm to go public in India. Its IPO also marks the first listing for a firm following the May reelection of Narendra Modi as the nation’s Prime Minister and the months-long drought that led to it.

Accounting firm EY said it expects more companies from India to follow suit and file for IPO in the coming months.

“Now that national elections are over and favorable results secured, IPO activity is expected to gain momentum in H2 2019 (second half of the year). Companies that had filed their offer documents with the Indian stock markets regulator during H2 2018 and Q1 2019 may finally come to market in the months ahead,” it said in a statement (PDF).

IndiaMART’s origin

The fireworks of the IPO are just as impressive as IndiaMART’s journey.

The startup was founded in 1996 and for the first 13 years, it focused on exports to customers abroad, but it has since modernized its business following the wave of the internet.

“The thesis was, in 1996, there were no computers or internet in India. The information about India’s market to the West was very limited,” Dinesh Agarwal, co-founder and CEO of IndiaMART, told TechCrunch in an interview.

Until 2008, IndiaMART was fully bootstrapped and profitable with $10 million in revenue, Agarwal said. But things started to dramatically change in that year.

“The Indian rupee became very strong against the dollar, which dwindled the exports business. This is also when the stock market was collapsing in the West, which further hurt the exports demand,” he explained.

Dinesh Agarwal, founder and CEO of IndiaMart.com, poses for a profile shot on July 29, 2015 in Noida, India.

By this time, millions of people in India were on the internet and, with tens of millions of people owning a feature phone, the conditions of the market had begun to shift towards digital.

“This is when we decided to pursue a completely different path. We started to focus on the domestic market,” Agarwal said.

Over the last 10 years, IndiaMART has become the largest e-commerce platform for businesses with about 60% market share, according to research firm KPMG. It handles 97,000 product categories — ranging from machine parts, medical equipment and textile products to cranes — and has amassed 83 million buyers and 5.5 million suppliers from thousands of towns and cities of India.

According to the most recent data published by the Indian government, there are about 50 to 60 million small and medium-sized businesses in India, but only around 10 million of them have any presence on the web. Some 97% of the top 50 companies listed on National Stock Exchange use IndiaMART’s services, Agarwal said.

That’s not to say that the transition to the current day was a straightforward process for the company. IndiaMART tried to capitalize on its early mover advantage with a stream of new services which ultimately didn’t reap the desired rewards.

In 2002, it launched a travel portal for businesses. A year later, it launched a business verification service. It also unveiled a payments platform called ABCPayments. None of these services worked and the firm quickly moved on.

Part of IndiaMART’s success story is its firm leadership and how cautiously it has raised and spent its money, Rajesh Sawhney, a serial angel investor who sits on IndiaMART’s board, told TechCrunch in an interview.

IndiaMART, which employs about 4,000 people, is operationally profitable as of the financial year that ended in March this year. It clocked some $82 million in revenue in the year. It has raised about $32 million to date from Intel Capital, Amadeus Capital Partners and Quona Capital. (Notably, Agarwal said that he rejected offers from VCs for a very long time.)

The firm makes most of its revenue from subscriptions it sells to sellers. A subscription gives a seller a range of benefits including getting featured on storefronts.

Where the industry stands

There are only a handful of internet companies in India that have gone public in the last decade. Online travel service MakeMyTrip went public in 2010. Software firm Intellect Design Arena and e-commerce store Koovs listed in 2014, then travel portal Yatra and e-commerce firm Infibeam followed two years later.

India has consistently attracted billions of dollars in funding in recent years and produced many unicorns. Those include Flipkart, which was acquired by Walmart last year for $16 billion, Paytm, which has raised more than $2 billion to date, Swiggy, which has bagged $1.5 billion to date, Zomato, which has raised $750 million, and relatively new entrant Byju’s — but few of them are nearing profitability and most likely do not see an IPO in their immediate future.

In that context, IndiaMART may set a benchmark for others to follow.

“The fact that we have a homegrown digital commerce business, serving both the urban and smaller cities, and having struggled and been around for so long building a very difficult business and finally going public in the local exchange is a phenomenal story,” Ganesh Rengaswamy, a partner at Quona Capital, told TechCrunch in an interview. “It keeps the story of India tech, to the Western world, going.”

Generally, it is agreed that there are too few IPOs in India and the industry can benefit from momentum and encouragement of high profile and successful public listings.

“There is a firm consensus that in India, markets will prefer only the IPOs of companies that are profitable. And investors in India might not value those companies. Both of these issues are being addressed by IndiaMART,” said Sawhney.

“We need 30 to 40 more IPOs. This will also mean that the stock market here has matured and understands the tech stocks and how it is different from other consumer stocks they usually handle. More tech companies going public would also pave the way for many to explore stock exchanges outside of India.

“Indian market is ready for more tech stocks. We just need to get more companies to go out there,” Sawhney added, although he did predict that it will take a few years before the vast majority of leading startups are ready for the public market.

The Indian government, for its part, this week announced a number of incentives to uplift the “entrepreneurial spirit” in the nation.

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman said the government would ease foreign direct investment rules for certain sectors — including e-commerce, food delivery, grocery — and improve the digital payments ecosystem. Sitharaman, who is the first woman to hold this position in India, said the government would also launch a TV program to help startups connect with venture capitalists.

The path ahead for IndiaMART

IndiaMART has managed to build a sticky business that compels more than 55% of its customers to come back to the platform and make another transaction within 90 days, Agarwal — its CEO — said. With some 3,500 of its 4,000 employees classified as sales executives, the company is aggressive in its pursuit of new customers. Moving forward, that will remain one of its biggest focuses, according to Agarwal.

“Most of our time still goes into educating MSMEs on how to use the internet. That was a challenge 20 years ago and it remains a challenge today,” he told TechCrunch.

In recent years, IndiaMART has begun to expand its suite of offerings to its business customers in a bid to increase the value they get from its platform and thus increase their reliance on its service.

IndiaMART has built a customer relationship management (CRM) tool so that customers need not rely on spreadsheets or other third-party services.

“We will continue to explore more SaaS offerings and look into solving problems in accounting, invoice management and other areas,” said Agarwal.

The firm also recently started to offer payment facilitation between buyers and sellers through a PayPal -like escrow system.

“This will bridge the trust gap between the entities and improve an MSME’s ability to accept all kinds of payment options including the new age offerings.”

There’s an elephant in the room, however.

A bigger challenge that looms for IndiaMART is the growing interest of Amazon and Walmart in the business-to-business space. Several startups including Udaan — which has raised north of $280 million from DST Global and Lightspeed Venture Partners — have risen up in recent years and are increasingly expanding their operations. Agarwal did not seem much worried, however, telling TechCrunch that he believes that his prime competition is more focused on B2C and serving niche audiences. Besides he has $100 million in the bank himself.

Indeed, as Quona Capital’s Rengaswamy astutely noted, competition is not new for IndiaMART — the company has survived and thrived more than two decades of it.

“Alibaba came and gave up,” he noted.

An important — and unanswered question — that follows the successful IPO is how IndiaMART’s stock will fare over the coming months. A glance to the U.S. — where hyped companies like Uber, Lyft and others have seen prices taper off — shows clearly that early demand and sustained stock performance are not one and the same.

Nobody knows at this point, and the added complexity at play is that the concept of a tech IPO is so uncommon in India that there is no definitive answer to it… yet. But IndiaMART’s biggest achievement may be that it sets the pathway that many others will follow.

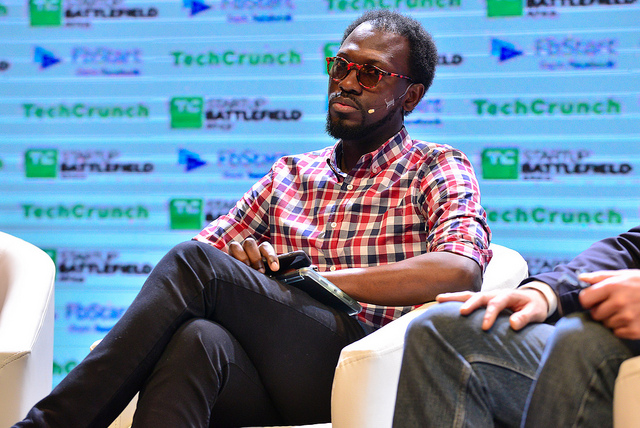

“There’s a lot of trade between Africa and China and this integration makes it easier for African merchants to accept Chinese customer payments.”

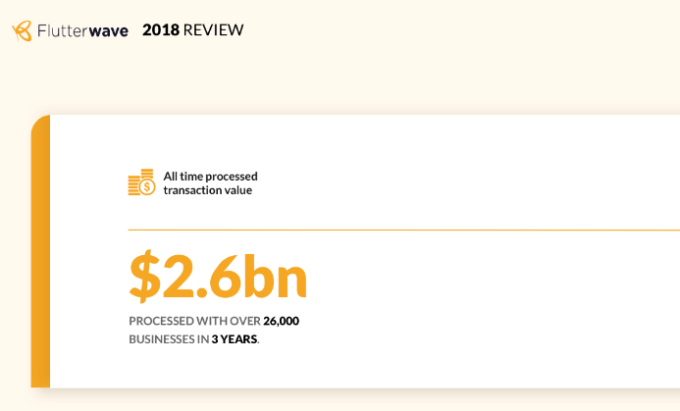

“There’s a lot of trade between Africa and China and this integration makes it easier for African merchants to accept Chinese customer payments.” Founded in 2016, Flutterwave allows clients to tap its APIs and work with Flutterwave developers to customize payments applications. Existing customers include

Founded in 2016, Flutterwave allows clients to tap its APIs and work with Flutterwave developers to customize payments applications. Existing customers include