As the enterprise device supply chain grows increasingly global and fragmented, it’s becoming more challenging for organizations to secure their hardware and software from suppliers. According to the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, the EU agency that contributes to the bloc’s cyber policy, 66% of cyberattacks focused on a supplier’s code as of 2021.

Combating these attacks is no easy feat — but Yuriy Bulygin is making a go of it. He’s the founder of Eclypsium, a cloud platform that provides protection against device hardware, firmware and software exploits in corporate environments and public sector environments.

In a reflection of investor confidence — or perhaps simply the demand for supply chain security solutions — Eclypsium today closed a $25 million Series B round led by Ten Eleven Ventures with participation from Global Brain’s KDDI Open Innovation Fund and J Ventures, bringing the company’s war chest to $50 million. Bulygin says that the capital will be put toward expanding Eclypsium’s product capabilities, supporting current sales efforts and expanding headcount from around 80 people to over 100 by the end of the year.

“A few macro-level trends are driving demand for Eclypsium’s solution, and therefore made this the right time to raise funding to enable accelerated growth,” Bulygin told TechCrunch in an email interview. “The global supply chain is increasingly complex, which means that finished devices may have hardware and firmware components sourced from vendors around the world — all of whom add to the risk and complexity of securing a device. Moreover, the White House’s continued focus on … creating resiliency in America’s supply chains has brought a new focus to the risks inherent in a global economy, and has also driven increased demand from government agencies in Eclypsium’s solutions.”

Prior to launching Eclypsium, Bulygin spent nearly a decade at Intel, where he led security threat analysis and directed research on software and hardware vulnerabilities and exploits. Bulygin went on to become the senior director of advanced threat research at McAfee before founding CHIPSEC, an open source platform security assessment framework.

In founding Eclypsium, Bulygin sought to build a service that — in his own words — helps companies avoid “falling into the trap” of relying on equipment manufacturers and more traditional endpoint security management tools. While some startups, like Finite State, provide firmware-based supply chain security for connected devices, Bulygin argues that this level of protection is an afterthought where it concerns most cybersecurity vendors.

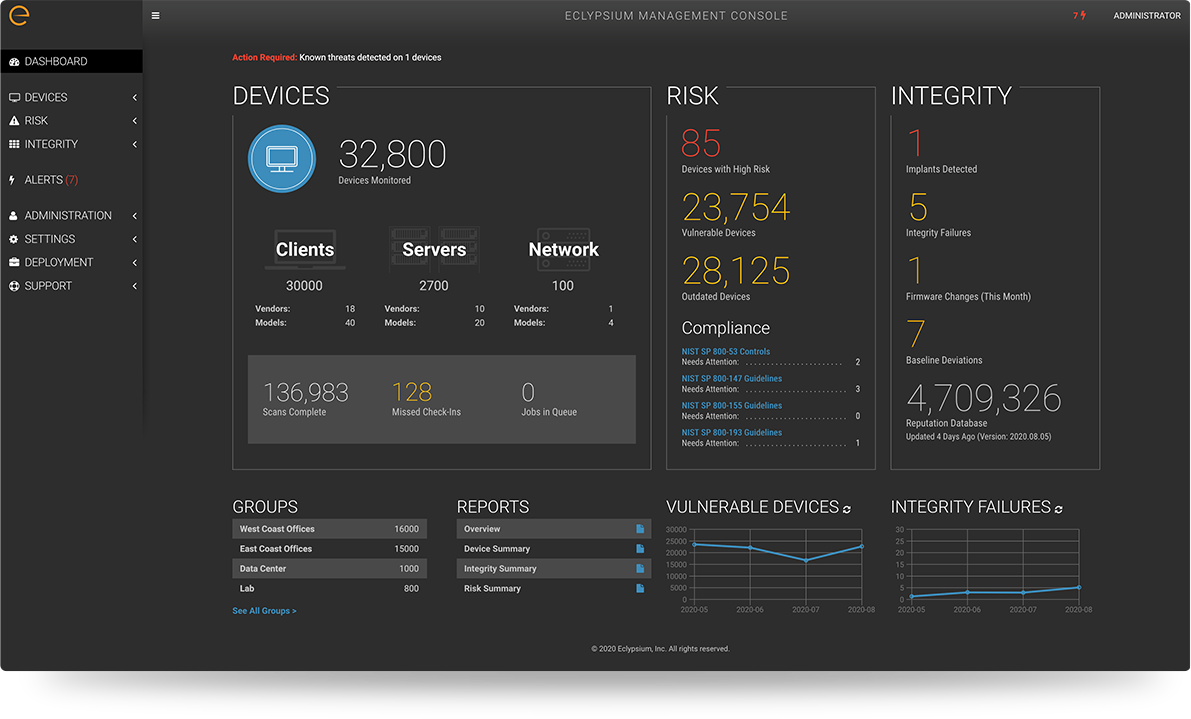

Eclypsium’s cloud management dashboard Image Credits: Eclypsium

The assertion has to be taken with a grain of salt — Bulygin has a product to sell, obviously. But all else being equal, it’s true that supply chain attacks are on the rise globally. According to a 2022 survey by Venafi, a machine identity management firm, 82% of chief information officers believe that their organizations are vulnerable to cyberattacks targeting supply chains. The report suggests the shift to cloud-native development, along with the increased speed brought by DevOps processes, made the challenges associated with securing supply chains significantly more complex.

“The sheer number and complexity of modern devices requires highly specialized understanding and expertise in equipment built by various manufacturers — with all firmware and software shipped with these devices — and requires a unique set of capabilities to detect compromised devices and protect from further compromise,” Bulygin said. “Because firmware plays such a critical role in enabling and defending our technology supply chains, many traditional security vendors have opportunistically added ‘firmware-specific features’ to their products. However, firmware security is not an add-on.”

Eclypsium supports hardware, including PCs and Macs, servers, “enterprise-grade” networking equipment and Internet of Things devices. Using the platform, organizations can see and control fleets of devices as well as networking infrastructure without having to install client software. Firmware orchestration capabilities allow security teams to go one step further, tapping Eclypsium to discover, analyze and deploy firmware updates published by device manufacturers to spot “unexpected” — and potentially malicious — software modules embedded in the hardware.

“Organizations are increasingly turning to zero trust principles to defend their device fleets and operations. As such, the default position is to avoid trusting systems and users until explicitly verified … [yet] each device represents a complex system of computers with their own embedded code and operating systems — each built by many suppliers,” Bulygin said. “Organizations need to understand all layers of hardware and software code for device verification to be truly successful, from all of the code embedded into devices and supplied by manufacturers to operating systems and applications. Software and firmware code embedded into devices is the most fundamental and privileged software running on each device.”

Bulygin was coy when asked about the size of Eclypsium’s customer base, and he declined to reveal any specific revenue figures. But Bulygin did volunteer that a third of the company’s customers are Fortune 2000 firms and that Eclypsium has a number of U.S. federal government contracts.

The pandemic shifted many organizations to a remote-first, work-from-anywhere, bring-your-own-device environment, accelerating the need to adopt defensive models and principles which don’t rely on perimeter defenses. The most notable shift is the move to zero trust principles, both at the application and the device level. This growing recognition of the need to provide multi-layered defense for devices, including at the operating system, embedded software and firmware, and hardware layers, has increased interest in supply chain … solutions for devices, like those from Eclypsium.

As funding rounds like Eclypsium’s shows, the cybersecurity bubble might be starting to deflate — but it hasn’t burst. Data from Momentum Cyber, a financial advisory firm, showed that cybersecurity startups raised a record-shattering $29.5 billion in venture capital in 2021, more than doubling the $12 billion raised in 2020, while a record number were minted as unicorns. And according to Crunchbase, venture dollars invested into cyber startups hit almost $6 billion in Q1 2022.

Eclypsium lands $25M to secure the device supply chain by Kyle Wiggers originally published on TechCrunch