All products are garbage, and for good reason

The bear and bull cases for Arm’s IPO

Arm, the British chip design firm owned by SoftBank, filed to go public yesterday evening, following years of speculation around an IPO after the company’s plan to merge with GPU giant Nvidia fell apart a few years ago.

This morning, we’re perusing the company’s F-1 filing to better understand its business, with a focus on its profitability and growth. Unlike many other IPO candidates we’ve covered in recent years, Arm is quite profitable, but it hasn’t been growing much lately.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

This is an important IPO for SoftBank, which poured billions of dollars into Arm when it bought the company. It’s also an important IPO for the market in general, particularly for startups, even if Arm is not the usual venture-backed business that we usually cover.

This is an important IPO for SoftBank, which poured billions of dollars into Arm when it bought the company. It’s also an important IPO for the market in general, particularly for startups, even if Arm is not the usual venture-backed business that we usually cover.

Why? Venture capitalists and founders alike are currently enduring a liquidity drought, which this IPO could help resolve. If the listing is received well, it could bolster confidence in the public markets, which could in turn spur more companies to list. For the hundreds of unicorns currently stuck in the private markets, that could be big news.

On the other hand, if Arm stumbles on its way out the gate or is forced to sell its shares for far less than it expects to, the IPO could limit startups’ confidence in venturing out into the public markets and limit the number of subsequent listings. Quite a lot seems to be riding on this IPO.

Will investors be impressed with what Arm has on offer? Let’s find out.

An Arm-ful of potential

To put it simply, Arm designs computer chips and makes money from companies that use its designs to build semiconductors. In practice, this means that the company generates very high-margin revenue, spends a large fraction of that revenue on research and development, and has serious competition.

Gear Patrol’s acquisition of DPReview shows that it can pay to be boring

In March, DPReview announced that parent company Amazon was shutting it down, and the photography world entered a dual state of shock and disbelief.

For 25 years, DPReview had served as a consistently reliable and authoritative voice on photography gear. But photography enthusiasts didn’t just go to DPReview to drool over Canon’s newest lens or compare Sony and Nikon’s face-detection autofocusing capabilities. It was an active forum where we (yes, I’m one of those photography people) could hang out and geek out.

That such an extensive archive of photography knowledge and the strong community it had fostered was being banished to the abyss — the plan wasn’t even to archive it but to switch it off completely — was a blow to many. The announcement on DPReview garnered over 5,000 comments, and people took to social media to share their thoughts about Amazon’s decision.

But that soon changed when Gear Patrol — which offers advice, how-tos and product reviews, but not specific to cameras — came to the rescue. It finalized a deal to purchase DPReview from Amazon for an undisclosed sum in June 2023. I was excited to speak to Eric Yang, Gear Patrol’s founder and CEO, to find out what motivated the purchase and what he learned from the process.

Authority and community

Yang was driven to bring DPReview under the Gear Patrol aegis for several reasons, and while it made business sense, there was a personal motivation there, too.

“It’s a business, so it’s not a totally altruistic endeavor,” Yang told me. “But DPReview is very meaningful to me. It’s meaningful to a lot of people, I think, who have grown up on the internet.”

DPReview is home to an extraordinary knowledge base that Yang was reluctant to see disappear. But this knowledge base doesn’t reside just in its vast archive of reviews, buying guides, editorials and advice; it’s also in the strong community that this expertise fostered. For so many people, DPReview was a safe place to express opinions, ask for advice, or just be photography geeks. All of this, together, was valuable to Yang.

A natural fit

Yang describes Gear Patrol as a place that empowers people to pursue their interests and passions with confidence, which is why he believes that Gear Patrol and DPReview are a natural fit. “We want to help people have the knowledge that they need to pursue their particular passions in the best possible way,” Yang said.

VR is dead

It’s hard to believe that it was only 11 years ago that VR captured the zeitgeist. In April 2012, Oculus hit Kickstarter with the Oculus Rift developer kit, and the tech world whipped itself into a “this is the future” frenzy. Facebook slapped a $2 billion check on the table and acquired the company in 2014.

But today, as it stands, VR is all but dead.

VR — as in, a system for being exclusively in virtual reality — barely exists as a concept anymore. Even the cheapest mainstream headset out there, the Meta Quest 2, has a passthrough feature, meaning it’s got AR capabilities. The Quest 3 adds higher-definition passthrough in full color. And, $3,500 price tag aside, Apple’s Vision Pro takes the concept so far that it doesn’t even really use the VR nomenclature anymore.

That’s because VR is missing the one crucial thing that could’ve taken it from “cool toy” to “must-have device”: a killer app. Even as the market has matured, VR is still struggling to find a reason to exist.

In 2015, TechCrunch published an article that speculated that the market could hit $150 billion of revenue by 2020. Here we are, nearing 2024, and it looks like the market sits at around $32 billion — a fifth of what the breathless analysts were guessing.

Apple’s AR headset is a game-changer for startups

TechCrunch tried out the Apple Vision Pro headset, concluding that it is very good — but perhaps also too good to be true. Apple has a long history of launching first-generation products that are pretty decent, before quickly following up with updates and amendments that make the original kit better.

From hardware engineers, you occasionally hear an under-breath muttered comment along the lines of “the third generation of X was the one we wanted to ship in the first place.” That isn’t uncommon in hardware; it’s pretty rare that a full product vision survives the constraints of supply chains and manufacturing. There’s a chasm of difference between building a single prototype of something, and building a few million of something.

Yes, the Apple Vision Pro is weighed down by its $3,500 price tag, and judging from the videos and cut-away photos alone, I’d be surprised if the company will make any money at all on the devices.

How did Apple wind up there? It appears that its engineers were given carte blanche to make the best device they could, solving some crucial problems along the way. To make this a standalone device (it can be used without being tethered to a phone or computer, although it does, awkwardly, have an external battery pack), the company packed an M2 processor into the headset, along with a brand-new R1 processor, which takes care of all the inbound data from the 12 (!) cameras, lidar, eye sensors, six microphones and more. The company says the device has 23 sensors in total.

Still, the preposterously over-engineered headset is a vital flag in the ground for startups.

It’s been more than a decade since the original Oculus Rift hit Kickstarter, with its 640×800 pixels per eye resolution, a product that was persistently plagued by complaints that it made people feel motion sickness. Since then, we’ve seen dozens of additional headsets launched. The $300 Meta Quest 2 is proving to be an important entry-level headset for the masses, while the $1,000 Meta Quest Pro and the $1,500 HTC VIVE Pro 2 are shoring up the high-end headset market. Apple’s device is launching at more than twice the price.

Apple’s AR headset is a game-changer for startups by Haje Jan Kamps originally published on TechCrunch

Apple’s new headset fails to excite investors, but sends shares of Unity soaring

In case you were not allowed to stop working long enough to tune into Apple’s series of product announcements Monday, let me catch you up: The Cupertino-based technology company has a new device coming out called the Vision Pro. It’s an augmented reality headset that, while it looks pretty spiffy and is packed with neat tech, is both expensive and not coming to its first market until early next year.

Given the sheer amount of anticipation that the Apple headset brought along with it, you might be slightly underwhelmed to learn that the Vision Pro will cost $3,499, and if you are not in the United States, it will take a rather long time to make it to your door.

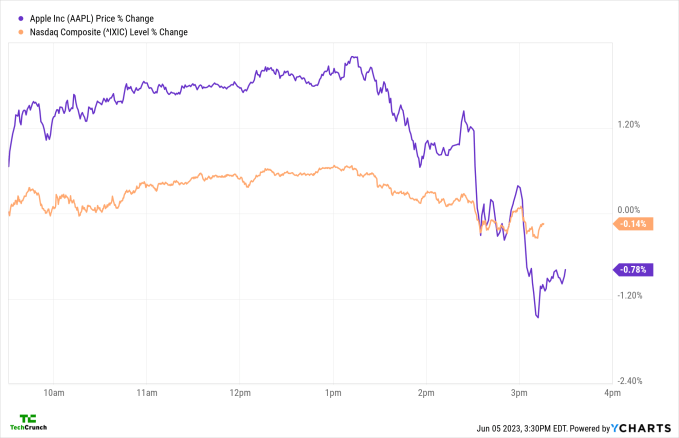

Investors in Apple shares bid the company’s stock to all-time highs ahead of the event. During the product informercial, shares of the company held up for a period, before losing steam along with the rest of the Nasdaq Composite index.

Observe the following chart, set to track percentage changes during the day:

Apple’s new headset fails to excite investors, but sends shares of Unity soaring by Alex Wilhelm originally published on TechCrunch

How to prepare a hardware startup for raising a Series A

The world we used to live in — the one that revolved around using cheap money to pump up ARR — is gone.

It came to a screeching halt with rising interest rates, and it’s not on its way back anytime soon. VCs responded as VCs do: by quickly shifting from a “growth-at-all-costs” mindset to focusing on instant profitability while funding metrics shifted from just revenue and growth to including costs as well.

Since the beginning of Q2, a spur of companies, including hardware companies, have come out of the gate and started raising money. The Silicon Valley Bank (and, more recently, Free Republic Bank) debacle has been relatively short-lived, but, given the multiple rollercoasters the industry has been on, one has got to wonder where the goalposts are nowadays.

There’s no debate that the SaaS game has changed, and yet a consensus on Series A funding metrics for these companies hasn’t emerged. However, it is not too difficult to guess that it would be roughly around double the revenue bar at the same or lower cost. It’s a challenging proposition, but a clear and tangible goal to strive for — and one that cannot be applied to hardware companies without revenue in their early stages.

So how can a hardware company raise a Series A amidst yet another “new normal” in this post-low-interest-rate era?

Commit to having deployable hardware

Most hardware companies barely get their product to function — and can only do so using their own engineers and technicians. Hardware in this situation is not deployable on any meaningful scale.

At the Series A stage, VCs want to know that they can pump money into a product that will start going into the market. This does not mean that the product needs to be pitch-perfect; it just means it has to be sufficiently mature to function in a more unconstrained environment outside of the startup lab.

At the Series A stage, VCs want to know that they can pump money into a product that will start going into the market.

Use your ratio of engineering support per hardware as a metric for whether your product is deployable in the way it needs to be. If you have one engineer for the hardware piece you are deploying (not to be confused with non-engineer technical support personnel for customers), you do not have a deployable product.

Now, at a one-to-four ratio, the unit economics become more reasonable. As a stretch goal, you should target to get the human out of the loop entirely, but everything eventually boils down to unit economics.

If you’re hitting 70+% gross margin at a reasonable price, then you can afford to have more support — but it is going to be exceptionally difficult to maintain as an early-stage company with an immature product.

Show tangible proof of high-quality demand

How to prepare a hardware startup for raising a Series A by Walter Thompson originally published on TechCrunch

Welcome to the trillion-dollar club, Nvidia

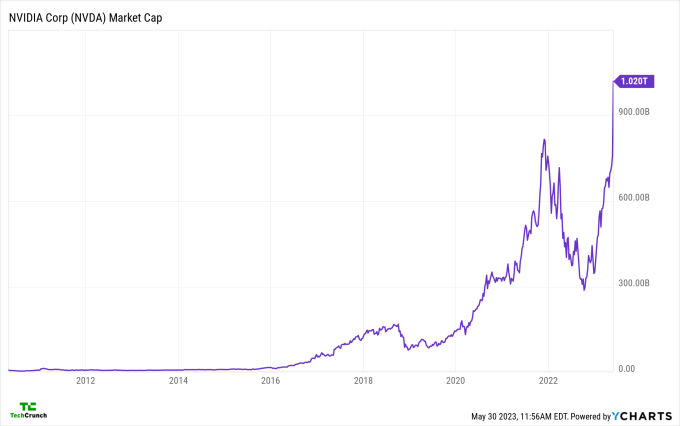

Welcome to the $1 trillion club, Nvidia.

Nvidia’s stock is up more than 6% today, pushing its shares past $413 in the wake of a widely-praised earnings report.

Given that the stock market has battered tech stocks in recent quarters, how is Nvidia breaking away from the pack? What can we learn from its rise?

The club of trillion-dollar companies, measured by market capitalization, is so small that even Meta doesn’t make the cut today. Tesla is only 63% of the way there and Salesforce is not even worth a quarter of the required value it needs to join. To see Nvidia reach a market value of more than $1,000,000,000,000 is therefore a massive endorsement not only of its trailing operating results, but also its anticipated future. Investors expect a lot from Nvidia.

The following chart shows its ascent:

Image Credits: Ycharts

To get our minds around what’s going on, let’s go through the company’s latest earnings report, consider what it is forecasting, and discuss how investors and analysts missed the mark with their own expectations.

A look back and ahead

Nvidia is not an enterprise software company, so when we look at its results, we do not see what SaaS companies tend to produce: consistent revenue growth coupled with incremental profitability gains.

Instead, in the first quarter of fiscal 2024 ended April 30, Nvidia posted the following:

Welcome to the trillion-dollar club, Nvidia by Alex Wilhelm originally published on TechCrunch

Venture leasing: The unsung hero for hardware startups struggling to raise capital

Global funding in February 2023 fell 63% from the previous year, with only $18 billion in investments. For robotics startups, it didn’t get any better: 2022 was the second worst year for funding in the past five years, and 2023 numbers are heading in the same direction.

This behavior from investors in the face of uncertainty and austerity is justified, especially when hardware companies burn cash faster than SaaS does. So, founders of robotics startups and other equipment-heavy businesses are left wondering whether they’ll be able to close their next funding round or if they’ll have to resort to acquisition.

But there’s a happy medium between costly debt loans and VC funding that works particularly well for hardware startups: venture leasing.

There’s a happy medium between costly debt loans and VC funding that works particularly well for hardware startups: venture leasing.

Hardware startups are better suited than software companies for this kind of financing because they have tangible assets, balancing the high-risk nature of the industry with a liability.

As the CEO of a robotics startup that recently got a $10 million venture leasing deal, I’ll outline the advantages of this type of agreement for hardware companies and how to land a win-win deal when closing a round isn’t an option.

Why are venture leasing deals compatible with hardware startups?

As opposed to a few developers here and there in SaaS, hardware companies require intensive Research and Development (R&D), capital expenditures (CapEx), and manual labor to manufacture their products. So, it’s no surprise that the latter’s cash burn rate is more than two and a half times higher than the former.

Hardware startups are constantly trying to avoid dilution when raising funds due to their capital-heavy operations. Therefore, venture leasing can be a relief for founders as it gives them the money they need up-front without compromising their company’s equity.

Rather than taking a piece of a company’s shares or equity, venture leasing takes the business’ physical assets as a liability to secure the loan—making it easier for startups to obtain it. It’s also a lower-risk investment and allows the company to keep 100% of their ownership.

These deals work like a car lease, where the bank technically owns the car (the manufactured product) while the startup pays a monthly installment to keep it and, in most cases, operate it however they want. Lenders are often more flexible with their agreement terms than other funders.

Beyond avoiding dilution, leasing theoretically takes a company’s equipment from its capital assets, allowing for more efficient margins in terms of profitability.

The added plus: Boosting Equipment-as-a-Service

With venture leasing, a startup can lease assets such as equipment, real estate, or even intellectual property from a specialized leasing company. They receive the assets in return for a monthly lease payment over a fixed term, typically shorter than traditional financing.

Venture leasing: The unsung hero for hardware startups struggling to raise capital by Walter Thompson originally published on TechCrunch