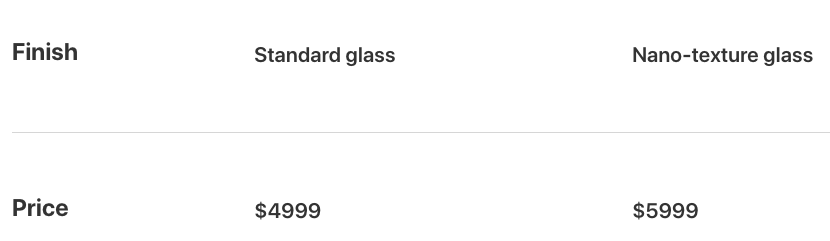

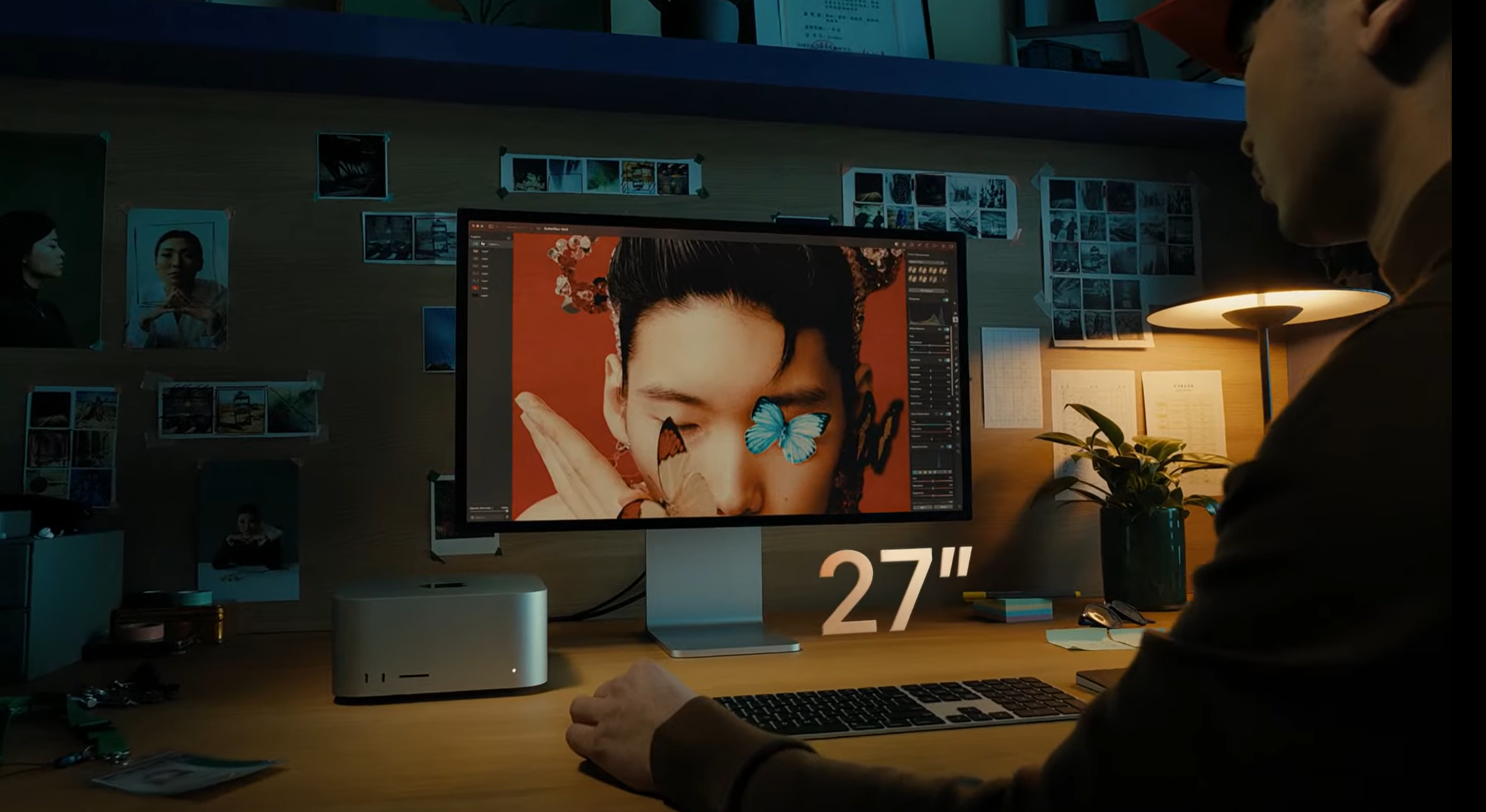

At Apple’s March event, the company announced the Studio Display, a new, 27 inch external monitor that starts at $1,599—a huge step down in price from the company’s only other monitor, the Pro Display XDR, which starts at $5,000.

The announcement of the Studio Display is big news for many who have been waiting for Apple to offer a replacement for its popular Thunderbolt Display, which was released more than a decade ago and was eventually discontinued in 2016 when Apple pulled out of the display business entirely. In the tech industry, I know many product designers that refused to give up their Thunderbolt Displays, keeping them limping along despite their limited resolutions and outdated ports, in the hope Apple might eventually release a successor.

When Apple discontinued the Thunderbolt Display, it left a large gap in the market: there are practically zero all-in-one displays that combine a monitor with a webcam, microphone, speakers, and USB ports into a single product. The LG Ultrafine was pushed by Apple as a solution, but it fell short in build quality, reliability, and connectivity compared with the Thunderbolt Display, despite sporting more the more modern USB-C port.

When the technology industry switched to working remote full-time in 2020 due to the pandemic, I was surprised by the lack of great options for all-in-one external displays when I was shopping for a new monitor. With USB-C popping up on almost every modern computer, promising high-speed connectivity, display support, and charging over a single cable, I had expected monitor companies might try to recreate the success of the Thunderbolt Display. But, I found few options when I looked for one and wound up ordering a simple 4K monitor, a separate Logitech webcam, USB hub and a microphone.

Apple’s new Studio Display is the answer, after a decade of waiting, and its specifications hit all of the right notes. It sports a 5K display (5120 × 2880 pixels) at a 60hz refresh rate with a wide P3 color gamut, a 12 megapixel webcam, three studio microphones for noise cancelling, six built-in speakers, and a Thunderbolt 3 port along with 3 USB-C ports for plugging in all of your peripherals. It plugs into a MacBook via a single Thunderbolt 3 USB-C cable, which also charges the laptop while it’s being used.

It stands out from the competition because it’s one of the few 5K resolution options available to buy, but also because Apple built in an A13 processor to add additional features such as True Tone, which adjusts the color temperature based on the ambient light in your room, as well as Center Stage which tracks you and keeps you in the frame of the webcam as you move around. While it might sound sort of dull, you can also control the brightness, sound levels, and other functionality directly from your Mac’s keyboard hotkeys instead of requiring navigating a cryptic on-screen display menu built into your screen, which is a massive quality of life improvement.

The most common complaint I’ve seen of Apple’s new display online is that it doesn’t support the company’s ProMotion technology found in its latest computers, which includes a high maximum refresh rate (120hz) that can only be described as buttery. This was never going to happen, however, because the port throughput required to pull this off doesn’t exist yet: 5K resolution at 120hz would require 53.08 gbps, but Thunderbolt 3/4 are only capable of carrying 40 Gbps over a single cable. This type of speed is reported to be coming as a part of the Thunderbolt 5 standard, but the new technology is yet to be announced publicly and isn’t available on any computers yet.

While many have balked at the $1,599 base price, I’d argue that all of this is actually well worth it for folks that need a high resolution, color accurate display and spend most of their day in front of a screen, especially if they work from home—which is especially true of anyone working in the product design industry, such as myself, but it’s compelling for anyone who’s in meetings all day and would like to ditch all of the accessories.

Being able to plug in a single cable and have a webcam, microphone, and speakers ready to roll for your next video call is a massive improvement over fiddling around every time you’ve unplugged your laptop, especially considering that the integrated microphones are optimized for noise cancelling to make taking video calls on the speakers tolerable for everyone involved. For companies hiring on remote employees, being able to ship out a single screen that includes all of the accessories they’re going to buy individually anyway, is likely to make it a popular choice for enterprise buys.

Is the Studio Display expensive? Absolutely, but it’s an investment in something you’re likely using all day, and will get years of use out of if the Thunderbolt Display’s legacy is anything to go by. I never thought I’d be dropping $1,599 on a screen but didn’t hesitate to order one the moment it was available, because life’s too short for bad screens and having webcams perched precariously on top of them.