“Product thought leaders talk about an ideal way of working. Nobody actually works that way.”

I can’t tell you how many times I hear this sentiment on Twitter and LinkedIn. And I hate it.

I realize that many product people have never worked in a product trio, don’t have access to customers, aren’t given time to test their ideas, and are working in what Marty Cagan calls “features teams” or “delivery teams.”

And just the same, many people do work in product trios, interview customers, test their ideas, and work on empowered product teams.

Both are true. The reason why it’s so hard for the first group to believe that the second group exists is because they’ve never seen it.

But just because you’ve never seen it or experienced it, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. Especially when your experience only spans a half a dozen or so different workplaces.

To help highlight that real teams do work this way, we ran our inaugural CDH Benchmark Survey this past fall, where we asked teams about their discovery habits.

This is the second post about this survey. If you missed the first one on product success and team satisfaction, be sure to start there. It covers who we talked to, how we found them, and explained the goals of the survey. This post will pick up where it left off.

Shifting From Outputs to Outcomes

Good discovery starts with a clear outcome. Your outcome sets the scope for your discovery. It keeps us focused and ensures that we create value for the business while meeting customer needs.

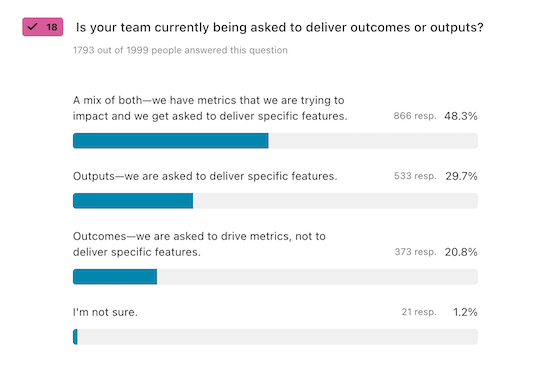

We asked teams about their habits related to setting outcomes, starting with, “Are you being asked to deliver outputs or outcomes?”

Good discovery starts with a clear outcome. Your outcome sets the scope for your discovery. In the #CDHBenchmarkSurvey, we asked teams, ‘Are you being asked to deliver outputs or outcomes?’ – Tweet This

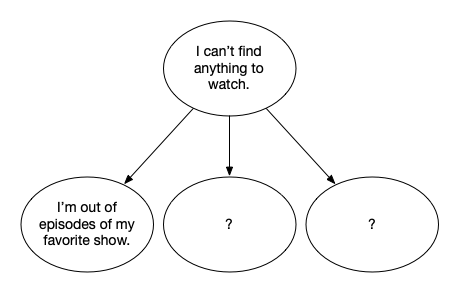

Before answering this question, respondents saw this description of outcomes vs. outputs:

Outcomes vs. Outputs

An outcome is a metric that measures the impact of your work. It’s typically derived from your business model (e.g. business outcomes) or represents a behavior your customer does in your product (e.g. product outcomes).

Outputs are the things that we produce—for product teams this usually means features, initiatives, or programs.

OKRs are a popular way of expressing an outcome.

The majority of respondents said their teams are asked to deliver a mix of outcomes and outputs.

I was not surprised to see the most common response (48.3%) was: “A mix of both—we have metrics that we are trying to impact and we get asked to deliver specific features.” Most of us are still learning to start with outcomes and change often happens slower than we want.

I was thrilled to see that 20.8% selected: “Outcomes—we are asked to drive metrics, not to deliver specific features.”

For the 30+% who selected “Outputs—we are asked to deliver specific features” or “I’m not sure,” don’t be discouraged. You can start to build your own outcome mindset before your organization catches up. Doing so will help you build better products regardless of your organizational context. If you want help building your outcome mindset, check out our Defining Outcomes course.

Even if your organization isn’t outcome-focused, you can start to build your own outcome mindset before your organization catches up. Doing so will help you build better products regardless of your organizational context. – Tweet This

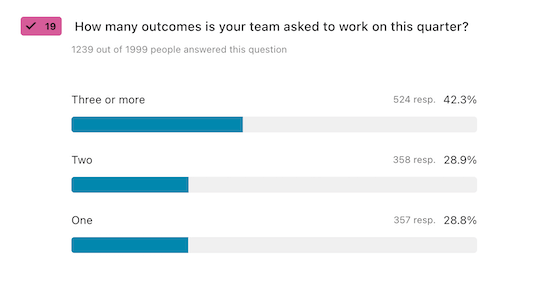

For the teams who selected “Outcomes” or “A mix of both,” we then asked, “How many outcomes is your team asked to work on this quarter?”

When asked how many outcomes their teams are working on, the majority of respondents said three or more. Ideally, this number should be much lower.

The results for this question are interesting. I know from working with many teams that most still have several outcomes. We are collectively trying to do too much at once.

I firmly believe that when teams work on one outcome at a time, they have a greater overall impact. When teams are split across multiple outcomes, they get pulled in too many directions and make incremental progress on each at best. I’d rather see outsized progress on one.

Only 28.8% of #CDHBenchmarkSurvey respondents said they were working on one outcome. I firmly believe that when teams work on one outcome at a time, they have a greater overall impact. – Tweet This

It’s clear from these results that focusing on a single outcome is still a minority position. However, I hope to make the case for this in my next blog post about this survey when I connect the different habits to product success.

In hindsight, for teams who are tasked with several outcomes, I should have asked if they had individual outcomes or if their team shared responsibility for several outcomes. I’ll be sure to add that to next year’s survey.

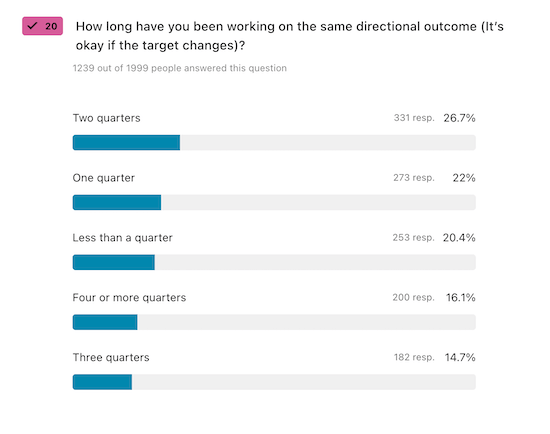

The survey explained that outcomes tend to have a directional component (e.g. increase engagement) and a target (e.g. by 10%). We wanted to understand how long a team had been working on the same directional outcome even if the target changed quarter over quarter.

Generally, I want to see a team focused on the same directional outcome over time. It takes time to learn how to impact a metric and the longer a team spends on an outcome, the more impact they’ll have. If you do a good job of deriving your outcomes from your business model, they shouldn’t need to change that often.

This doesn’t, however, mean that the way that you measure an outcome will stay constant. For example, a team might spend a year focused on increasing engagement. When they first get started, they might start by measuring daily active users. As they learn more, they might evolve to measuring DAU/MAU (daily active users divided by monthly active users). And with more time, they might define and refine specific high-value activities that count as usage. As we learn more about what makes our customers successful, we should develop better ways of measuring that success.

When I asked how long teams had been working on the same directional outcome, responses were spread pretty evenly across the options.

We asked, “How long have you been working on the same directional outcome?” and the responses were spread pretty evenly across the options.

- Less than a quarter (20.4%)

- One quarter (22%)

- Two quarters (26.7%)

- Three quarters (14.7%)

- Four or more quarters (16.1%)

In my experience, teams make more progress in their second quarter working on an outcome than they do in the first. That’s because they incur a big learning tax in the first quarter that they are working on an outcome. I was thrilled to see that 57.5% of respondents were working on the same directional outcome for at least 2 quarters. I hope this trend continues.

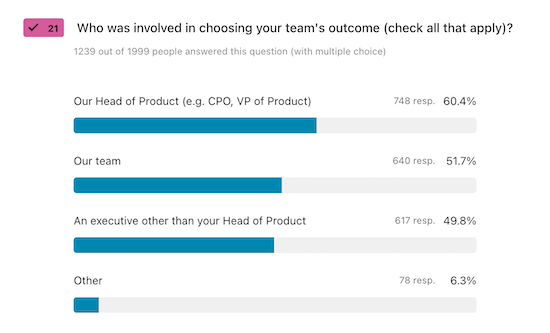

We also asked respondents who in their organization was involved in setting their outcomes. Respondents were able to select multiple answers.

I asked who was involved in choosing outcomes and was surprised to see that such a large percentage of teams said both their team and leadership were involved.

60.4% of respondents said that their Head of Product (e.g. CPO, VP of Product) was involved. 51.7% said their team was involved. 49.8% said an executive other than their head of product was involved, and 6.3% said other.

In an ideal world, outcomes should be set by both the product team and executive leadership. Participants were able to select multiple items and here’s how the combinations broke down:

- Just our product team (14.47%)

- Just executives (44.54%)

- The team plus any executive leadership (36.38%).

In my experience coaching teams, it seems like either the team picks their outcome (with little to no input from leadership) or leadership picks the outcome (with little to no input from the team). So I was surprised to see that 36.38% of respondents said that both their team and leadership were involved.

The “Other” responses were a reminder that people don’t have great reading comprehension on the web. The most common responses were “CEO” and “Head of Product” (which were both options they could have selected). Other common responses included the product manager, the sales team, the CTO (again, one of the options), and Directors of Product or Engineering.

Understanding Team Exposure to Customers

I’ve long said that the keystone habit to discovery is regular engagement with customers. When we connect with customers on a regular basis, we get exposed to the gap between how we think about our products and how our customers think about them. When teams see this gap, they tend to be motivated to overcome it. They tend to interview more and run more assumption tests.

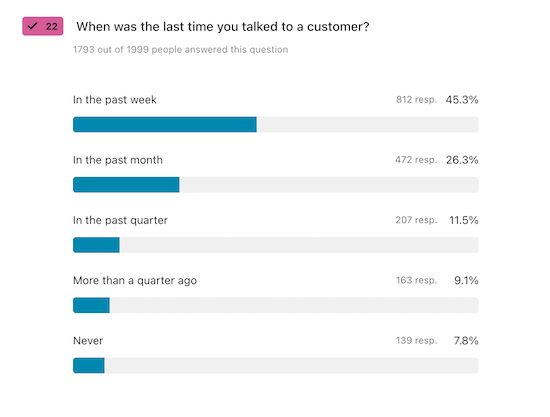

So naturally, we asked, “When was the last time you talked to a customer?”

I asked participants when they last spoke to a customer and I was happy to see 45.3% said in the past week.

I was happy to see that 45.3% of respondents said “In the past week.” 26.3% said “In the past month,” 11.5% said “In the past quarter,” 9.1% said “More than a quarter ago,” and 7.8% said “Never.”

45.3% of #CDHBenchmarkSurvey respondents said they have talked to a customer in the past week. 26.3% said they talked to a customer in the past month. – Tweet This

But before we get too excited about these results, I know that for many of these respondents, “talking to a customer” often means getting pulled into a sales call or being consulted on a support ticket. While these are important activities, they aren’t a replacement for good customer interviews.

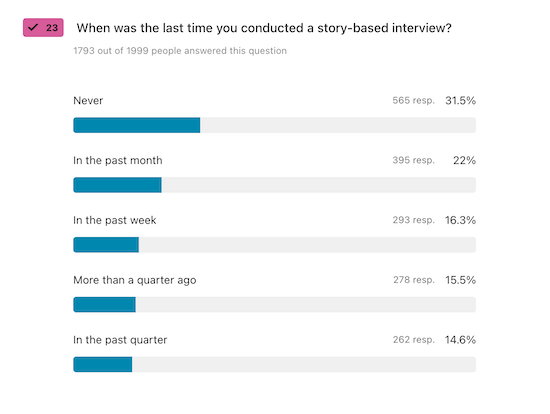

So we also asked, “When was the last time you conducted a story-based interview?” Now I know that story-based interviewing isn’t the only way to interview customers. But I do believe it is the most reliable way to learn about our customers (aside from observing them).

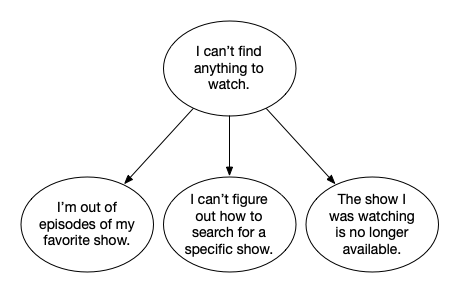

We didn’t assume that people knew what story-based interviewing was, so we showed them the following description before asking:

A story-based interview is where the interviewer keeps the participant grounded in a specific story about their past behavior.

For example: “Tell me about the last time you watched Netflix.”

Not: “Tell me about your experience on Netflix.”

Not: “What do you like to watch on Netflix?”

Not: “Would you watch this on Netflix?”

I’m thrilled to see so many respondents say they conducted a story-based interview last week. Yes!

I was pretty happy with the results:

- In the past week (16.3%)

- In the past month (22%)

- In the past quarter (14.6%)

- More than a quarter ago (15.5%)

- Never (31.5%)

It wasn’t too long ago that I was regularly criticized for being too idealistic when I suggested teams talk to customers every week. I’m thrilled to see that 293 of our respondents said they conducted a story-based interview last week. Yes! I also know that it takes time to get to this cadence, so I was equally thrilled to see that an additional 395 had conducted a story-based interview in the last month.

While these results do indicate we have more work to do—with 47% respondents having either never conducted a story-based interview or having done so more than a quarter ago—they also represent tremendous progress.

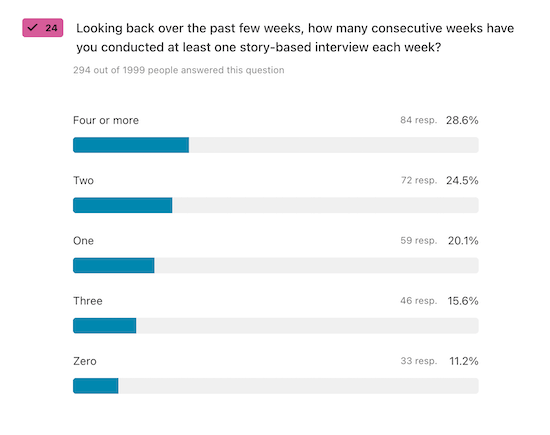

This question asks about one moment in time—last week. I also wanted to know who was building a habit of weekly interviewing. So for people who said they interviewed last week, we also asked, “Looking back over the past few weeks, how many consecutive weeks have you conducted at least one story-based interview each week?”

It was exciting to see that 28.6% of respondents had been interviewing weekly for at least four weeks in a row.

And here were their responses:

- Zero (11.2%)

- One (20.1%)

- Two (24.5%)

- Three (15.6%)

- Four or more (28.6%)

I was thrilled to see that 28.6% of respondents who said they interviewed last week had a 4 or more week streak going. That’s a sign of a strong habit.

28.6% of #CDHBenchmarkSurvey respondents who said they interviewed last week indicated that they had a 4+ week interviewing streak. Yes! That’s a sign of a strong habit. – Tweet This

I was not surprised to see that most folks are still struggling to build a habit. This is still a new idea for most teams and it takes time to turn this into a sustainable habit.

I was confused by the high percentage of people (11.2%) who said zero. They only saw this question if they said they had interviewed in the previous week, so at a minimum they should have chosen 1.

Synthesizing What You Learn from Interviews

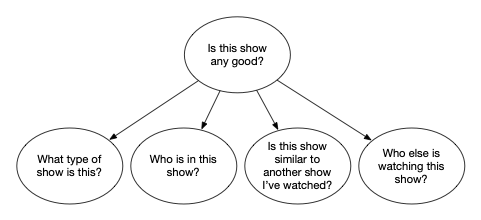

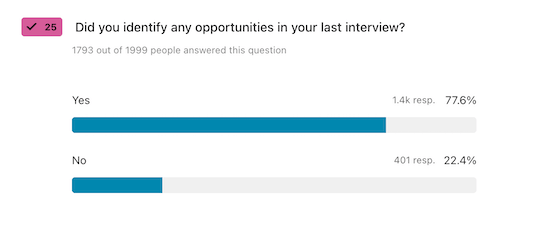

While there is some benefit from mere exposure to customers, the real value comes from synthesizing what we are learning in our interviews. To understand teams’ habits in this area, we asked a series of questions. We started with, “Did you identify any opportunities in your last interview?”

We didn’t assume that respondents would know what we meant by “opportunity,” so we defined it as follows before they saw the question:

I was surprised to see that 77.6% of respondents said they’d identified opportunities in their last interview because I find most teams aren’t clear on the definition of “opportunity.”

I was surprised to see that 77.6% of respondents said yes. In my experience coaching teams, this is not an automatic next step. And I find that most teams aren’t clear on what counts as an opportunity and what doesn’t. I realize now that I also should have asked those who said yes to share an opportunity from their last interview, so I could better assess if we mean the same thing by “opportunity.” I’ll add that to next year’s survey.

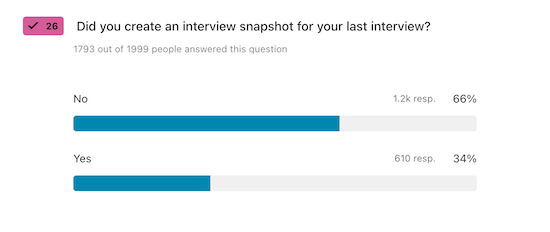

We also asked, “Did you create an interview snapshot for your last interview?” Interview snapshots are a way to visually synthesize what you are learning from each interview. They are by no means required (there are other techniques for synthesizing what you learned), but it’s the one that I recommend, so I wanted to measure how many teams were adopting them.

I was thrilled to see that 34% of respondents created an interview snapshot from their last interview—it’s always nice to see how something you created has an impact on teams.

Creating interview snapshots regularly takes discipline and I know many good continuous discovery teams who don’t bother. So I was thrilled to see that 34% of respondents said yes. This one was rewarding for me. It’s always nice to see how something you created has an impact on teams.

34% of #CDHBenchmarkSurvey respondents who conducted an interview said they created an interview snapshot afterwards. I love seeing teams adopt this practice. – Tweet This

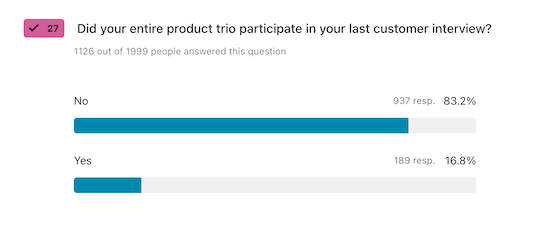

Product Talk readers know that I recommend product trios interview together. To assess how teams are doing, for the teams who earlier indicated that they worked in a product trio, we asked, “Did your entire product trio participate in your last customer interview?”

I was disappointed to see that the majority of respondents said their entire trio hadn’t participated in their last customer interview.

While the responses here didn’t surprise me, they did disappoint me. I really had hoped we had made more progress on this front. Only 16.8% of respondents said yes, whereas 83.2% said no.

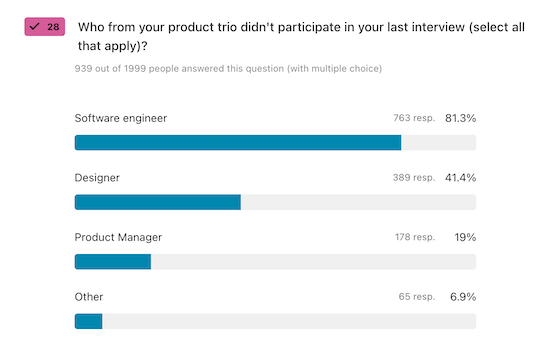

For the folks who said no, we asked, “Who from your product trio didn’t participate in your last interview? (select all that apply)”

For the majority of respondents, their engineer was missing from their last customer interview.

I was not surprised to see that 81.3% of the respondents said that engineering was missing. Far too many companies still think the only value engineers offer is writing code. I would love to see us make much more progress on this front.

81.3% of #CDHBenchmarkSurvey respondents (who did not interview as an entire product trio) said their engineers were missing from the interview. Let’s get more engineers involved in discovery! – Tweet This

41.4% of respondents said the designer was missing and 19% of respondents said the product manager was missing. I suspect these results were heavily influenced by the fact that an overwhelming majority of our respondents were from the product management function (69.43%).

These results indicate that we still have work to do when it comes to collaborating as a trio. I’m a strong proponent of trios because they ensure you bring different perspectives into your interviewing and decision-making.

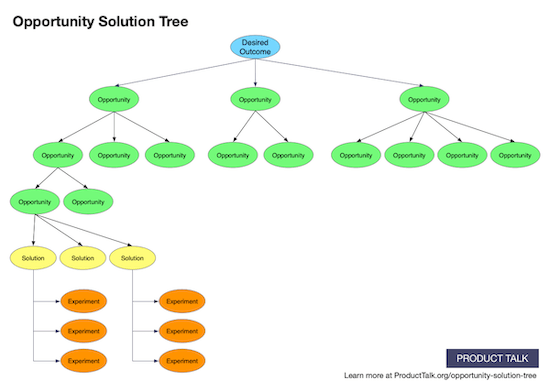

Visualizing Your Thinking: Experience Maps, Opportunity Solution Trees, and Story Maps

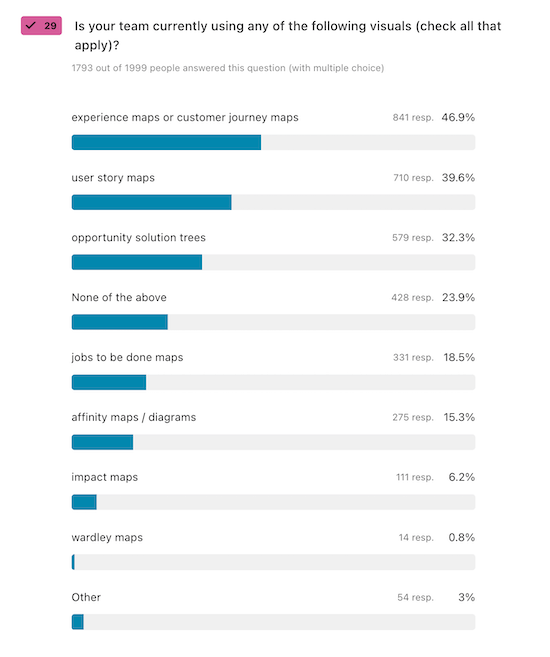

One of the key themes in my book Continuous Discovery Habits is for teams to visualize their thinking. The book includes a number of visuals designed to help teams align and examine their thinking including opportunity solution trees, experience maps, story maps, and much more.

We wanted to better understand who was adopting which visuals and how they were integrated into their day-to-day work.

We started by asking, “Is your team currently using any of the following visuals? (check all that apply)”

Respondents tend to use experience maps and customer journey maps—a result that’s not too surprising since these are both broad categories and well-known techniques.

Experience maps and customer journey maps were the most commonly used visuals (46.9% of respondents), followed by user story maps (39.6% of respondents), opportunity solution trees (32.3% of respondents), jobs to be done maps (18.5% of respondents), affinity maps/diagrams (15.3% of respondents), impact maps (6.2% of respondents), and Wardley maps (0.8% of respondents). 23.9% said they weren’t using any of these visuals and 3% said they were using some other visuals.

Customer journey maps and experience maps were the most commonly reported visual used (46.9% of #CDHBenchmarkSurvey respondents), followed by user story maps (39.6%), and opportunity solution trees (32.3%). – Tweet This

I’m not surprised that experience mapping and customer journey mapping came out on top. These are broad categories and are well-known techniques.

I was thrilled to see user story maps and opportunity solution trees not too far behind.

I was surprised to see that 23.9% of respondents aren’t using any visuals. I have a hard time imagining good product trio collaboration without them. I’ll be looking at the relationships between the different variables in a different post and will be excited to see how the use of visuals impacts team collaboration and team satisfaction.

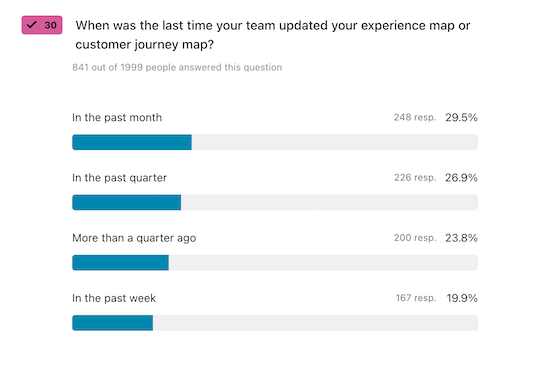

I’ve met a lot of teams who are good at creating an experience map or customer journey map one time, but then never revisit it or update it as they continue to learn. So for respondents who said they used experience maps or customer journey maps, we asked, “When was the last time your team updated your experience map or customer journey map?”

I’m happy to see that many teams are frequently updating their experience maps or customer journey maps.

I was happy to see that 19.9% of respondents said in the past week, 29.5% said in the past month, and 26.9% said in the last quarter. That tells me that these artifacts are living documents as intended. 23.8% of respondents said it’s been more than a quarter since they’ve updated their experience maps or customer journey maps.

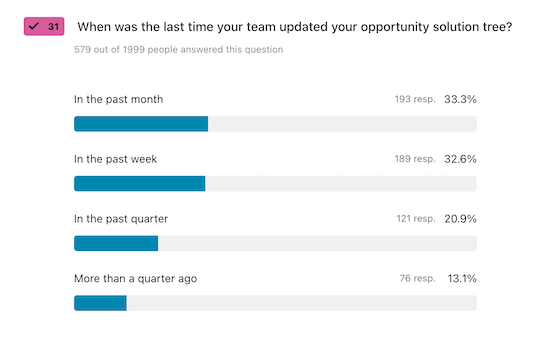

For respondents who said they used opportunity solution trees, we asked them, “When was the last time you updated your opportunity solution tree?”

The number of people who said they’d updated their opportunity solution tree in the past week or month tells me most teams are using opportunity solution trees as intended.

As a general rule, I want to see teams update their opportunity solution tree every 3–4 interviews. If they are interviewing weekly, that’s at least once a month. So I was thrilled to see that 32.6% of respondents said in the past week and 33.3% said in the past month. That tells me that most teams are using their opportunity solution trees as intended.

20.9% of respondents said in the past quarter and 13.1% of respondents said more than a quarter ago. I tend to see teams drop off from updating their opportunity solution tree when they have a hard time building a sustainable interviewing habit. We’ll see if this relationship holds up in the next post when we look at relationships between the variables.

Getting Value Out of Opportunity Solution Trees

One of the most common ways people misinterpret the intent of an opportunity solution tree is they think they can map the opportunity space without talking to customers. This kind of makes sense. Most product teams have some knowledge of their customers’ needs, pain points, and desires.

Teams are constantly inundated with feature requests, sales feedback, new trends from behavioral analytics, and so much more. But these sources rarely contain enough context for a team to really understand the need, pain point, or desire at any depth. It’s hard to truly solve for an opportunity if we don’t fully understand it.

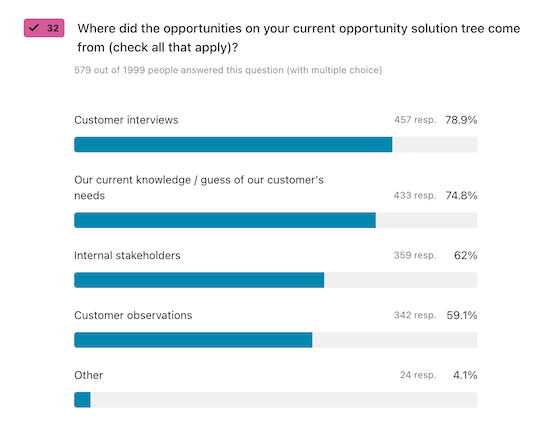

I like to see teams source opportunities from customer interviews and observations, not from previous knowledge (e.g. often assumptions) or internal stakeholders. So we asked teams, “Where did the opportunities on your current opportunity solution tree come from? (check all that apply)”

I’m concerned to see how many respondents said their opportunities came from their current knowledge or internal stakeholders instead of directly from customers.

I was very happy to see that 78.9% of respondents said customer interviews and 59.1% said customer observations. That second number really surprised me. I recommend interviewing over observations, because it’s easier to interview every week than it is to observe customers every week. But observations are a fantastic source of opportunities and I’m glad to see that so many teams are doing them.

74.8% of respondents said opportunities came from their current knowledge or a guess of their customers’ needs and 62% said opportunities came from internal stakeholders. These responses concern me. To be clear, I think internal stakeholders and team members can speculate about customer opportunities, but we need to verify that these opportunities are real by hearing about them directly from customers. This tells me that while many teams are adopting the opportunity solution tree as a way to visualize their thinking, they are missing some of the core benefits of the framework.

Only 3.8% of respondents limited the opportunities on their opportunity solution tree to the ones they are hearing in interviews or are observing directly. If you want to dive into why this is so important, start with this article on sourcing opportunities and then read this one about why these other sources of data are not enough.

Another common challenge for people who are new to opportunity solution trees is it’s hard to break their project mindset and develop a truly continuous mindset. Most of us are used to working on several-week or even multiple-month projects. And as a result, we tend to define large opportunities and work with too many at once.

Instead, I prefer that as people move vertically down the opportunity space, they learn to break big opportunities into smaller and more solvable opportunities. When you get good at this, you should be able to discover and deliver teeny-tiny solutions to teeny-tiny opportunities.

Each iteration contributes to a cohesive whole and chips away at the harder opportunities higher up on the tree. This is what unlocks a truly continuous mindset, as you are able to discover and deliver solutions for a single opportunity and then quickly move on to the next opportunity.

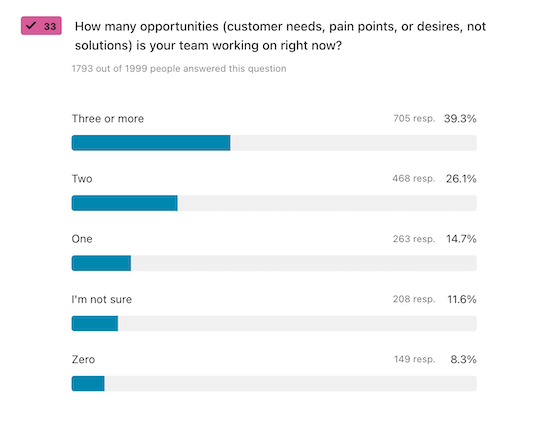

To assess how well teams are doing this, we asked, “How many opportunities (needs, pain points, and desires, not solutions) is your team working on right now?”

I suspect that many teams are taking on too many opportunities at once and not having their desired impact as a result.

Only 14.7% of respondents said 1. This is not terribly surprising. We all still assume we can do way more than we can. Also, as teams are learning how to accelerate their discovery cycles, it might make sense to work on 2 or 3 opportunities at a time. They might be brainstorming new solutions for one, while waiting for assumption tests results for a second, while delivering a third.

For the 26.1% who said 2 and the 39.3% who said 3 or more, if their opportunities are flowing through ideation, assumption testing, and delivery and there’s one opportunity in each stage, that’s fine. But I suspect many of these teams are biting off more than they should. It takes a giant leap of faith to trust that you can have more impact by limiting work in progress and focusing on one thing at a time. Even I struggle with this.

Another key benefit of an opportunity solution tree is it helps us see where we are comparing and contrasting options and where we are getting stuck in whether or not decisions.

Based on what we know from decision-making research, I want to see teams working with multiple solutions for the same target opportunity.

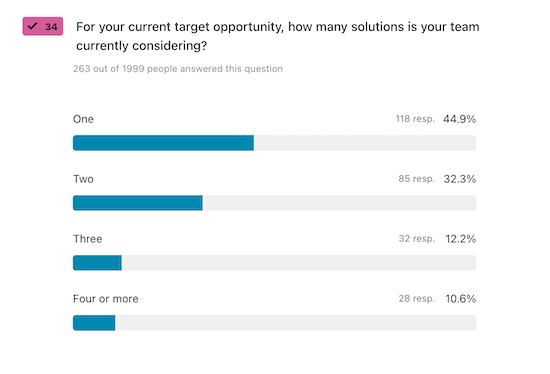

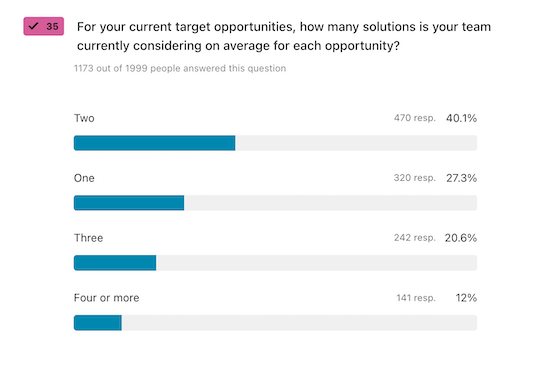

For teams who were working on one opportunity at a time, we asked, “For your current target opportunity, how many solutions is your team currently considering?” And for teams who are working on several opportunities at once, we asked, “For your current target opportunities, how many solutions is your team currently considering on average for each opportunity?”

For teams working on one opportunity at a time, the majority are considering one solution.

For teams working on more than one opportunity, a larger percentage are considering multiple solutions.

These results are interesting. For teams who are working on one opportunity at a time, 44.9% said they are considering 1 solution, 32.3% said 2 solutions, 12.2% said 3, and 10.6% said 4 or more.

Meanwhile, for teams who are working on multiple opportunities at once, 27.3% said they were considering on average 1 solution per opportunity, 40.1% said 2 on average, 20.6% said 3 on average, and 12% said four or more.

I’m skeptical of these results. I find it hard to believe that more teams who are working with multiple opportunities at the same time (40.1% of them) are exploring 2 solutions on average, when only 32.3% of teams who are working on one opportunity are exploring 2 solutions. I have a feeling the “on average” tripped people up here and we may not have collected reliable data. I’ll think about ways to improve that for next year’s survey.

Either way, too many teams are still working with one idea at a time. For teams who are working on multiple ideas, I’d love to learn if these are true compare and contrast situations or if these are multiple solutions in development.

Understanding Where Solution Ideas Come From

Ideas can and should come from anywhere. Research on ideation suggests that the more people involved in ideation, the more ideas we’ll generate. The same research suggests the more ideas we generate, the better ideas we have.

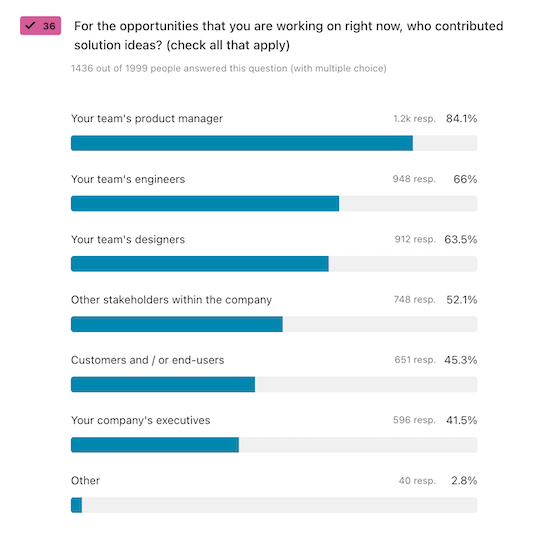

So we asked respondents, “For the opportunities that you are working on right now, who contributed solution ideas? (check all that apply)”

It looks like a lot of people are contributing solution ideas, but because respondents could select multiple options, the reality is more complicated.

84.1% of respondents said their product manager contributed ideas, 66% said engineers contributed ideas, 63.5% said designers contributed ideas, 52.1% said other stakeholders contributed, 45.3% said customers contributed, and 41.5% said the company’s executives contributed. This makes it look like a lot of people are contributing ideas. But because people were able to select multiple options, the reality is more complicated.

11.7% of respondents chose only one option. For this group, their responses broke down as follows:

- Just product managers (33.53%)

- Just designers (10.18%)

- Just engineers (19.16%)

- Just executives (16.17%)

- Just other stakeholders (12.57%)

- Just customers (8.38%)

18.43% of respondents indicated that product managers, executives, stakeholders, and customers contributed ideas. This group might represent a more traditional model where product managers work with stakeholders to “gather requirements.” It unfortunately leaves designers and engineers out of the process.

6.52% of respondents indicated their product team members were not involved in ideation—only executives, other stakeholders, and customers contributed ideas. It’s clear these teams are not empowered to generate their own ideas.

20.67% of respondents indicated that executives, stakeholders, and customers did not contribute ideas—only their product manager, designer, and/or engineers.

On a positive note, 46.11% of respondents indicated that their product manager, their designers, and their engineers contributed ideas. This is a great indication that we are making progress on truly collaborative product trios.

46.11% of #CDHBenchmarkSurvey respondents said their product manager, designers, and engineers contributed ideas. This is a great indication we are making progress on truly collaborative product trios. – Tweet This

And 10.23% of respondents indicated that all of these roles contributed ideas. As long as the product trio is empowered to test and decide which ideas to pursue, I think this is optimal. I like to see ideas coming from everywhere.

Evolving Solutions: Getting to Good Ideas

When a team is engaged in continuous discovery, their solution ideas should be constantly evolving. Bad ideas should be thrown out. Mediocre ideas should be improved. It’s rare that a good idea is simply found. Instead, we have to work to evolve our ideas into solutions that might work for our customers.

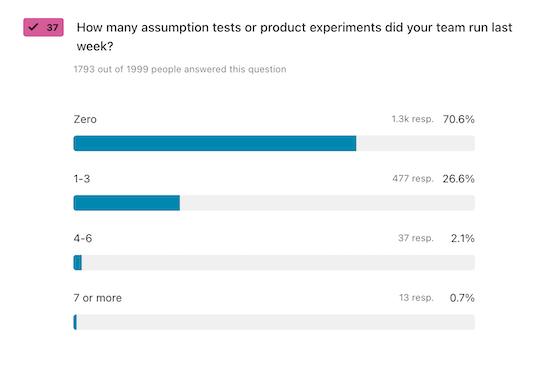

The best way to learn what’s working with an idea and what’s not is to run assumption tests. We asked respondents, “How many assumption tests or product experiments did you run last week?”

Assumption testing is one of the hardest habits to build, so I’m not surprised to see the majority of teams didn’t run any tests last week.

A whopping 70.6% of respondents said zero, 26.6% said 1–3, 2.1% said 4–6, and 0.7% said 7 or more. This is not surprising. We see this same trend with the teams that we work with and in our community.

Assumption testing is one of the hardest habits to build. We still have a long way to go here. If you want help building this habit, check out our Identifying Hidden Assumptions and Assumption Testing courses.

An overwhelming majority of #CDHBenchmarkSurvey respondents (70.6%) did not run a single assumption test in the prior week. This is one of the hardest discovery habits to build. – Tweet This

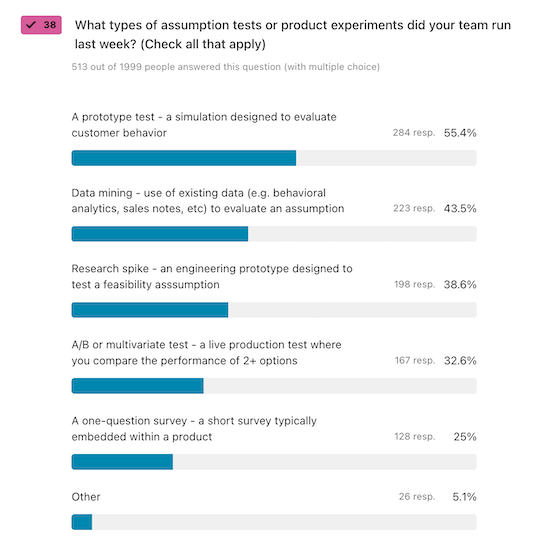

For the folks who answered 1 or more, we also asked, “What types of assumption tests or product experiments did you run last week? (check all that apply)”

The most common type of assumption test or experiment is a prototype test, followed by data mining.

I was not surprised to see prototype testing come out on top. Here’s the breakdown:

- A prototype test—a simulation designed to evaluate customer behavior (55.4%)

- Data mining—use of existing data (e.g. behavioral analytics, sales notes, etc.) to evaluate an assumption (43.5%)

- Research spike—an engineering prototype designed to test a feasibility assumption (38.6%)

- A/B or multivariate testing—a live production test where you compare the performance of 2+ options (32.6%)

- A one-question survey—a short survey typically embedded within a product (25%)

- Other (5.1%)—about half of these responses were customer interviews and the rest were specific types of prototype tests like comprehension tests, usability tests, concierge tests, etc.

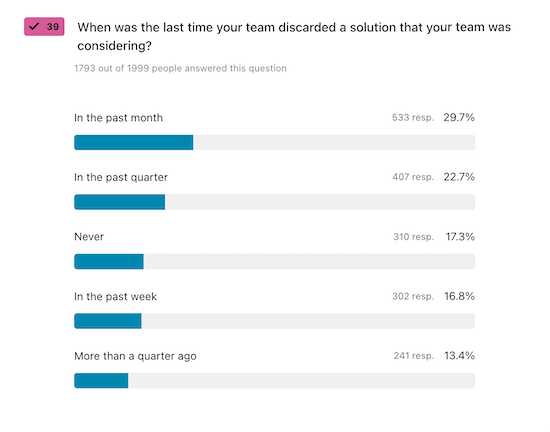

As I mentioned in the opening of this section, good discovery teams should be exploring many ideas and throwing many of them away. We asked all respondents, “When was the last time your team discarded a solution that your team was considering?”

I’m happy to see that a large percentage of teams said they discarded an idea in the past week or month.

Here are how the responses broke down:

- In the past week (16.8%)

- In the past month (29.7%)

- In the past quarter (22.7%)

- More than a quarter ago (13.4%)

- Never (17.3%)

I’m happy to see that 46.5% of respondents said they discarded an idea in the past week or month. I’m a little dismayed (although not surprised) that 30.7% of respondents either never discarded an idea or haven’t done so in more than a quarter.

Ideas are cheap. We know exploring many ideas is what gets us to good ideas. We need to be throwing out lots of ideas if we want to better serve our customers.

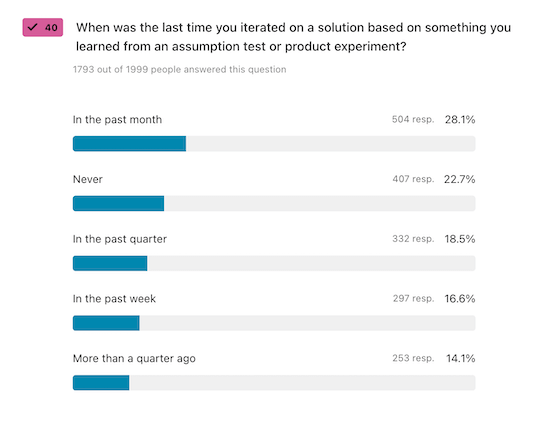

But assumption testing doesn’t just help us eliminate ideas, it also helps us evolve our mediocre ideas into good ideas. So we also asked, “When was the last time you iterated on a solution based on something you learned from an assumption test or product experiment?”

I’m glad to see that a large percentage of teams have iterated on their solutions in the past week or month, but dismayed that so many have either never iterated on an idea or haven’t done so for more than a quarter.

16.6% of respondents said “In the past week,” 28.1% said “In the past month,” 18.5% said “In the past quarter,” 14.1% said “More than a quarter ago,” and 22.7% said “Never.” Again, I’m glad to see that 44.7% of respondents said they iterated on their ideas in the past week or month. And I’m dismayed that 36.8% have either never iterated on an idea or it’s been more than a quarter.

This tells me that teams who are assumption testing are using their tests to both throw out bad ideas and to iterate on their mediocre ideas. However, it also tells me that a lot of teams still need help with this habit and that far too many teams are simply building their initial ideas without any evolution. It’s no surprise, then, why so many solutions simply don’t work.

Discovery Tools: Who is Using What

If I think back 15–20 years ago and consider what we had to do to connect with customers, test our ideas, and tabulate results, we have come a long way. Gone are the rooms with two-way mirrors. We no longer spend $30,000 to rent a facility to run a single usability study. We aren’t limited to recruiting participants in our nearby geographic region.

Instead, we have access to amazing discovery tools that help us recruit participants, conduct interviews around the world, launch in-product surveys, design unmoderated prototype tests, and so much more.

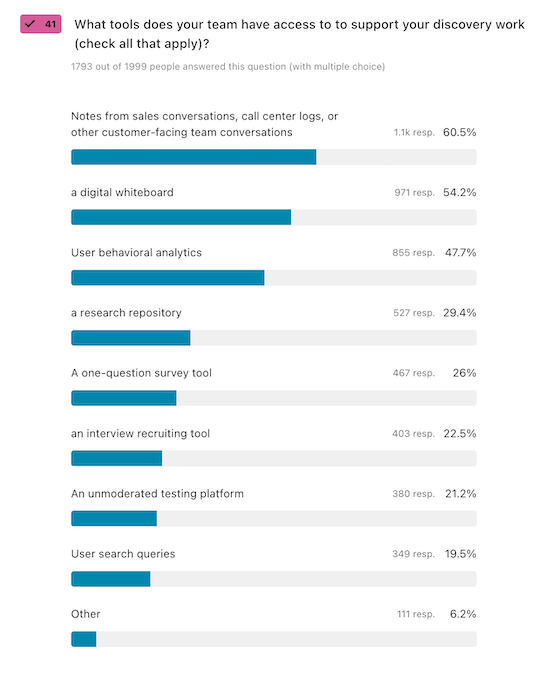

We wanted to learn who was taking advantage of these tools. So we asked, “What tools does your team have access to to support your discovery work? (check all that apply)”

Product teams have more tools than ever at their disposal to support their discovery work.

Here’s what respondents said they have access to:

- Notes from sales conversations, call center logs, or other customer-facing communications (60.5%)

- A digital whiteboard (54.2%)

- User behavioral analytics (47.7%)

- A research repository (29.4%)

- A one-question survey tool (26%)

- An interview recruiting tool (22.5%)

- An unmoderated testing platform (21.2%)

- User search queries (19.5%)

- Other (6.2%)

Over 50% of the “Other” responses were “none of the above.” I should have added that as an option. Other tools that came up under “Other” included heat maps, long-form survey tools, design tools like Figma and InVision, and Google.

I am surprised to see digital whiteboards have such widespread adoption. This is a testament to Miro and Mural for really building this market over the last few years. I was surprised and dismayed to see that fewer than half of the respondents had access to user behavioral analytics and less than 20% had access to search queries.

I’d love to see the market for all of these tools continue to grow. They really do help us shorten our discovery cycles and that’s better for everyone.

What’s Next?

As I wrote in the first post about this survey, I had two questions I wanted to answer with this survey:

- how many people were adopting each of the continuous discovery habits that I outlined in my book.

- if teams with better habits were more likely to have success than teams who haven’t developed their habits.

We’ve tackled the first question in this post. It is clear that many teams are working on adopting the different discovery habits. And I hope to see even more progress next year.

In future posts, I’ll dive into the second question. I have a series of hypotheses that I outlined when designing the survey that I’ll evaluate so that we can get a better idea of how different habits impact team success. If you don’t want to miss those posts, be sure to subscribe below.

The post Insights from the CDH Benchmark Survey: How Are Teams Adopting Discovery Habits? appeared first on Product Talk.

Insights from the CDH Benchmark Survey: How Are Teams Adopting Discovery Habits? was first posted on March 1, 2023 at 6:00 am.

©2022 "Product Talk". Use of this feed is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this article in your feed reader, then the site is guilty of copyright infringement. Please let us know at support@producttalk.org.