“It’s an open secret that every company is on fire” says Kintaba co-founder John Egan. “At any given moment something is going horribly wrong in a way that it has never gone wrong before.” Code failure downtimes, server outages, and hack attacks plague engineering teams. Yet the tools for waking up the right employees, assembling a team to fix the problem, and doing a post-mortem to assess how to prevent it from happening again can be as chaotic as the crisis itself.

Text messages, Slack channels, task managers, and Google Docs aren’t sufficient for actually learning from mistakes. Alerting systems like PagerDuty focus on the rapid response, but not the educational process in the aftermath. Finally there’s a more holistic solution to incident response with today’s launch of Kintaba.

The Kintaba team experienced these pains first hand while working at Facebook after Egan and Zac Morris’ Y Combinator-backed data transfer startup Caffeinated Mind was acqui-hired in 2012. Years later when they tried to build a blockchain startup and the whole stack was constantly in flames, they longed for a better incident alert tool. So they built one themselves and named it after the Japanese art of Kintsugi, where gold is used to fill in cracked pottery “which teaches us to embrace the imperfect and to value the repaired” Egan says.

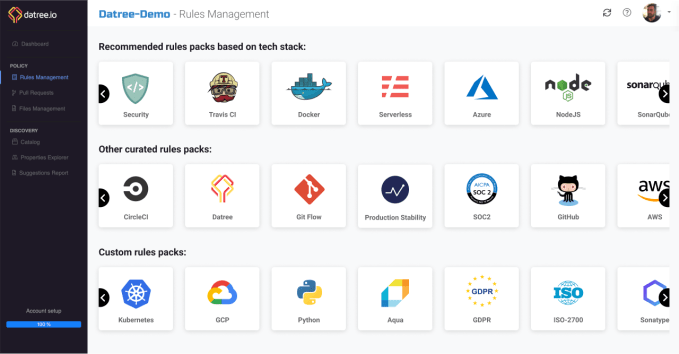

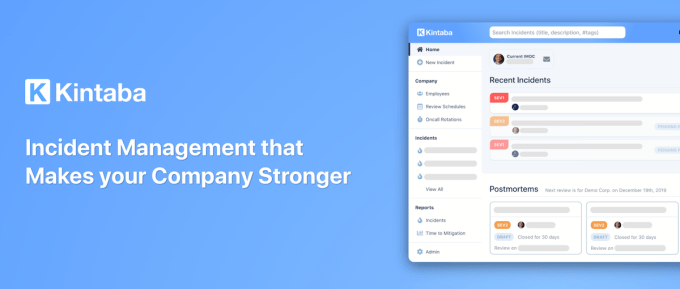

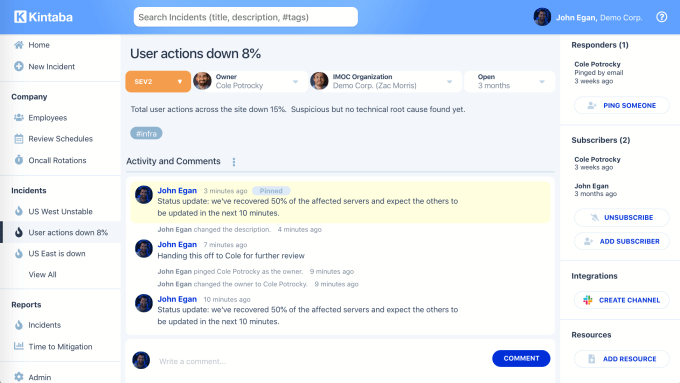

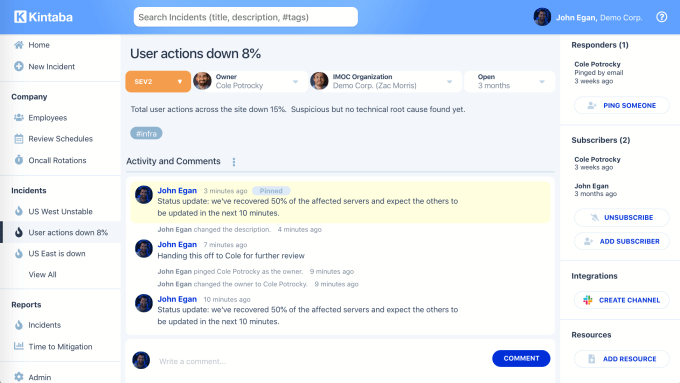

With today’s launch, Kintaba offers a clear dashboard where everyone in the company can see what major problems have cropped up, plus who’s responding and how. Kintaba’s live activity log and collaboration space for responders let them debate and analyze their mitigation moves. It integrates with Slack, and lets team members subscribe to different levels of alerts or search through issues with categorized hashtags.

“The ability to turn catastrophes into opportunities is one of the biggest differentiating factors between successful and unsuccessful teams and companies” says Egan. That’s why Kintaba doesn’t stop when your outage does.

Kintaba Founders (from left): John Egan Zac Morris Cole Potrocky

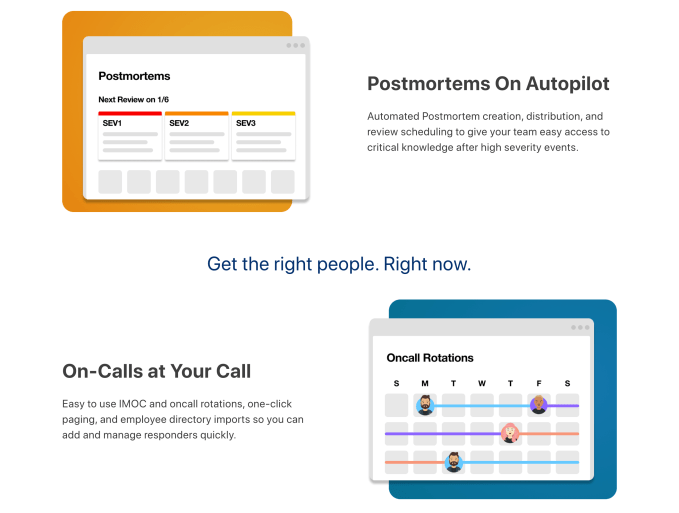

As the fire gets contained, Kintaba provides a rich text editor connected to its dashboard for quickly constructing a post-mortem of what went wrong, why, what fixes were tried, what worked, and how to safeguard systems for the future. Its automated scheduling assistant helps teams plan meetings to internalize the post-mortem.

Kintaba’s well-pedigreed team and their approach to an unsexy but critical software-as-a-service attracted $2.25 million in funding led by New York’s FirstMark Capital.

“All these features add up to Kintaba taking away all the annoying administrative overhead and organization that comes with running a successful modern incident management practice” says Egan, “so you can focus on fixing the big issues and learning from the experience.”

Egan, Morris and Cole Potrocky met while working at Facebook, which is known for spawning other enterprise productivity startups based on its top-notch internal tools. Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz built a task management system to reduce how many meetings he had to hold, then left to turn that into Asana which filed to go public this week.

The trio had been working on internal communication and engineering tools as well as the procedures for employing them. “We saw first hand working at companies like Facebook how powerful those practices can be and wanted to make them easier for anyone to implement without having to stitch a bunch of tools together” Egan tells me. He stuck around to co-found Facebook’ enterprise collaboration suite Workplace while Potrocky built engineering architecture there and Morris became a mobile security lead at Uber.

Like many blockchain projects, Kintaba’s predecessor, crypto collectibles wallet Vault, proved an engineering nightmare without clear product market fit. So the team ditched it, pivoted to build out the internal alerting tool they’d been tinkering with. That origin story sounds a lot like Slack’s, which began as a gaming company that pivoted to turn its internal chat tool into a business.

So what’s the difference between Kintaba and just using Slack and email or a monitoring tool like PagerDuty, Splunk’s VictorOps, or Atlassian’s OpsGenie? Here’s how Egan breaks a sit downtime situation handled with Kintaba:

“You’re on call and your pager is blowing up because all your servers have stopped serving data. You’re overwhelmed and the root cause could be any of the multitude of systems sending you alerts. With Kintaba, you aren’t left to fend for yourself. You declare an incident with high severity and the system creates a collaborative space that automatically adds an experienced IMOC (incident manager on call) along with other relevant on calls. Kintaba also posts in a company-wide incident Slack channel. Now you can work together to solve the problem right inside the incident’s collaborative space or in Slack while simultaneously keeping stakeholders updated by directing them to the Kintaba incident page instead of sending out update emails. Interested parties can get quick info from the stickied comments and #tags. Once the incident is resolved, Kintaba helps you write a postmortem of what went wrong, how it was fixed, and what will be done to prevent it from happening. Kintaba then automatically distributes the postmortem and sets up an incident review on your calendar.”

Essentially, instead of having one employee panicking about what to do until the team struggles to coordinate across a bunch of fragmented messaging threads, a smoother incident reporting process and all the discussion happens in Kintaba. And if there’s a security breach that a non-engineer notices, they can launch a Kintaba alert and assemble the legal and PR team to help too.

Alternatively, Egan describes the downtime fiascos he’d experience without Kintaba like this:

The on call has to start waking up their management chain to try and figure out who needs to be involved. The team maybe throws a Slack channel together but since there’s no common high severity incident management system and so many teams are affected by the downtime, other teams are also throwing slack channels together, email threads are happening all over the place, and multiple groups of people are trying to solve the problem at once. Engineers begin stepping all over each other and sales teams start emailing managers demanding to know what’s happening. Once the problem is solved, no one thinks to write up a postmortem and even if they do it only gets distributed to a few people and isn’t saved outside that email chain. Managers blame each other and point fingers at people instead of taking a level headed approach to reviewing the process that led to the failure. In short: panic, thrash, and poor communication.

While monitoring apps like PagerDuty can do a good job of indicating there’s a problem, they’re weaker at the collaborative resolution and post-mortem process, and designed just for engineers rather than everyone like Kintaba. Egan says “It’s kind of like comparing the difference between the warning lights on a piece of machinery and the big red emergency button on a factory floor. We’re the big red button . . . That also means you don’t have to rip out PagerDuty to use Kintaba” since it can be the trigger that starts the Kintaba flow.

Still, Kintaba will have to prove that it’s so much better than a shared Google Doc, an adequate replacement for monitoring solutions, or a necessary add-on that companies should pay $12 per user per month. PagerDuty’s deeper technical focus helped it go public a year ago, though it’s fallen about 60% since to a market cap of $1.75 billion. Still, customers like Dropbox, Zoom, and Vodafone rely on its SMS incident alerts, while Kintaba’s integration with Slack might not be enough to rouse coders from their slumber when something catches fire.

Still, Kintaba will have to prove that it’s so much better than a shared Google Doc, an adequate replacement for monitoring solutions, or a necessary add-on that companies should pay $12 per user per month. PagerDuty’s deeper technical focus helped it go public a year ago, though it’s fallen about 60% since to a market cap of $1.75 billion. Still, customers like Dropbox, Zoom, and Vodafone rely on its SMS incident alerts, while Kintaba’s integration with Slack might not be enough to rouse coders from their slumber when something catches fire.

If Kintaba can succeed in incident resolution with today’s launch, the four-person team sees adjacent markets in task prioritization, knowledge sharing, observability, and team collaboration, though those would pit it against some massive rivals. If it can’t, perhaps Slack or Microsoft Teams could be suitable soft landings for Kintaba, bringing more structured systems for dealing with major screwups to their communication platforms.

When asked why he wanted to build a legacy atop software that might seem a bit boring on the surface, Egan concluded that “Companies using Kintaba should be learning faster than their competitors . . . Everyone deserves to work within a culture that grows stronger through failure.”

Still, Kintaba will have to prove that it’s so much better than a shared Google Doc, an adequate replacement for monitoring solutions, or a necessary add-on that companies should pay $12 per user per month. PagerDuty’s deeper technical focus helped it go public a year ago, though it’s fallen about 60% since to a market cap of $1.75 billion. Still, customers like Dropbox, Zoom, and Vodafone rely on its SMS incident alerts, while Kintaba’s integration with Slack might not be enough to rouse coders from their slumber when something catches fire.

Still, Kintaba will have to prove that it’s so much better than a shared Google Doc, an adequate replacement for monitoring solutions, or a necessary add-on that companies should pay $12 per user per month. PagerDuty’s deeper technical focus helped it go public a year ago, though it’s fallen about 60% since to a market cap of $1.75 billion. Still, customers like Dropbox, Zoom, and Vodafone rely on its SMS incident alerts, while Kintaba’s integration with Slack might not be enough to rouse coders from their slumber when something catches fire.