Late Thursday the European Union secured agreement on the detail of a major competition reform that will see the most powerful, intermediating tech platforms subject to a set of up-front rules on how they can and cannot operate — with the threat of fines of up to 10% of global annual turnover should they breach requirements (or even 20% for repeat violations).

In three-way discussions between the European Council, parliament and Commission, which ran for around eight hours today, it was finally agreed that the Digital Markets Act (DMA) will apply to large companies providing “core platform services” — such as social networks or search engines — which have a market capitalisation of at least €75 billion or an annual turnover of €7.5 billion.

To be designated a so-called “gatekeepers”, and thus fall in scope of the DMA, companies must also have at least 45 million monthly end users in the EU and 10,000+ annual business users.

This puts US tech giants, including Apple, Google and Meta (Facebook), clearly in scope. While some less gigantic but still large homegrown European tech platforms — such as the music streaming platform Spotify — look set to avoid being subject to the regime as it stands. (Although other European platforms may already have — or gain — the scale to fall in scope.)

SMEs are generally excluded from being designated gatekeepers as the DMA is intended to take targeted aim at big tech.

The regulation has been years in the making — and is set to usher in a radically different ex ante regime for the most powerful tech platforms in contrast to the after-the-fact antitrust enforcement certain giants have largely been able to shrug off to date, with no discernible impact to marketshare.

Frustration with flagship EU competition investigations and enforcements against tech giants like Google — and widespread concern over the need to reboot tipped digital markets and restore the possibility of vibrant competition — have been core driving forces for the bloc’s lawmakers.

Commenting in a statement Andreas Schwab, the European Parliament’s Rapporteur for the file, said: “The agreement ushers in a new era of tech regulation worldwide. The Digital Markets Act puts an end to the ever-increasing dominance of Big Tech companies. From now on, they must show that they also allow for fair competition on the internet. The new rules will help enforce that basic principle. Europe is thus ensuring more competition, more innovation and more choice for users.”

In another supporting statement, Cédric O, French minister of state with responsibility for digital, added: “The European Union has had to impose record fines over the past 10 years for certain harmful business practices by very large digital players. The DMA will directly ban these practices and create a fairer and more competitive economic space for new players and European businesses. These rules are key to stimulating and unlocking digital markets, enhancing consumer choice, enabling better value sharing in the digital economy and boosting innovation. The European Union is the first to take such decisive action in this regard and I hope that others will join us soon.”

Key requirements agreed by the EU’s co-legislators include interoperability for messaging platforms, meaning smaller platforms will be able to request that dominant gatekeeper services open up on request and enable their users to be able to exchange messages, send files or make video calls across messaging apps, expanding choice and countering the typical social platform network effects that create innovation-chilling service lock in.

That could be hugely significant in empowering consumers who object to the policies of a giant like Meta, which owns Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp, but feel unable to switch to a rival since their social graph is held by the gatekeeper to actually leave without having to give up the ability to message their friends.

There had been some debate over whether messaging interoperability would survive the trilogues. It has — although group messaging interoperability is set to be phased in over a longer period than one-to-one messaging.

Speaking to TechCrunch ahead of today’s fourth and final trilogue, Schwab, emphasized the importance of messaging interoperability provisions.

“The Parliament has always been clear that interoperability for messaging has to come,” he told us. “It will come — at the same time, it also has to be secure. If the Telecoms Regulators say it is not possible to deliver end-to-end encrypted group chats within the next nine months, then it will come as soon as it is possible, there will be no doubt about that.”

Per Schwab, messenger services that are subject to the interoperability requirement will have to open up their APIs for competitors to provide interoperable messaging for basic features — with the requirement intentionally asymmetrical, meaning that smaller messaging services which are not in the scope of the DMA will not be required to open up to gatekeepers but can themselves connect into Big Tech.

“The first basic messaging features will be user-to-user messages, video and voice calls, as well as basic file transfer (photos, videos), and then over time, more features such as group chats will come,” noted Schwab, adding: “Everything must be end-to-end encrypted.”

Interoperability for social media services has been put on ice for now — with the EU co-legislators agreeing that such provisions will be assessed in the future.

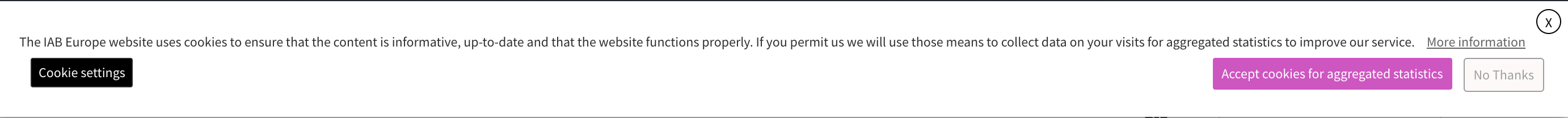

In another important decision which could have major ramifications for dominant digital business models, the parliament managed to keep an amendment to an earlier version of the proposal — which means that explicit consent from users will be required for a gatekeeper to combine personal data for targeted advertising.

“Data combination and cross use will only be possible with explicit consent,” said Schwab. “This is especially true for the purpose of advertising and also applies to combination with third party data (e.g. Facebook with third parties). This means more control for users whether they want to be tracked across devices/services, even outside of the networks of Big Tech (hence the third party data), and whether they want to receive tracking ads.”

“Lastly, to avoid consent fatigue, Parliament will limit how many times Gatekeepers can ask again for consent if you refused it or withdrawn consent to these practices: Once per year. This has been very important to me — otherwise, consent would be meaningless if gatekeeper can simply spam users until they give in,” he added.

Another parliament-backed requirement which survived the trilogue negotiations is a stipulation that users should be able to freely choose their browser, virtual assistants or search engines when such a service is operated by a gatekeeper — meaning choice screens, not pre-selected defaults, will be the new norm in those areas for in scope platforms.

Although email — another often bundled choice which European end-to-end encrypted email service ProtonMail had been arguing should also get a choice screen — does not appear to have been included, with lawmakers narrowing this down to “the most important software”, as the Council put it.

Other obligations on gatekeepers in the agreed text include requirements to:

- ensure that users have the right to unsubscribe from core platform services under similar conditions to subscription

- allow app developers fair access to the supplementary functionalities of smartphones (e.g. NFC chip)

- give sellers access to their marketing or advertising performance data on the platform

- inform the European Commission of their acquisitions and mergers

And among the restrictions are stipulations that gatekeepers cannot:

- rank their own products or services higher than those of others (aka a ban on self-preferencing)

- reuse private data collected during a service for the purposes of another service

- establish unfair conditions for business users

- pre-install certain software applications

- require app developers to use certain services (e.g. payment systems or identity providers) in order to be listed in app stores

The Commission will be solely responsible for enforcing the DMA — and it will have some leeway over whether to immediately crack down on duty-breaching tech giants, with the text allowing the possibility of engaging in regulatory dialogue to ensure gatekeepers have a clear understanding of the rules (i.e. rather than reaching straight for a chunky penalty).

Today’s agreement on a provisional text of the DMA marks almost the last milestone on a multi-year journey towards the DMA proposal becoming law. But there are still a few hoops for European lawmakers to jump through.

It’s still pending approval of the finalized legal text by the Parliament and Council (but getting consensus agreement in the first place is typically the far harder ask). Then, after that final vote, the text will be published in the EU’s official journey and the regulation will come into force 20 days later — with six months allowed for Member States to implement it in national legislation.

EU commissioners will be holding a series of — doubtless very jubilant — briefings tomorrow to flesh out the finer detail of what’s been agreed so stay tuned for more analysis…

member

member