Breaking up tech giants should be a measure of last resort, the European Union’s competition commissioner, Margrethe Vestager, has suggested.

“To break up a company, to break up private property would be very far reaching and you would need to have a very strong case that it would produce better results for consumers in the marketplace than what you could do with more mainstream tools,” she warned this weekend, speaking in a SXSW interview with Recode’s Kara Swisher. “We’re dealing with private property. Businesses that are built and invested in and become successful because of their innovation.”

Vestager has built a reputation for being feared by tech giants, thanks to a number of major (and often expensive) interventions since she took up the Commission antitrust brief in 2014, with still one big outstanding investigation hanging over Google.

But while opposition politicians in many Western markets — including high profile would-be U.S. presidential candidates — are now competing on sounding tough on tech, the European commissioner advocates taking a scalpel to data streams rather than wielding a break-up hammer to smash market-skewing tech giants.

“When it comes to the very far reaching proposal to split up companies, for us, from a European perspective, that would be a measure of last resort,” she said. “What we do now, we do the antitrust cases, misuse of dominant position, the tying of products, the self-promotion, the demotion of others, to see if that approach will correct and change the marketplace to make it a fair place where there’s no misuse of dominant position but where smaller competitors can have a fair go. Because they may be the next big one, the next one with the greatest idea for consumers.”

She also pointed to an agreement last month, between key European political institutions on regulating online platform transparency, as an example of the kind of fairness-focused intervention she believes can work to counter market imbalance.

The bread and butter work regulators should be focused on where big tech is concerned are things like digital sector enquiries and hearings to examine how markets are operating in detail, she suggested — using careful scrutiny to inform and shape intelligent, data-led interventions.

Albeit ‘break up Google’ clearly makes for a punchier political soundbite.

Vestager is, however, in the final months of her term as antitrust chief — with the Commission due to turn over this year. Her time at the antitrust helm will end on November 1, she confirmed. (Though she remains, at least tentatively, on a shortlist of candidates who could be appointed the next European Commission president.)

The commissioner has spoken up before about regulating access to data as a more interesting option for controlling digital giants vs breaking them up.

And some European regulators appear to be moving in that direction already. Such the German Federal Cartel Office (FCO) which last month announced a decision against Facebook which aims to limit how it can use data from its own services. The FCO’s move has been couched as akin to an internal break up of the company, at the data level, without the tech giant having to be forced to separate and sell off business units like Instagram and WhatsApp.

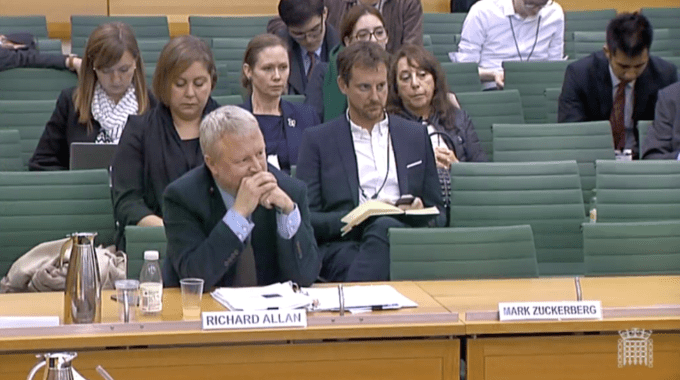

It’s perhaps not surprising, therefore, that Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg announced a massive plan to merge all three services at the technical level just last week — billing the switch to encrypted content but merged metadata as a ‘pro-privacy’ move, while clearly also intending to restructure his empire in a way that works against regulatory interventions that separate and control internal data flows at the product level.

The Competition Commission does not have a formal probe of Facebook or the social media sector open at this point but Vestager said her department does have its eye on how social media giants are using data.

“We’re sort of hoovering over social media, Facebook — how data’s being used in that respect,” she said, also flagging the preliminary work it’s doing looking into Amazon’s use of merchant data. (Also still not yet a formal probe.)

“The good thing is now the debate is really sort of taking off,” she added, of competition regulation generally. “When I’ve been visiting and speaking with people on The Hill previously, I’ve sensed a new sort of interest and curiosity as to what can competition achieve for you in a society. Because if you have fair competition then you have markets serving the citizen in our role as consumer and not the other way around.”

Asked whether she’s personally convinced by Facebook’s sudden ‘appreciation’ of privacy Vestager said if the announcement signifies a genuine change of philosophy and direction which leads to shifts in its business practices it would be good news for consumers.

Though she said she’s not simply taking Zuckerberg at his word at this point. “It may be a little far-reaching to assume the best,” she said politely when pushed by Swisher on whether she believed a sincere pivot is possible from a company with such a long privacy-hostile history.

Big tech, small tax

The interview also delved into the issue of big tech and the tiny amounts it pays in tax.

Reforming the global tax system so digital businesses pay a fair share vs traditional businesses is now “urgent” work to do, said Vestager — highlighting how the lack of a consensus position among EU Member States is pushing some countries to move forward with their own measures, given resistance to Commission proposals from other corners of the bloc.

France‘s push for a tax on tech giants this year is “absolutely necessary but very unfortunate”, Vestager said.

“When you do numbers that can be compared we see that digital businesses they would pay on average nine per cent [in taxes] where traditional businesses on average pay 23 per cent,” she continued. “Yet they’re in the same market for capital, for skilled employees, sometimes competing for the same customers. So obviously this is not fair.”

The Commission’s hope is that individual “pushes” from Member States frustrated by the current tax imbalance will generate momentum for “a European-wide way of doing things” — and therefore that any fragmentation of tax policies across the bloc will be short-lived.

She also she Europe is keen for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to “push forward for this” too, remarking: “Because we sense in the OECD that a number of places in the world take an interest also in the U.S. side of things.”

Is the better way to reset inequalities related to big tech and society achieved via reforming the tax system or are regulators doomed to have to keep fining them “into the next century”, wondered Swisher.

“You get a fine when you do something illegal. You pay your taxes to contribute to society where you do your business. These are two different things and we definitely need both,” responded Vestager. “But we cannot have a situation where some businesses do not contribute and the majority of businesses they do. Because it’s simply not fair in the marketplace or fair towards citizens if this continues.”

She also made short shrift of the favored big tech lobbyist line — to loudly claim privacy regulation helps big guys because it’s easier for them to fund compliance — by pointing out that Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation has “different brackets” and does not simply clobber big and small alike with the same requirements.

Of course small businesses “don’t have the same obligations as Google”, said Vestager.

“I’d say if they find it easy, I’d say they can do better,” she added, raising the much complained about consumer rights issue of consent vs inscrutable T&Cs.

“Because I still find that it’s quite tricky to understand what it is that you accept when you accept your terms and conditions. And I think it would be great if we as citizens could really say ‘oh this is what I am signing up to and I’m perfectly happy with that’.”

Though she admitted there’s still a way to go for European privacy rights to be fully functioning as intended — arguing it’s still too hard for individual consumers to exercise the rights they have in law.

“I know I own my data but I really do not know how to exercise that ownership,” she said. “How to allow for more people to have access to my data if I want to enable innovation, new market participants coming in. If that was done in large scale you could have an innovative input into the marketplace and we’re definitely not there yet,” she said.

Asked about the idea of taxing data flows as another possible means of clipping the wings of big tech Vestager pointed to early signs of an intermediate market spinning up in Europe to help individual extract value from what corporate entities are doing with their information. So not literally a tax on data flows but a way for consumers to claw back some of the value that’s being stripped from them.

“It’s still nascent in Europe but since now we have the rights that establishes your ownership of your data we see there is a beginning market development of intermediaries saying should I enable you yourself to monetize your data, so it’s not just the giants who monetize your data. So that maybe you get a sum every month reflecting how your data has been passed on,” she said. “That is one opportunity.”

She also said the Commission is looking at how to make sure “huge amounts of data will not be a barrier to entry in a marketplace” — or present a barrier to innovation for newcomers. The latter being key given how tech giants’ massive data pools are translating into a meaty advantage in AI R&D.

In another interesting exchange, Vestager suggested the convenience of voice interfaces presents an acute competition challenge — given how the tech could naturally concentrate market power via preferring quick-fire Q&A style interactions which don’t support offering lots of choice options.

“One of the things that is really mindboggling for us is how to have choice if you have voice,” she said, arguing that voice assistance dynamic doesn’t lend itself to multiple suggestions being offered every time a user asks a question. “So how to have competition when you have voice search?.. How would this change the marketplace and how would we deal with such a market? So this is what we’re trying to figure out.”

Again she suggested regulators are thinking about how data flows behind the scenes as a potential route to remedying interfaces that work against choice.

“We’re trying to figure out how access to data will change the marketplace,” she added. “Can you give a different access to data because the one who holds the data, also holds the resources for innovation. And we cannot rely on the big guys to be the innovative ones.”

Asked for her worst case scenario for tech 10 years hence, she said it would be to have “all of the technology but none of the societal positive oversight and direction”.

On the flip side, the best case would be for legislators to be “willing to take sufficient steps in taxation and in regulating access to data and fairness in the marketplace”.

“We would also need to see technology develop to have new players,” she emphasized. “Because we still need to see what will happen with quantum computing, what will happen with blockchain, what other uses are there for all if that new technology. Because I still think that it holds a lot of promise. But only if our democracy will give it direction. Then you will have a positive outcome.”

(@maxschrems)

(@maxschrems)