There is no question that the arrival of a fragmented and divided internet is now upon us. The “splinternet,” where cyberspace is controlled and regulated by different countries is no longer just a concept, but now a dangerous reality. With the future of the “World Wide Web” at stake, governments and advocates in support of a free and open internet have an obligation to stem the tide of authoritarian regimes isolating the web to control information and their populations.

Both China and Russia have been rapidly increasing their internet oversight, leading to increased digital authoritarianism. Earlier this month Russia announced a plan to disconnect the entire country from the internet to simulate an all-out cyberwar. And, last month China issued two new censorship rules, identifying 100 new categories of banned content and implementing mandatory reviews of all content posted on short video platforms.

While China and Russia may be two of the biggest internet disruptors, they are by no means the only ones. Cuban, Iranian and even Turkish politicians have begun pushing “information sovereignty,” a euphemism for replacing services provided by western internet companies with their own more limited but easier to control products. And a 2017 study found that numerous countries, including Saudi Arabia, Syria and Yemen have engaged in “substantial politically motivated filtering.”

This digital control has also spread beyond authoritarian regimes. Increasingly, there are more attempts to keep foreign nationals off certain web properties.

For example, digital content available to U.K. citizens via the BBC’s iPlayer is becoming increasingly unavailable to Germans. South Korea filters, censors and blocks news agencies belonging to North Korea. Never have so many governments, authoritarian and democratic, actively blocked internet access to their own nationals.

The consequences of the splinternet and digital authoritarianism stretch far beyond the populations of these individual countries.

Back in 2016, U.S. trade officials accused China’s Great Firewall of creating what foreign internet executives defined as a trade barrier. Through controlling the rules of the internet, the Chinese government has nurtured a trio of domestic internet giants, known as BAT (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent), who are all in lock step with the government’s ultra-strict regime.

The super-apps that these internet giants produce, such as WeChat, are built for censorship. The result? According to former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, “the Chinese Firewall will lead to two distinct internets. The U.S. will dominate the western internet and China will dominate the internet for all of Asia.”

Surprisingly, U.S. companies are helping to facilitate this splinternet.

Google had spent decades attempting to break into the Chinese market but had difficulty coexisting with the Chinese government’s strict censorship and collection of data, so much so that in March 2010, Google chose to pull its search engines and other services out of China. However now, in 2019, Google has completely changed its tune.

Google has made censorship allowances through an entirely different Chinese internet platform called project Dragonfly . Dragonfly is a censored version of Google’s Western search platform, with the key difference being that it blocks results for sensitive public queries.

Sundar Pichai, chief executive officer of Google Inc., sits before the start of a House Judiciary Committee hearing in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Tuesday, Dec. 11, 2018. Pichai backed privacy legislation and denied the company is politically biased, according to a transcript of testimony he plans to deliver. Photographer: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “people have the right to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

Drafted in 1948, this declaration reflects the sentiment felt following World War II, when people worked to prevent authoritarian propaganda and censorship from ever taking hold the way it once did. And, while these words were written over 70 years ago, well before the age of the internet, this declaration challenges the very concept of the splinternet and the undemocratic digital boundaries we see developing today.

As the web becomes more splintered and information more controlled across the globe, we risk the deterioration of democratic systems, the corruption of free markets and further cyber misinformation campaigns. We must act now to save a free and open internet from censorship and international maneuvering before history is bound to repeat itself.

BRUSSELS, BELGIUM – MAY 22: An Avaaz activist attends an anti-Facebook demonstration with cardboard cutouts of Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg, on which is written “Fix Fakebook”, in front of the Berlaymont, the EU Commission headquarter on May 22, 2018 in Brussels, Belgium. Avaaz.org is an international non-governmental cybermilitating organization, founded in 2007. Presenting itself as a “supranational democratic movement,” it says it empowers citizens around the world to mobilize on various international issues, such as human rights, corruption or poverty. (Photo by Thierry Monasse/Corbis via Getty Images)

The Ultimate Solution

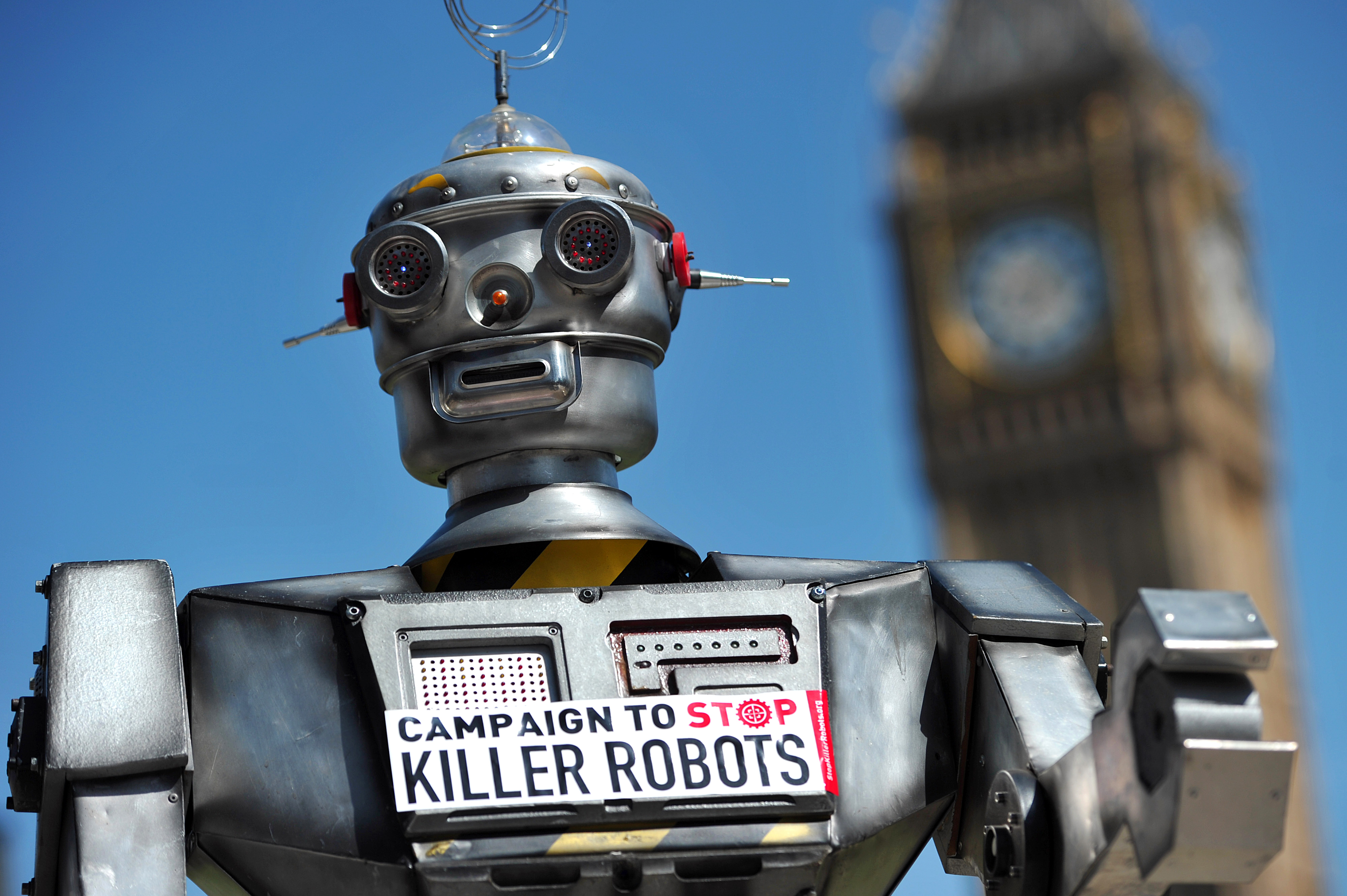

Similar to the UDHR drafted in 1948, in 2016, the United Nations declared “online freedom” to be a fundamental human right that must be protected. While not legally binding, the motion passed with consensus, and therefore the UN was provided limited power to endorse an open internet (OI) system. Through selectively applying pressure on governments who are not compliant, the UN can now enforce digital human rights standards.

The first step would be to implement a transparent monitoring system which ensures that the full resources of the internet, and ability to operate on it, are easily accessible to all citizens. Countries such as North Korea, China, Iran and Syria, who block websites and filter email plus social media communication, would be encouraged to improve through the imposition of incentives and consequences.

All countries would be ranked on their achievement of multiple positive factors including open standards, lack of censorship, and low barriers to internet entry. A three tier open internet ranking system would divide all nations into Free, Partly Free or Not Free. The ultimate goal would be to have all countries gradually migrate towards the Free category, allowing all citizens full information across the WWW, equally free and open without constraints.

The second step would be for the UN to align itself much more closely with the largest western internet companies. Together they could jointly assemble detailed reports on each government’s efforts towards censorship creep and government overreach. The global tech companies are keenly aware of which specific countries are applying pressure for censorship and the restriction of digital speech. Together, the UN and global tech firms would prove strong adversaries, protecting the citizens of the world. Every individual in every country deserves to know what is truly happening in the world.

The Free countries with an open internet, zero undue regulation or censorship would have a clear path to tremendous economic prosperity. Countries who remain in the Not Free tier, attempting to impose their self-serving political and social values would find themselves completely isolated, visibly violating digital human rights law.

This is not a hollow threat. A completely closed off splinternet will inevitably lead a country to isolation, low growth rates, and stagnation.