The global pandemic has cast a light on decades of cumulative efforts to manipulate and suppress voters, showing that the country is completely unprepared for any serious challenge to its elections system. There can be no more excuses: Every state must implement voting by mail in 2020 or be prepared to admit it is deliberately sabotaging its own elections. (And for once, tech might be able to help.)

To visualize how serious this problem is, one has only to imagine what would happen if quarantine measures like this spring’s were to happen in the fall — and considering experts predict a second wave in that period, this is very much a possibility.

If lockdown measures were being intensified and extended not on May 3rd, but November 3rd, how would the election proceed?

The answer is: it wouldn’t.

There would be no real election because so few people in the country would be able to legally and safely vote. This is hardly speculative: We have seen it happen in states where, for lack of any other option, people had to risk their lives, breaking quarantine to vote in person. Naturally it was the most vulnerable groups — people of color, immigrants, the poor and so on — who were most affected. The absurdity of a state requiring voters to gather in large groups while forbidding people to gather in large groups is palpable.

With this problem scaled to national levels, the entire electoral process would be derailed, and the ensuing chaos would be taken advantage of by all and sundry for their own purposes — something we see happening in practically every election.

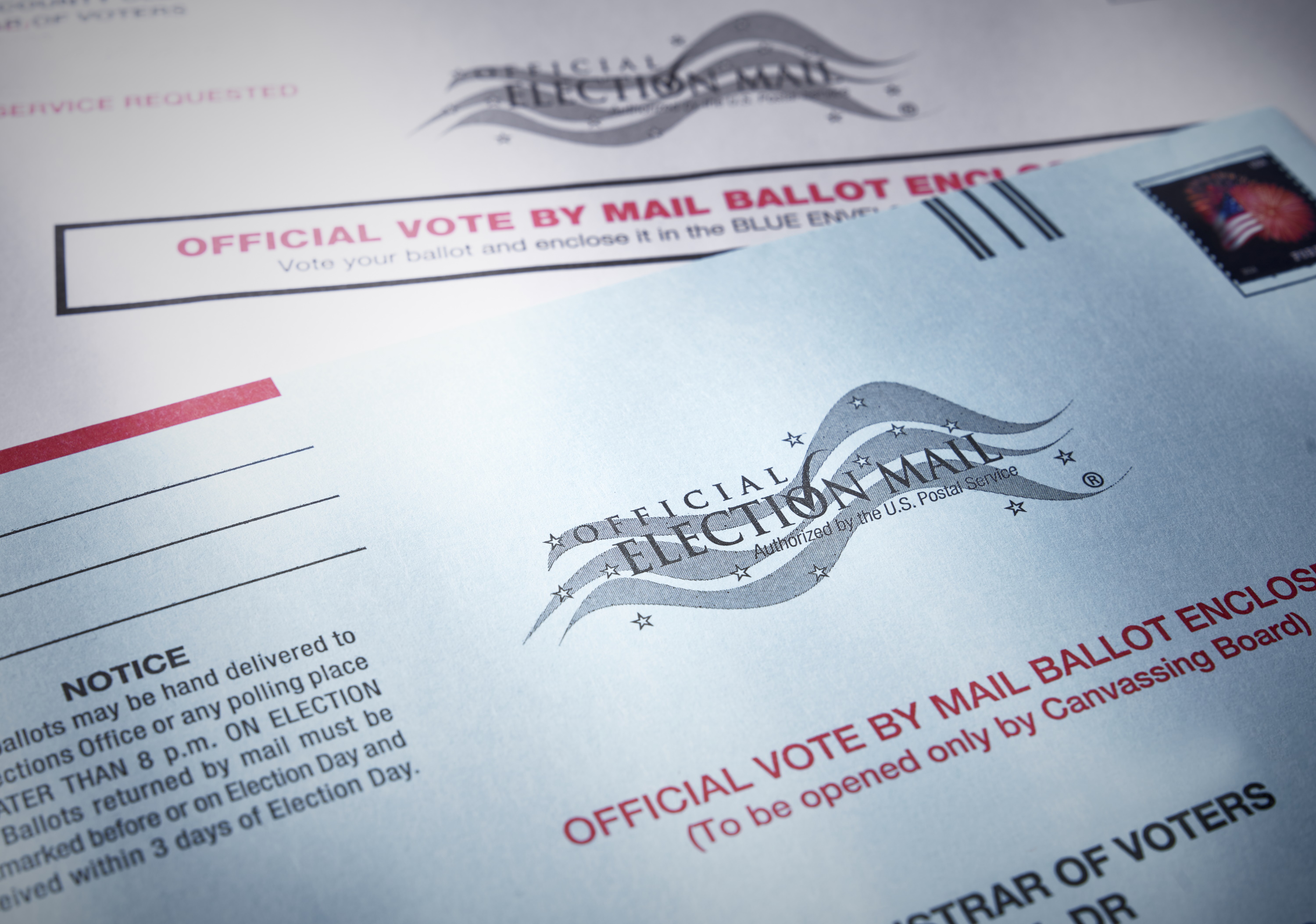

For the 2020 election, if any elections official in this country claims to value the voters for which they are responsible, voting by mail is the only way to enable every citizen to register and vote securely and remotely. Anything less can only be considered deliberate obstruction, or at best willful negligence, of the electoral process.

Image Credits: Bill Oxford / iStock Unreleased / Getty Images

There’s a fair amount of talk about apps, online portals and other avenues, and these may figure later, but mail is the only method guaranteed right now to securely serve every address and person, providing the fundamental fabric of connectivity that is absolutely necessary to universally accessible voting.

Hand-wringing about fraud, lost ballots and other issues with voting by mail is deliberate, politically motivated FUD (and you can expect a lot of it over the next few months). States where voting by mail is the standard report no such issues; on the contrary, they have high turnout and few problems because it is simple, effective and secure. As far as risk is concerned, there is absolutely no comparison to the widespread and well-documented process and security issues with touchscreen voting systems, even before you bring in the enormous public health concerns of using those methods during a pandemic.

Federal law requires that troops around the world, among others unable to vote in person, are able to request and submit their ballots by mail. That this is the preferred method for voting in combat zones is practically all the endorsement such a system needs. That the president votes by mail is just the cherry on top.

Fear of voters

So why hasn’t voting by mail been adopted more widely? The same reason we have gerrymandered districts: Politicians have manipulated the electoral process for decades in order to stack the deck in their favor. While gerrymandering has been employed with great (and deplorable) effect by both Democratic and Republican officials, voter suppression is employed overwhelmingly by the political right.

While this is certainly a politically charged statement, it’s not really a matter of opinion. The demographics of the voting public are such that as the proportion of the population that votes grows, the aggregate position begins to lean leftward. This happens for a variety of reasons, but the result is that limiting who votes benefits conservatives more than liberals. (I am not so naive to think that if it were the other way around, Democrats would altogether abstain from the practice, but that isn’t the case.)

This is not a new complaint. Deliberate voter suppression goes back a century and more. Nor is the practice equally distributed. For one thing, white, well-off, urban areas are more likely to have effective and modern voting systems and laws.

This is not only because those areas are generally the first to receive all good things, but because voter suppression has been aimed specifically at people of color, immigrants, the poor and so on. Again, this is no longer a controversial or even particularly partisan statement; it has been admitted to by politicians and strategists at every level — including, quite recently, by the president: “They had things, levels of voting that if you’d ever agreed to it, you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.”

When voting by mail was merely a convenient, effective alternative to voting in person, it was fairly easy to speak against it. Now, however, voting by mail is increasingly looking like the only possible method to accomplish an election.

Again, think of how we would vote during a stay-at-home order. Using only today’s methods would be dangerous, chaotic and generally an ineffective way to ask the population at large who they want to lead their city, state and country.

That is no way to conduct an election. Therefore, we currently have no way to conduct a national election. Voting by mail is the only method that can realistically be rolled out to accomplish an effective election in 2020.

Disunited states

Because elections are run by state authorities, voting methods and laws vary widely between them. The quickest way to a nationwide vote-by-mail system would use federal funding and authority, but even if states were in favor of this (they won’t be, as it is an encroachment on their authority), Washington is not. The possibility of a bill implementing universal voting by mail passing the House, Senate and the president’s desk by November is, sadly, remote.

Which is not to say that no one in D.C. is not trying it:

This means it’s down to the states — not great news, considering it is at the state level that voting rights have been eroded and voter suppression enshrined in policy.

The only hope we have is for state authorities to recognize that the 2020 presidential election will be a closely watched litmus test for competence and corruption that will haunt them for years. It’s one thing to put your finger on the scale under normal circumstances. It’s quite another to author a high-profile electoral failure in an election few doubt will be one of the most consequential in American history — especially if that failure was manifestly preventable.

And we know it is preventable because due to federal voting rights laws, every state already has some form of accessible, mail-in or absentee voting. This is not a matter of inventing a new system from scratch, but scaling existing, proven systems in ways already demonstrated and verified over decades. Several states, for instance, have simply announced that all voters will get absentee ballots or applications sent unrequested to their homes. No one said it would be easy, but the first step — committing — is at least simple.

It will be obvious in a few months which state authorities actually care about the vote and which see it as just another instrument to manipulate in order to retain and accrue power. The actions taken in the run-up to this election will be remembered for a long time. As for the federal government interfering with states’ prerogative to run their own elections — that’s a violation of states’ rights that I expect will encounter strong bipartisan opposition.

How tech can help without hindering

The tech world will want to aid in this cause out of several motives, but the simple truth is there’s no way a technological solution can be developed and deployed by November. And not only is it infeasible, but there is serious political opposition to online voting systems to be widely deployed. The idea is a non-starter for this election and probably the next.

Rather than trying, Monolith-style, to evolve voting to the next phase by taking on the whole thing tip to tail, tech should be providing support structures via uniquely digital tools that complement rather than replace effective voting systems.

For example, there is the possibility, however remote, that a mailed ballot will be intercepted by some adversary and modified, shredded, selectively deposited, or what have you. No large-scale fraud has ever been perpetrated, despite what opponents of voting by mail might say. States developed preventative solutions long ago, like secure ballot boxes placed around the city and tamper-evident envelopes.

But end to end security is something at which the tech sector excels, and moreover recent advances make a digitally augmented voting process achievable. And there’s plenty of room for competition and commercial involvement, which sweetens the pot.

Here’s a way that commonplace tech could be deployed to make voting by mail even more secure and convenient.

Imagine a mail-in ballot of the ordinary fill-in-the-bubble type. Once a person makes their selections, they take a picture of the ballot in a dedicated, completely offline app. Via fairly elementary image analysis nearly any phone can now perform, the votes can be detected and tabulated, verified by the voter, then hashed with a unique voter sheet ID into a code short enough to be written down.

The ballot is mailed and (let us say for now) received. When it is processed, the same hash is calculated by the machine reader and placed on an easily accessible list. A voter can check that their vote was tabulated and correctly recorded by entering their hash into a website — which itself reveals nothing about their vote or identity.

What if something goes wrong? Say the ballot is lost. In that case the voter has a record of their vote in both image and physical form (mail-in ballots have little tear-off tabs you keep) and can pursue this issue. The same database that lets them verify their vote was correct will allow them to see if their vote was never cast. If it was interfered with or damaged and the selections differ from what the voter already verified, the hash will differ, and the voter can prove this with the evidence they have — again, entirely offline and with no private information exposed.

This example system only works because smartphones are now so common, and because it is now trivial to process an image quickly and accurately offline. But importantly, the digital aspect only addresses shortcomings of the mail-in system rather than being central to it. You vote with only a ballpoint pen, as simply as possible — but if you want to be sure, you may choose to employ the latest technology to track your vote.

A system like this may not make it in time for the 2020 election, but voting by mail can and must if there is to be an election at all.

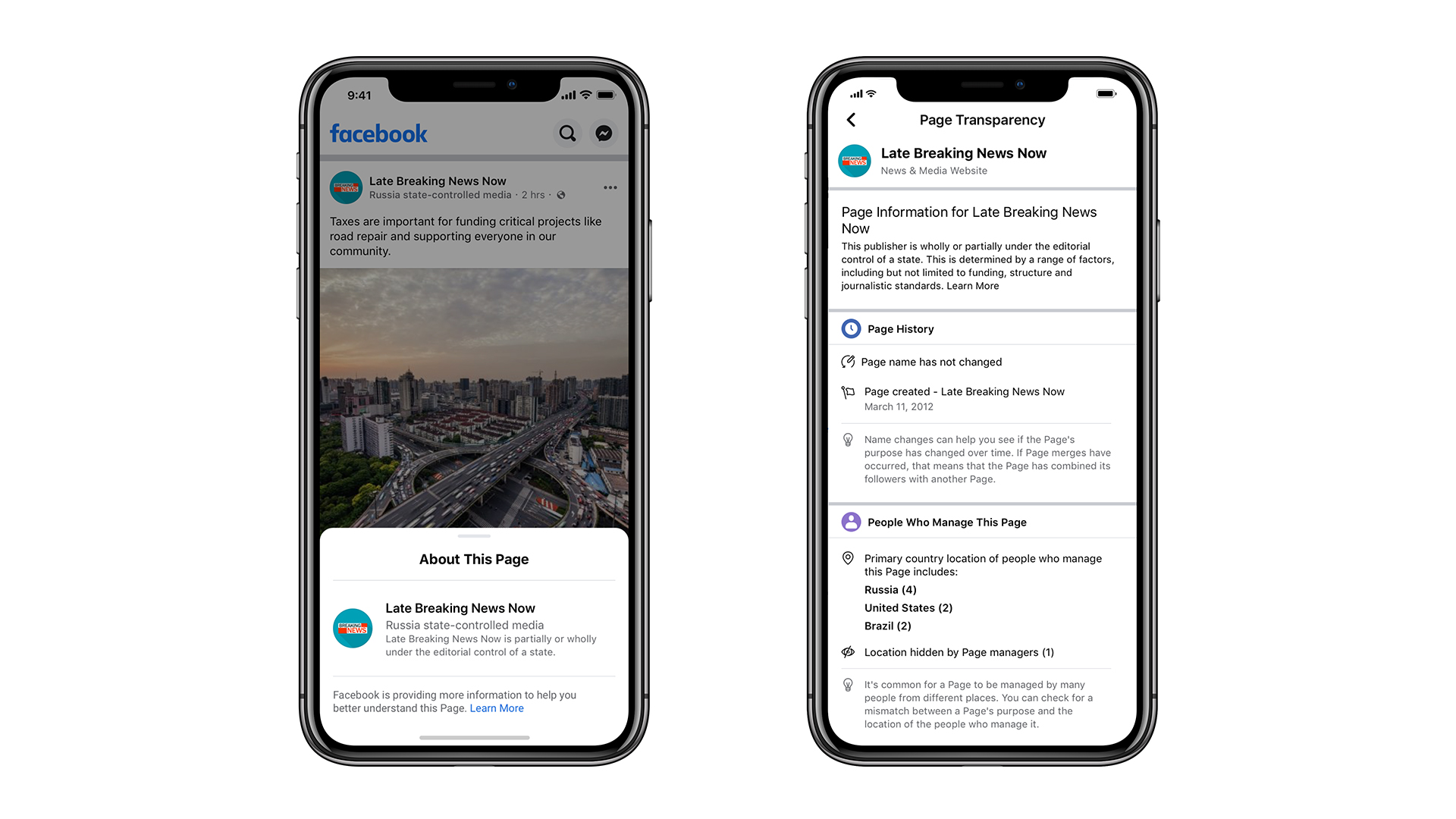

The warning reads: “This publisher is wholly or partially under the editorial control of a state. This is determined by a range of factors, including but not limited to funding, structure and journalistic standards.”

The warning reads: “This publisher is wholly or partially under the editorial control of a state. This is determined by a range of factors, including but not limited to funding, structure and journalistic standards.”