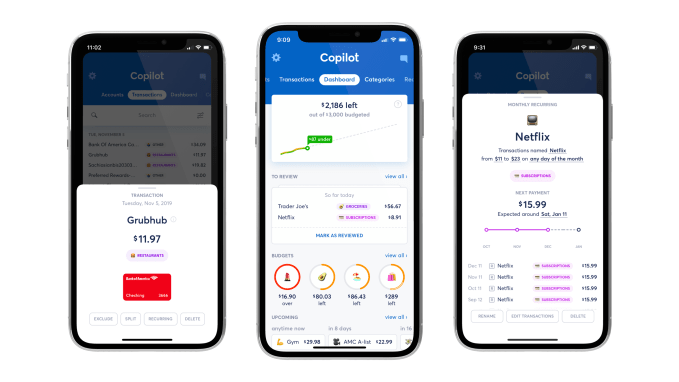

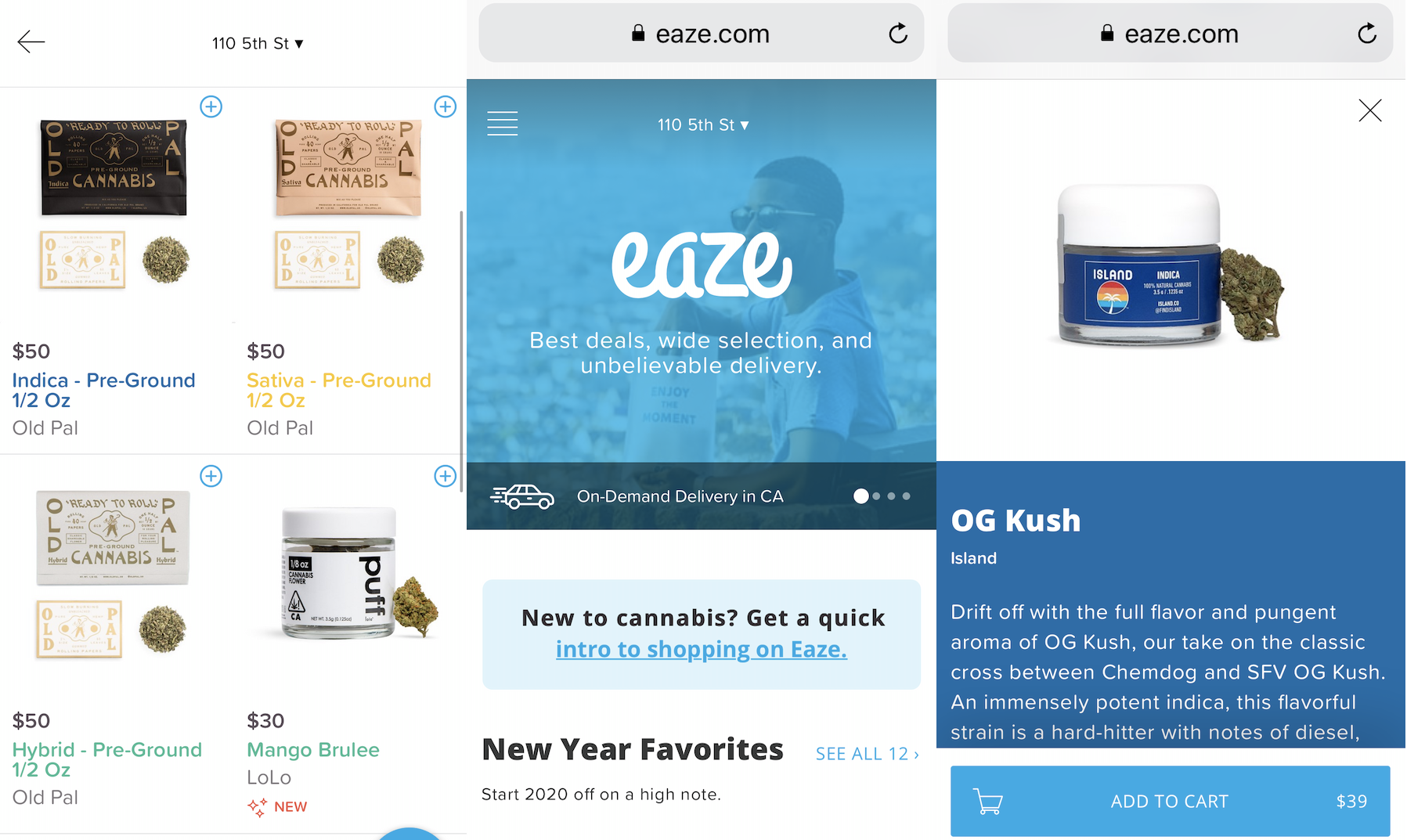

The first cannabis startup to raise big money in Silicon Valley is in danger of burning out. TechCrunch has learned that pot delivery middleman Eaze has seen unannounced layoffs, and its depleted cash reserves threaten its ability to make payroll or settle its AWS bill. Eaze was forced to raise a bridge round to keep the lights on as it prepares to attempt major pivot to ‘touching the plant’ by selling its own marijuana brands through its own depots.

If Eaze fails, it could highlight serious growing pains amid the ‘green rush’ of startups into the marijuana business.

Eaze, the startup backed by some $166 million in funding that once positioned itself as the “Uber of pot” — a marketplace selling pot and other cannabis products from dispensaries and delivering it to customers — has recently closed a $15 million bridge round, according to multiple source. The fund was meant to keep the lights on as Eaze struggles to raise its next round of funding amid problems with making decent margins on its current business model, lawsuits, payment processing issues, and internal disorganization.

An Eaze spokesperson confirmed that the company is low on cash. Sources tell us that the company, which laid off some 30 people last summer, is preparing another round of cuts in the meantime. The spokesperson refused to discuss personnel issues but noted that there have been layoffs at many late stage startups as investors want to see companies cut costs and become more efficient.

From what we understand, Eaze is currently trying to raise a $35 million Series D round according to its pitch deck. The $15 million bridge round came from unnamed current investors. (Previous backers of the company include 500 Startups, DCM Ventures, Slow Ventures, Great Oaks, FJ Labs, the Winklevoss brothers, and a number of others.) Originally, Eaze had tried to raise a $50 million Series D, but the investor that was looking at the deal, Athos Capital, is said to have walked away at the eleventh hour.

Eaze is going into the fundraising with an enterprise value of $388 million, according to company documents reviewed by TechCrunch. It’s not clear what valuation it’s aiming for in the next round.

An Eaze spokesperson declined to discuss fundraising efforts but told TechCrunch, “The company is going through a very important transition right now, moving to becoming a plant-touching company through acquisitions of former retail partners that will hopefully allow us to more efficiently run the business and continue to provide good service to customers.

Desperate to grow margins

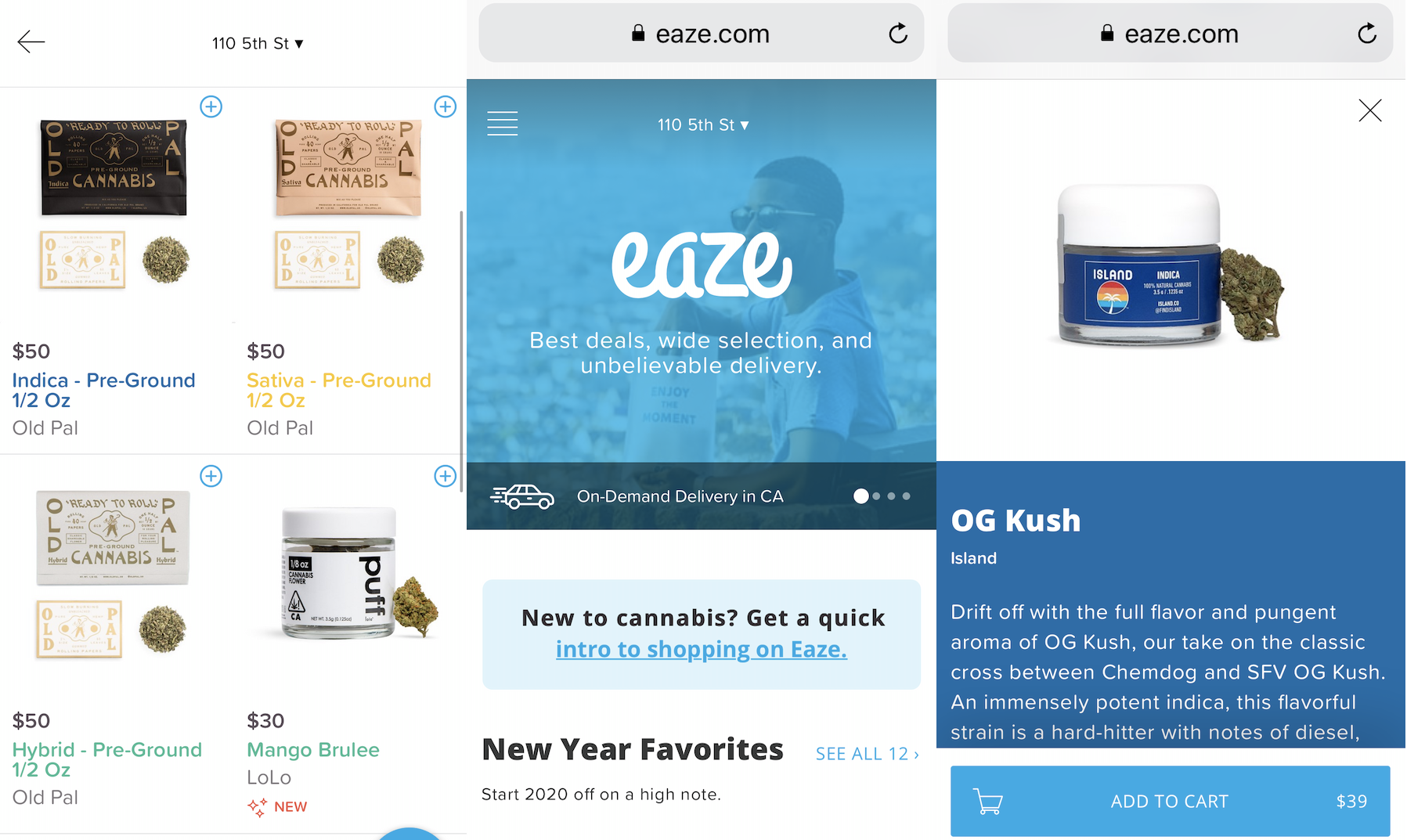

The news comes as Eaze is hoping to pull off a “verticalization” pivot, moving beyond online storefront and delivery of third-party products (rolled joints, flower, vaping products and edibles) and into sourcing, branding and dispensing the product directly. Instead of just moving other company’s marijuana brands between third-party dispensaries and customers, it wants to sell its own in-house brands through its own delivery depots to earn a higher margin. With a number of other cannabis companies struggling, the hope is that it will be able to acquire brands in areas like marijuana flower, pre-rolled joints, vaporizer cartridges, or edibles at low prices.

An Eaze spokesperson confirmed that the company plans to announce the pivot in the coming days, telling TechCrunch that it’s “a pretty significant change from provider of services to operating in that fashion but also operating a depot directly ourselves.”

The startup is already making moves in this direction, and is in the process of acquiring some of the assets of a bankrupt cannabis business out of Canada called Dionymed — which had initially been a partner of Eaze’s, then became a competitor, and then sued it over payment disputes, before finally selling part of its business. These assets are said to include Oakland dispensary Hometown Heart, which it acquired in an all-share transaction (“Eaze effectively bought the lawsuit,” is how one source described the sale). This will become Eaze’s first owned delivery depot.

In a recent presentation deck that Eaze has been using when pitching to investors — which has been obtained by TechCrunch — the company describes itself as the largest direct-to-consumer cannabis retailer in California. It has completed more than 5 million deliveries, served 600,000 customers and tallied up an average transaction value of $85.

To date, Eaze has only expanded to one other state beyond California, Oregon. Its aim is to add five more states this year, and another three in 2021. But the company appears to have expected more states to legalize recreational marijuana sooner, which would have provided geographic expansion. Eaze seems to have overextended itself too early in hopes of capturing market share as soon as it became available.

An employee at the company tells us that on a good day Eaze can bring in between $800,000 and $1 million in net revenue, which sounds great, except that this is total merchandise value, before any cuts to suppliers and others are made. Eaze makes only a fraction of that amount, one reason why it’s now looking to verticatlize into more of a primary role in the ecosystem. And that’s before considering all of the costs associated with running the business.

Eaze is suffering from a problem rampant in the marijuana industry: a lack of working capital. Since banks often won’t issue working capital loans to weed-related business, deliverers like Eaze can experience delays in paying back vendors. A source says late payments have pushed some brands to stop selling through Eaze.

Another drain on its finances have been its marketing efforts. A source said out-of-home ads (billboards and the like) allegedly were a significant expense at one point. It has to compete with other pot purchasing options like visiting retail stores in person, using dispensaries’ in-house delivery services, or buying via startups like Meadow that act as aggregated online points of sale for multiple dispensaries.

Indeed, Eaze claims that its pivot into verticalization will bring it $204 million in revenues on gross transactions of $300 million. It notes in the presentation that it makes $9.04 on an average sale of $85, which will go up to $18.31 if it successfully brings in ‘private label’ products and has more depot control.

Selling weed isn’t eazy

The poor margins are only one of the problems with Eaze’s current business model, which the company admits in its presentation have led to an inconsistent customer experience and poor customer affinity with its brand — especially in the face of competition from a number of other delivery businesses.

Playing on the on-demand, delivery-of-everything theme, it connected with two customer bases. First, existing cannabis consumers already using some form of delivery service for their supply; and a newer, more mainstream audience with disposable income that had become more interested in cannabis-related products but might feel less comfortable walking into a dispensary, or buying from a black market dealer.

It is not the only startup that has been chasing that audience. Other competitors in the wider market for cannabis discovery, distribution and sales include Weedmaps, Puffy, Blackbird, Chill (a brand from Dionymed that it founded after ending its earlier relationship with Eaze), and Meadow, with the wider industry estimated to be worth some $11.9 billion in 2018 and projected to grow to $63 billion by 2025.

Eaze was founded on the premise that the gradual decriminalisation of pot — first making it legal to buy for medicinal use, and gradually for recreational use — would spread across the US and make the consumption of cannabis-related products much more ubiquitous, presenting a big opportunity for Eaze and other startups like it.

It found a willing audience among consumers, but also tech workers in the Bay Area, a tight market for recruitment.

“I was excited for the opportunity to join the cannabis industry,” one source said. “It has for the most part has gotten a bad rap, and I saw Eaze’s mission as a noble thing, and the team seemed like good people.”

Eaze CEO Ro Choy

That impression was not to last. The company, this employee was told when joining, had plenty of funding with more on the way. The newer funding never materialised, and as Eaze sought to figure out the best way forward, the company cycled through different ideas and leadership: former Yammer executive Keith McCarty, who cofounded the company with Roie Edery (both are now founders at another Cannabis startup, Wayv), left, and the CEO role was given to another ex-Yammer executive, Jim Patterson, who was then replaced by Ro Choy, who is the current CEO.

“I personally lost trust in the ability to execute on some of the vision once I got there,” the ex-employee said. “I thought that on one hand a picture was painted that wasn’t the truth. As we got closer and as I’d been there longer and we had issues with funding, the story around why we were having issues kept changing.” Several sources familiar with its business performance and culture referred to Eaze as a “shitshow”.

No ‘Push For Kush’

The quick shifts in strategy were a recurring pattern that started well before the company got tight financial straits.

One employee recalled an acquisition Eaze made several years ago of a startup called Push for Pizza. Founded by five young friends in Brooklyn, Push for Pizza had gone viral over a simple concept: you set up your favourite pizza order in the app, and when you want it, you pushed a single button to order it. (Does that sound silly? Don’t forget, this was also the era of Yo, which was either a low point for innovation, or a high point for cynicism when it came to average consumer intelligence… maybe both.)

Eaze’s idea, the employee said, was to take the basics of Push for Pizza and turn it into a weed app, Push for Kush. In it, customers could craft their favourite mix and, at the touch of a button, order it, lowering the procurement barrier even more.

The company was very excited about the deal and the prospect of the new app. They planned a big campaign to spread the word, and held an internal event to excite staff about the new app and business line.

“They had even made a movie of some kind that they showed us, featuring a caricature of Jim” — the CEO at a the time — “hanging out of the sunroof of a limo.” (I’ve been able to find the opening segment of this video online, and the Twitter and Instagram accounts that had been created for Push for Kush, but no more than that.)

Then just one week later, the whole plan was scrapped, and the founders of Push for Pizza fired. “It was just brushed under the carpet,” the former employee said. “No one could get anything out of management about what had happened.”

Something had happened, though: the company had been taking payments by card when it made the acquisition, but the process was never stable and by then it had recently gone back to the cash-only model. Push for Kush by cash was less appealing. “They didn’t think it would work,” the person said, adding that this was the normal course of business at the startup. “Big initiatives would just die in favor of pushing out whatever new thing was on the product team’s radar.”

Eaze’s spokesperson confirmed that “we did acquire Push For Pizza . . but ultimately didn’t choose to pursue [launching Push For Kush].”

Payments were a recurring issue for the startup. Eaze started out taking payments only in cash — but as the business grew, that became increasingly problematic. The company found itself kicked off the credit card networks and was stuck with a less traceable, more open to error (and theft) cash-only model at a time when one employee estimated it was bringing in between $800,000 and $1 million per day in sales.

Eventually, it moved to cards, but not smoothly: Visa specifically did not want Eaze on its platform. Eaze found a workaround, employees say, but it was never above board, which became the subject of the lawsuit between Eaze and Dionymed. Currently the company appear to only take payments via debit cards, ACH transfer, and cash, not credit card.

Another incident sheds light on how the company viewed and handled security issues.

Can Eaze rise from the ashes?

At one point, employees allegedly discovered that Eaze was essentially storing all of its customer data — including users’ signatures and other personal information — in an Azure bucket that was not secured, meaning that if anyone was nosing around, it could be easily discovered and exploited.

The vulnerability was brought to the company’s attention. It was something that was up to product to fix, but the job was pushed down the list. It ultimately took seven months to patch this up. “I just kept seeing things with all these huge holes in them, just not ready for prime time,” one ex-employee said of the state of products. “No one was listening to engineers, and no one seemed to be looking for viable products.” Eaze’s spokesperson confirms a vulnerability was discovered but claims it was promptly resolved.

Today, the issue is a more pressing financial one: the company is running out of money. Employees have been told the company may not make its next payroll, and AWS will shut down its servers in two days if it doesn’t pay up.

Eaze’s spokesperson tried to remain optimistic while admitting the dire situation the company faces. “Eaze is going to continue doing everything we can to support customers and the overall legal cannabis industry. We’re excited about the future and acknowledge the challenges that the entire community is facing.”

As medicinal and recreational marijuana access became legal in some states in the latter 2010s, entrepreneurs and investors flocked to the market. They saw an opportunity to capitalize on the end of a major prohibition — a once in a lifetime event. But high government taxes, enduring black markets, intense competition, and a lack of financial infrastructure willing to deal with any legal haziness have caused major setbacks.

While the pot business might sound chill, operations like Eaze depend on coordinating high-stress logistics with thin margins and little room for error. Plenty of food delivery startups from Sprig to Munchery went under after running into similar struggles, and at least banks and payment processors would work with them. With the odds stacked against it, Eaze has a tough road ahead.