Scott Bade is special series editor of the TechCrunch Global Affairs Project and a regular contributor on foreign affairs. He's a former speechwriter for Mike Bloomberg and co-author of "More Human: Designing a World Where People Come First."

More posts by this contributor

The TechCrunch Global Affairs Project examines the increasingly intertwined relationship between the tech sector and global politics.

It should come as no surprise that government bureaucracies move slowly. After all, over a year into its term, the Biden administration has successfully filled fewer than half of its key positions a year. But that just makes this week’s launch of the State Department’s Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy (CDP), just six months after it was announced, seem positively nimble by comparison.

It will have to be if it is to succeed. “The United States is the most technologically advanced country on Earth,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in a speech announcing the bureau last year at the Foreign Service Institute. “The State Department should be empowered by that strength.”

Yet until now technology has been, if not an afterthought, certainly not front and center of American diplomacy. Despite the establishment of a cyber office in 2011 under Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the office was downgraded during the Trump administration.

No longer. “The last few years have made evident how vital cybersecurity and digital policy are to America’s national security,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken wrote State Department staff in an email on Monday provided to TechCrunch. “We’re in a contest over the rules, infrastructure and standards that will define our digital future.”

With that in mind, several clear policy goals of the new bureau have emerged. Some are quite expansive, like reducing national security risks from cyber activity and emerging technology and ensuring U.S. leadership in the global technology competition.

Other objectives, like setting technical standards in international fora and defending an open, intraoperative internet in spite of the actions of authoritarian countries like China and Russia, are more concrete and defined. I was encouraged to see Secretary Blinken tweet out his support last week for Doreen Bogdan-Martin’s candidacy to lead the International Telecommunications Union, one of the main intergovernmental organizations regulating the global internet.

But first, the State Department itself needs an update. Simply put, the State Department is operationally out of date, which is why the bureau’s first imperative, one official tells me, is to modernize the Foreign Service to allow diplomats to better connect with the digital global environment. That might mean experimenting with new tech like Zoom to be present in places diplomats can’t be physically, or more creative use of social media. Using the metric of how many embassies or consulates you have in a country as a sign of your presence is antiquated now, the official notes. “The establishment of the CDP bureau is a key piece of Secretary Blinken’s plans to build a State Department ready to meet the tests of the 21st century,” according to a State Department spokesperson.

Beyond that, the bureau is still in formation, but in conversations with current and former State department officials and outside experts, I’ve learned what officials hope to get out of the bureau.

CDP will have three policy buckets: international cyber security, digital policy and digital freedom. Each roughly corresponds to preexisting competencies: the cyber coordinator office (created back in 2011), the Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs and the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, respectively. It will be run by a yet-to-be-confirmed ambassador-at-large; in the meantime, career diplomat Jennifer Bachus will run the team as principal deputy assistant secretary.

While the new bureau will deal with the day-to-day, a separate special envoy position will also be created to focus on more long-term issues around emerging and critical technologies like AI, quantum and biotechnology.

Missing in action no more?

The “decision to stand up a new bureau is an indicator of how seriously [the Biden administration] see these threats of the need to have more thought leadership and diplomatic capacity,” Eileen Donahoe, a former U.S. ambassador who now runs the Stanford Global Digital Policy Incubator, tells me.

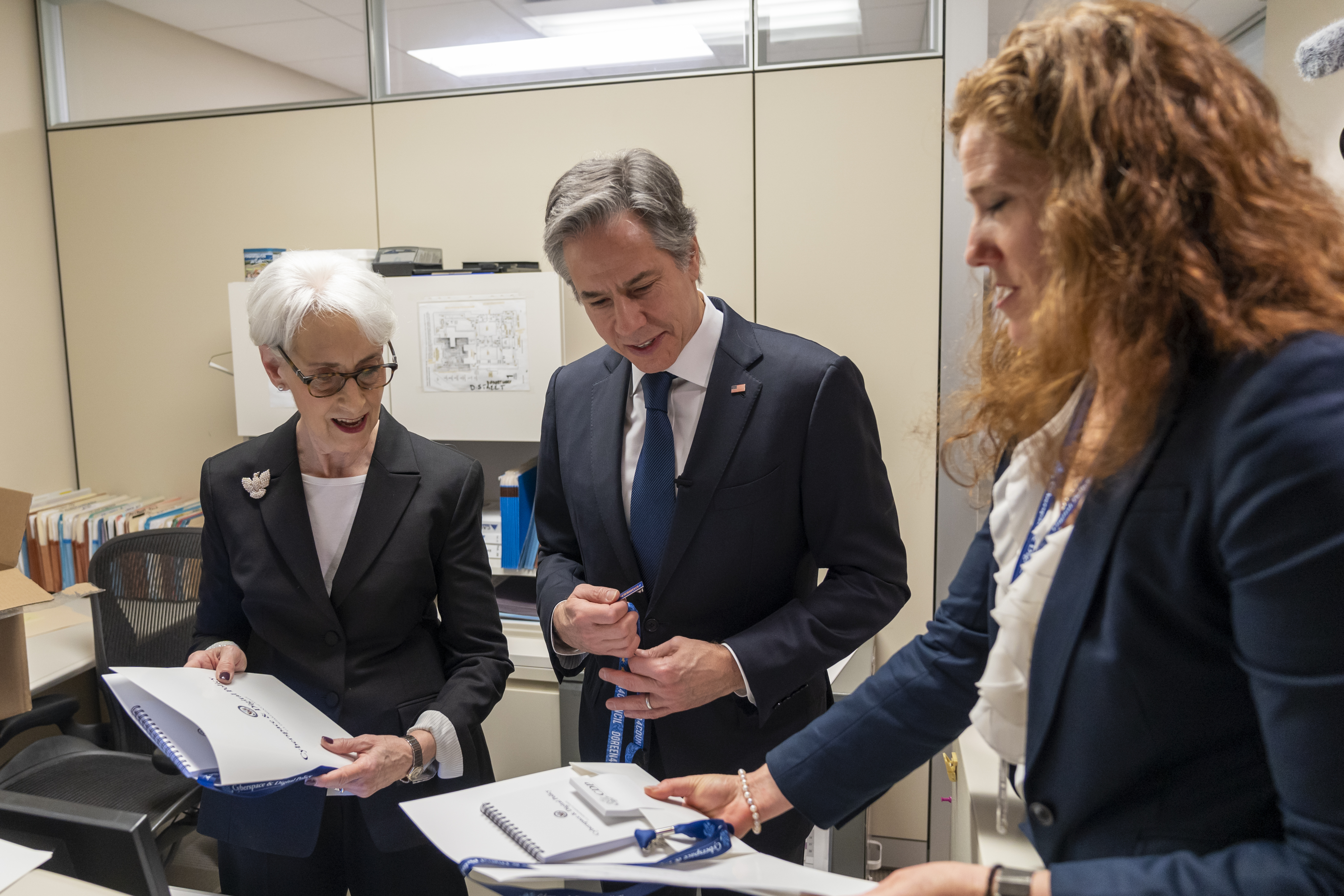

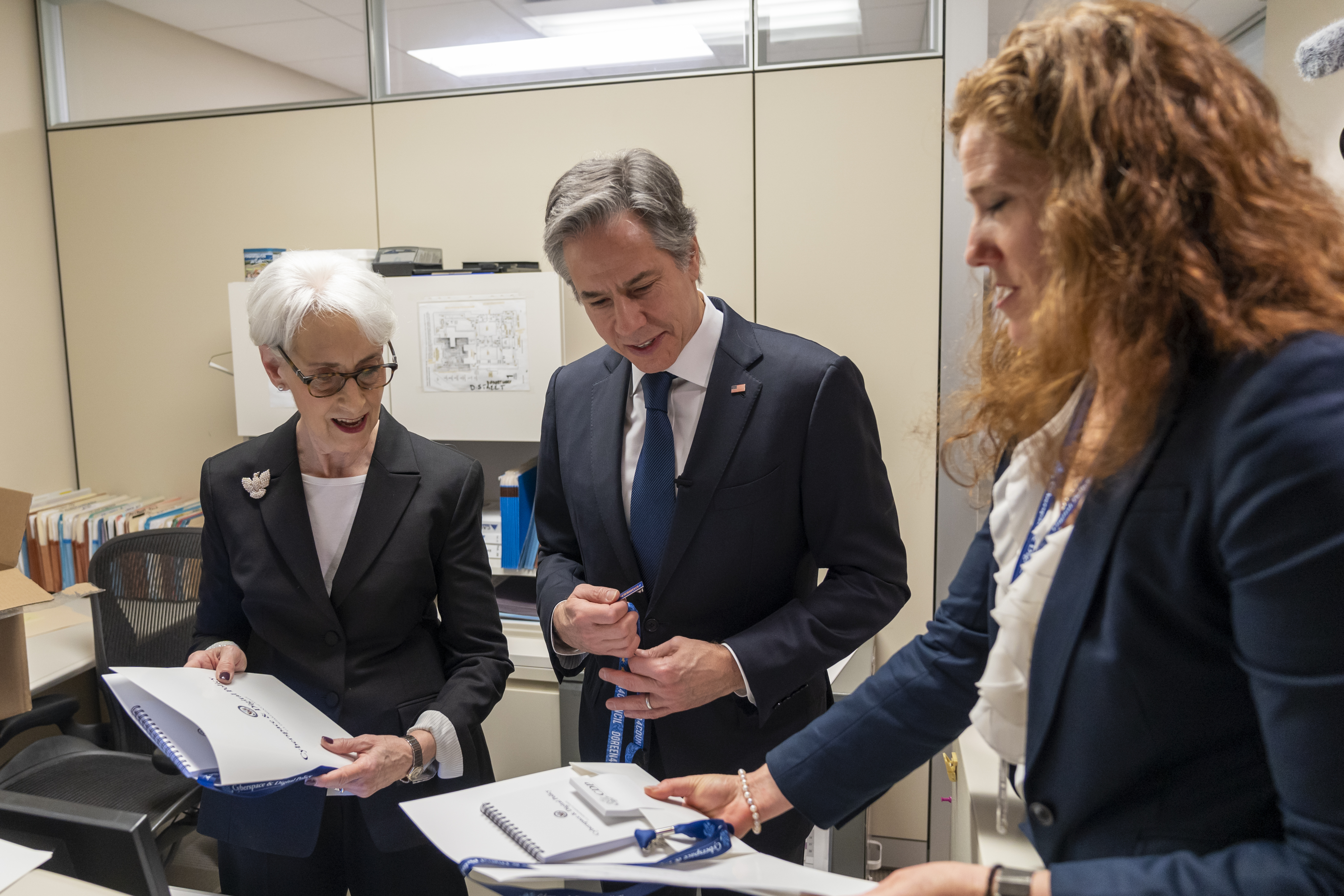

One sign of that seriousness is that both offices will, for at least a year, report directly to Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, the department’s number two official. This is a good thing, says Chris Painter, who was the Obama administration’s top diplomat on cyber issues. Sherman, he says, has a long history with cyber issues and worked to integrate technology issues at regional bureaus she ran earlier in her career.

Secretary Blinken and Deputy Secretary Sherman visit the new Cyberspace and Digital Policy Bureau. Image Credits: U.S. State Deparment/Ron Przysucha

CDP will need that high-level support. The State Department is playing catch up, I’m told, and attempting to bring its expertise — diplomacy and knowledge of international relations — to more technical policymakers at the Departments of Commerce, Energy, and other agencies. The implication is clear: State’s voice has been missing in the interagency process and opportunities have been missed both at home and abroad.

For example, as Nate Picarsic and Emily de la Bruyère have written, the U.S. has been largely absent from the politics of the intergovernmental organizations that are quietly setting the global standards of technology. As a result the U.S. has ceded ground to others, especially Russia and China, but even the European Union, with massive implications for who controls the future of technology.

And as new international entities emerge, like the EU-U.S. Trade and Technology Council or the Quad’s technology working group, the State Department needs to be able to coordinate and advise. Under the Trump administration, you “had good, talented people,” working these issues, Painter tells me, “but no one at the leadership level [able] both to deal with the White House and senior counterparts and foreign counterparts. [The new bureau] helps fill that gap.”

“This is a real down payment by the department,” says Yll Bajraktari, a former national security official who is now the CEO of Special Competitive Studies Project, an AI advocacy group. “Integrating the department’s capacity for cybersecurity, digital infrastructure and governance issues including internet freedom will help create a coherent diplomatic strategy.”

Still loading…

I’m struck by several obstacles the new bureau will face, however. Some are institutional.

For example, there are a myriad of challenges out there, says Painter, from writing new cyber norms to countering state action to promoting human rights issues. “These issues are being debated in almost every fora. That means we have to be there, actively planning, and that takes people and attention.” Simply staffing the bureau with enough qualified people to handle all these issues will be a lift.

Some policy advocates I spoke with fear that the new bureau may end up focused on cyber issues to the detriment of issues like democracy and human rights. If personnel is policy, the proof will be in how the State Department prioritizes staffing the new bureau — and who the ambassador-at-large will be (when asked, a State Department official told me that there will be new staff positions covering all policy areas).

The new bureau also has to “mainstream these issues across the department,” Painter adds, but that will take time. Secretary Blinken wants the department to think and act differently but how willing will a recently demoralized foreign service be to embrace the change that is necessary to make policy on highly technical subjects many may not be familiar with? Diplomats will have to learn how to assert themselves on technological issues in the interagency process with departments like Defense and Homeland Security with far greater experience on these issues. “We have to be patient as State now builds expertise,” Bajraktari says.

Other challenges are more strategic. I’ve not been shy about calling for the use of technology in U.S. foreign policy and was thrilled when the U.S. slammed Russia with export controls in response to its invasion of Ukraine. If CDP is to succeed, it has to be allowed to influence policy outside the narrow remit of cyber treaties and technical policy (as important as they are).

“You can’t put cyber in a box,” Painter tells me. “It has to be part of all the tools we have.” After all, he notes, we don’t have a cyber problem with Russia and China but a Russia problem and a China problem full stop.

Still other challenges combine the institutional and policy. “What’s really needed is understanding the interconnectivity between all of these issues,” says Donahoe, who advised those that created the new bureau. She points to the fact that freedom of speech, what we once thought of as a human rights issue, has become a weapon when used as disinformation. State will also have to manage conflicting priorities across agencies — for example, will it side with Commerce officials who want to back American tech companies or antitrust officials who want to work with the EU to neuter them?

Meanwhile, so many aspects of tech, from cybercrime to cybersecurity norms, have yet to be fleshed out internationally. Can Washington forge agreement among its allies over what a democratic internet looks like? Does the U.S. have the diplomatic and bureaucratic skill to set norms in the face of China and Russia’s efforts to set the agenda themselves? Experts wondered if Russia would launch a cyber war on the West in response to its support for Ukraine, but we still have no idea what that even means.

As authoritarians increasingly use technology to build up dictatorships and undermine democracy, it is good that American diplomats are thinking seriously about how technology fits into American diplomacy and its efforts to bolster democracy around the world. These are difficult issues that require an all-of-government approach. Let’s hope the State Department learns quickly.