The “Pineapple Express” that dropped several inches of rain over the Bay Area last week left the ground saturated. The next storm front expected to arrive tomorrow is expected to bring disruption and destruction on a massive scale.

It’s a decent metaphor for our startup ecosystem: Just as there aren’t enough sandbags in San Francisco to keep everyone’s house dry, rising interest rates, skittish investors and looming economic uncertainty are poised to bring valuations down even further in 2023.

“In a culture where growing valuations are worn like a badge of honor, founders may fear that taking a down round would render them Silicon Valley pariahs,” writes Holden Spaht, managing partner at private equity firm Thoma Bravo.

Full TechCrunch+ articles are only available to members.

Use discount code TCPLUSROUNDUP to save 20% off a one- or two-year subscription.

In a TC+ column, Spaht encourages entrepreneurs to revisit the operational and fundraising tactics they leaned on in the bygone era of cheap money.

“The funding route you take has enormous consequences for the future of your company, and so it shouldn’t be clouded by ego or driven by media appetites,” he says.

Cutting back is always an option, but not every company is in a position to bootstrap or freeze hiring, which is why Spaht suggests exploring “trade-offs” like convertible notes.

Everyone gets wet when it rains, but accepting a down round allows founders to keep building, “and you have the benefit of resetting expectations of value in a challenging market,” writes Spaht.

Happy new year!

Walter Thompson

Editorial Manager, TechCrunch+

@yourprotagonist

How to make the most of your startup’s big fundraising moment

Image Credits: Anatolij Fominyh / EyeEm (opens in a new window) / Getty Images

No matter the size, investments are a sign of validation for any startup.

However, “when you see other companies raising hundreds of millions of dollars, it can be easy to think no one will be interested in hearing about your startup’s much smaller round,” writes Hum Capital CMO Scott Brown.

In his marketing playbook for early-stage startups, Brown explains how founders can use fundraising announcements to maximize media interest, comply with SEC guidelines and align more closely with investors to “get the most bang for their buck.”

How to protect your IP during fundraising so you don’t get ripped off

Image Credits: MirageC (opens in a new window) / Getty Images

Most investors won’t sign a non-disclosure agreement before reviewing your pitch because your idea is probably not worth stealing.

That’s not an insult, just a statement of fact.

The odds are low that you’re the first person to come up with an idea, and an NDA could create legal hassles for VCs who interact with hundreds of entrepreneurs each year, many of whom are trying to solve the same set of problems.

“Not all concepts developed by startups are legally protectable,” writes Alison Miller, trial lawyer at Holwell Shuster & Goldberg LLP. “The next best thing founders can do is to signal as much as possible that pitch materials shared with funders are confidential.”

Six climate tech trends to watch for in 2023

Image Credits: Getty Images

Tim De Chant looked back on his reporting from last year to sketch out his predictions for where he believes climate tech is heading:

- Software to deploy and manage renewable power

- Direct air capture

- Green hydrogen

- Home renovation contractor software

- Critical minerals mining

- Fusion power

“Will 2023 be the inflection point that marks the start of exponential growth? I suspect we’ll know more around this time next year.”

Redefining ‘founder-friendly’ capital in the post-FTX era

Image Credits: stockcam (opens in a new window) / Getty Images

Could the FTX debacle have been avoided if investors had taken a more active interest in the company’s operations?

Given the chilly climate for late-stage fundraising and widespread economic uncertainty, “it’s time for the startup community to redefine what “founder-friendly” capital means and balance both the source and cost of that capital,” writes Blair Silverberg, co-founder and CEO of Hum Capital.

In a TC+ guest post, he weighs the relative benefits of active versus passive investors, breaks down the basics of debt financing, and shares advice “for founders seeking a better balance of capital and external expertise for their businesses.”

High-growth startups should start de-risking their path to IPO now

Image Credits: Richard Drury (opens in a new window) / Getty Images

It sounds counterintuitive, but in this chilly fundraising environment, late-stage startups need to plan to go public when the market opens up.

“While some companies delay their IPOs, others can play catch-up and prepare for the time when the open market itches to invest again,” writes Carl Niedbala, COO and co-founder of commercial insurance broker Founder Shield.

In a detailed TC+ article, he looks at why “sensible companies are de-risking their public path,” which sectors are best positioned, and perhaps most notably, which benchmarks startups can use to tell if “an IPO is in their future.”

What to look for in a term sheet as a first-time founder

Image Credits: syolacan (opens in a new window) / Getty Images

Most financing contacts between early-stage startups and investors take the form of a SAFE note, also known as a simple agreement for future equity.

Legally binding, the document establishes both a company’s valuation and deal terms. “Once you get the term sheet, the game has really begun,” says James Norman, managing partner at Black Operator Ventures.

To help first-time founders better understand “what to ask for” and which red flags to avoid, Connie Loizos interviewed Norman, along with Mandela Schumacher-Hodge Dixon, CEO of AllRaise, and Kevin Liu of Techstars and Uncharted Ventures.

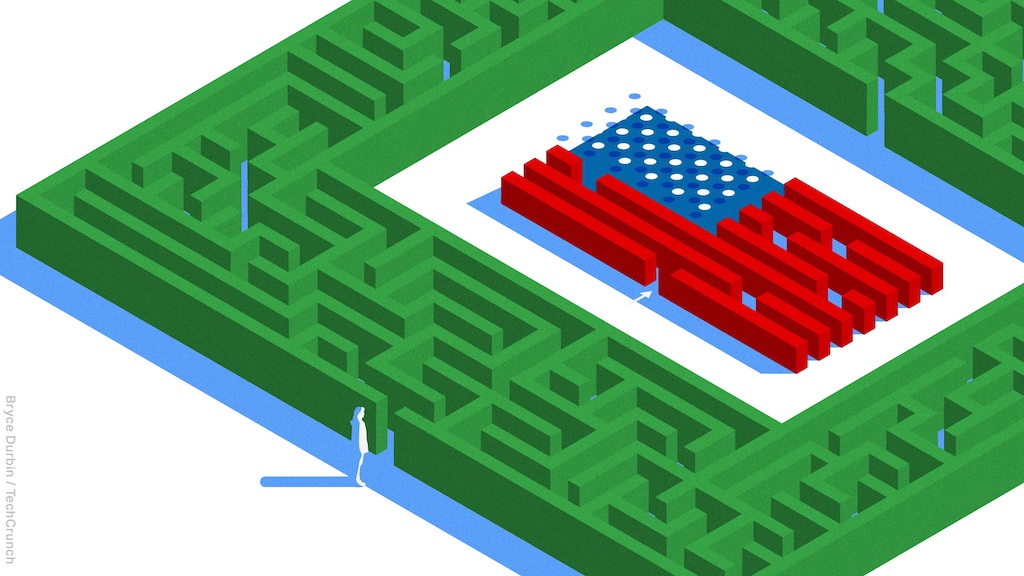

Dear Sophie: Do employees have to stop working until they get their EAD?

Image Credits: Bryce Durbin/TechCrunch

Dear Sophie,

One of our employees is on an H-4 visa and has an Employment Authorization Document. It’s been five months since he filed to renew his EAD, which will expire next month. Is there any way to expedite this process? Does he have to stop working if he doesn’t receive his new EAD card before his old one expires?

Because it’s taking so long to get EAD cards, we’re worried about another of our employees, who has an L-2 visa with an EAD scheduled to expire early next year.

In addition, the H-4 visa employee wants to visit his family in India because it’s been more than three years since he last went. Will he and his family be able to return to the U.S. after four weeks?

— Mindful Manager

TechCrunch+ roundup: Normalizing down rounds, 2023 climate trends, term sheet basics by Walter Thompson originally published on TechCrunch

climate tech trends to watch for in 2023

climate tech trends to watch for in 2023