Tesla has been masking its lobbying efforts on solar panels and battery storage through the Energy Freedom Coalition of America, a trade association that is little more than a front for the automaker and alternative energy company, public documents suggest.

SolarCity, which Tesla bought in 2016, began the practice of using the EFCA to promote its products and services without acknowledging it was the only significant member of the organization. EFCA was initially portrayed as a solar advocacy group with grassroots support.

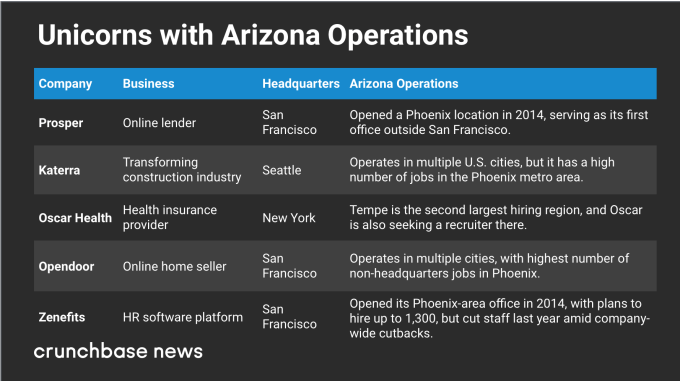

When rule changes threatened payments to Arizonans with domestic solar panels in 2016, EFCA knew just what to do. It launched the Arizona Solar Pledge for citizens “to demonstrate their support for energy choice and add their names to the growing coalition determined to protect Arizona rooftop solar customers.”

Anyone signing the petition would “demonstrate to … the broader political community that the people of Arizona stand with rooftop solar and energy choice,” wrote an EFCA spokesperson at the time.

EFCA noted that its list of members included Silevo, SolarCity Corporation, ZEP Solar, Go Solar, 1 Sun Solar Electric, and Ecological Energy Systems.

However, far from being a grassroots environmental advocacy organization or a broad trade body, the EFCA seems to represent little more than the lobbying arm of Tesla’s energy division.

Three of its named “member” businesses — Silevo, SolarCity and Zep Solar – are actually subsidiaries of Tesla. Two of the remaining companies are small regional solar installers. TechCrunch could not immediately identify Go Solar LLC.

Tesla would not answer questions about EFCA’s membership, funding or control. However, a spokesperson wrote, “Since the [SolarCity] acquisition, Tesla has been winding down its involvement with the coalition, and to the extent we have worked with them, it’s largely been limited to legacy dockets that have already been in progress for multiple years.”

The EFCA is a non-profit corporation formed in Delaware that describes itself blandly as a “national advocacy organization that seeks to promote public awareness of the benefits of solar and alternative energy.”

It was slightly more forthcoming in a filing with the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission early in 2017, discussing proposed community solar gardens. EFCA wrote that it “represents a broad range of businesses that are fully integrated providers of distributed energy resources (DERs) products and services.” These, it wrote, could include rooftop solar, distributed generation, thermal and battery energy storage, and smart energy services, for residential, commercial, industrial and government customers.

Although EFCA’s legal representative for filings in New Hampshire has an EFCA email address, her LinkedIn profile shows that her job title is Campaign Projects Coordinator at Tesla. Recent filings on behalf of EFCA have been made by a senior policy advisor at Tesla. In fact, EFCA itself is listed as a Tesla subsidiary in filings with the SEC.

EFCA’s roots

Tesla lobbies under its own name in many parts of the country, so how did it come to be working under the guise of the EFCA, and why is it continuing to do so?

The story goes back to 2006, and the formation of SolarCity by two of Musk’s cousins, Lyndon Rive and Peter Rive. SolarCity took the novel approach of installing photovoltaic systems for no money down, instead leasing them to homeowners in exchange for decades of payments for cheaper, greener electricity. Musk invested in SolarCity and took the role of chairman.

SolarCity grew quickly, becoming the largest solar installer in the United States by 2013, despite a business model that required taking on mountains of debt. The company regularly sparred with traditional utility companies, often as part of a rooftop solar trade association called the Alliance for Solar Choice, or TASC.

In late 2015, rooftop solar was facing a tough situation in Nevada. NV Energy, the state’s monopoly electricity provider, wanted to slash domestic solar incentives, and the solar industry was fighting for its life. While SolarCity took a collaborative approach, its main rival, SunRun, suggested suspicious ties between the utility and Nevada’s governor.

SolarCity ultimately withdrew from TASC, saying that its focus was moving beyond residential solar. The new EFCA would “capture more of our interests,” a spokesperson told Utility Dive at the time. SolarCity persuaded a small Las Vegas company called 1 Sun Solar Electric, among others, to join EFCA. 1 Sun, which installs five to 10 residential solar systems in the city each month, was keen to protect its local business.

“There’s no way that a small company like ours would be able to go toe-to-toe with NV Energy,” Louise Helton, the company’s vice-president, told TechCrunch. “EFCA gave us standing with the public utility commission, and their attorneys are just stellar.”

Despite the resources EFCA could bring to bear, Nevada did reduce solar incentives at the end of 2015. Many national solar companies, including SolarCity and SunRun, subsequently left the state.

Towards the end of 2016, Tesla bought SolarCity for $2.6 billion, and EFCA along with it. State records and filings indicate that EFCA has now been active in over 30 proceedings in 16 states, and has retained lobbyists in at least Arizona, Utah, Montana, Florida, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Washington. It does not appear to have initiated any filings that would not benefit Tesla or its subsidiaries.

EFCA had no fewer than 23 lobbyists working for it in Arizona in 2016, while the organization spent $110,000 on lobbyists in Florida the next year, both according to Follow the Money. It has also hired multiple law firms to help it draft and submit filings across the nation.

None of the money for these activities came from 1 Sun, Helton told TechCrunch, nor has EFCA asked 1 Sun to work on the coalition’s behalf. “I would be available to do whatever, but they have not needed anything else from us,” Helton said. “It’s good to be part of something that is fighting the good fight, and giving that entity a flavor of not just being one giant organization, even though Tesla is definitely doing the heavy lifting. We’re very happy to help make it a little bit more diverse.”

EFCA’s recent activity

EFCA’s website is no longer active, and the coalition has not tweeted since early 2017. However, one exception to the organization’s low profile is in Hawaii, where EFCA initiated new filings in 2018 because, Tesla says, the coalition is a known entity there. Even those recent filings, however, are vague about who is actually lobbying in the state.

An EFCA filing in August 2018 stated, “EFCA Members provide solar and storage facilities and services in the State of Hawaii and/or are interested in expanding their provision of those services in the State.”

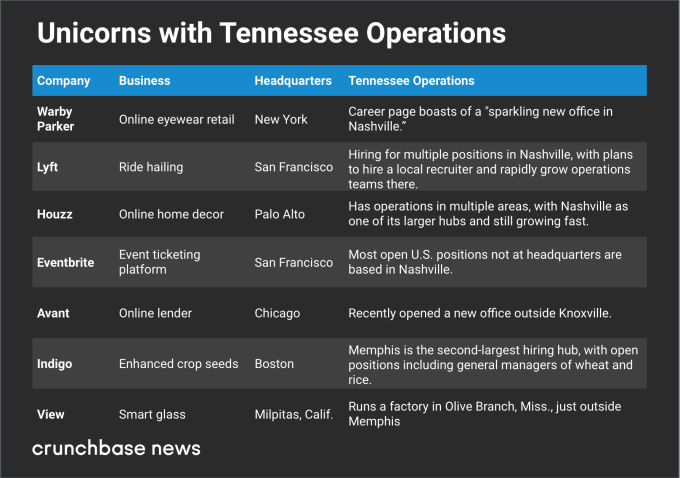

The only identifiable non-Tesla companies, 1 Sun Solar Electric and Ecological Energy Systems, are based in Nevada and Tennessee, and show no signs of expanding to the Pacific. Tesla, by contrast, has a massive solar plus storage facility on the island of Kauai.

Some of EFCA’s newer filings do reference Tesla, generally to note that the company owns SolarCity.

Tim LaPira, Associate Professor of Political Science at James Madison University, notes that it is virtually unknown for a trade association to be owned and controlled by a single company.

“It’s probably not illegal, but from a transparency perspective, it’s far, far from being ethical,” LaPira said. “When corporations lobby directly, there’s an understanding that they’re asking the government to do something to increase their profits. It’s a very different story when a credible trade association asks the government to do something because they’re not going to benefit directly — they’re asking for some common good. Tesla is trying to get the best of both worlds.”

EFCA continues to lobby state utility commissions, for example proposing changes to net metering and energy storage rules in California last month. That document did not mention Tesla at all.