If you are among those who thought that the scooter market sounded a little overhyped and overcrowded, we’ve gotten wind of a deal that could point to some impending consolidation. The on-demand scooter business Bird has agreed to acquire Scoot, a smaller two-wheeled mobility startup, sources tell TechCrunch.

The stage of the negotiations is not clear although from what our sources tell us, it sounds like the deal is not closed. Contacted for a response, both Scoot and Bird said they declined to comment on speculation.

If accurate, it would be far from a merger of equals. Scoot was last valued at around $71 million, having raised about $47 million in equity funding to date from Scout Ventures, Vision Ridge Partners, angel investor Joanne Wilson and more.

Bird is significantly larger. Led by chief executive officer Travis VanderZanden, earlier this year the company was working on a round of financing reportedly worth $300 million at a $2.3 billion valuation. We’ve been able to confirm that this round has now closed, although we don’t yet know the final amount or who the investors are. (Backers of Bird include Sequoia, Index, Charles River Ventures, Tusk Ventures, Upfront Ventures and dozens more.) Scoot would be Bird’s first full acquisition.

Scooting toward consolidation

It’s still very early days in the scooter market in terms of consumer adoption, but that hasn’t stopped people from launching a lot of startups and raising funding to capitalise on what many believe will be a big opportunity longer term.

That promise is made bigger by the regulatory structure of the scooter market. Similar to their approach to bikes, many cities restrict the number of licenses they give out to companies to run on-street, hourly scooter services. Winning a license can give a company a near-monopoly on building a business in that city.

It also means that a combination between two companies whose geographic footprints do not overlap becomes a much cheaper and faster way of instantly creating a bigger business.

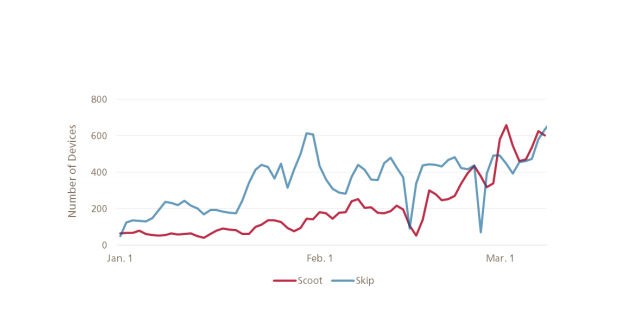

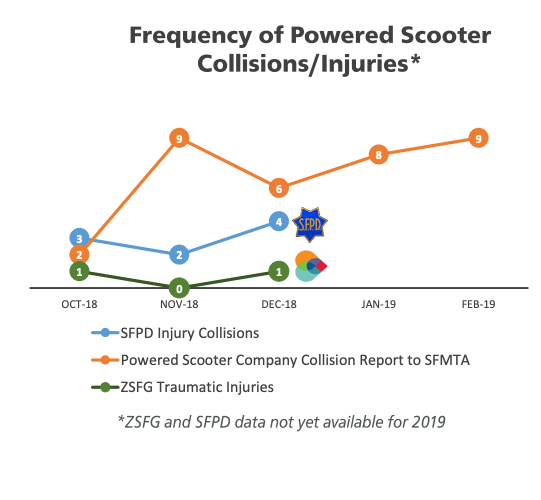

Notably, Scoot has a license to operate a pick-up/drop-off street service in the key market of San Francisco — where it competes with Skip, the only other licensed operator in the city. (Note: Bird last month did start up business again in SF, but only for the less popular offer of monthly rentals.)

What’s more, the two startups do not have any overlap in the rest of their footprints. Scoot is active in Barcelona, Spain and Santiago, Chile. Bird, on the other hand, has launched in about 100 cities spanning the U.S. and Europe, but its list does not include any of the cities where Scoot has rolled out its service.

Bird announced its new, two-seated electric vehicle earlier this week

On the vehicle front, the story is a little different. The two are providing, more or less, the same kinds of vehicles. Scoot has built out a network focused primarily on electric push scooters, seated scooters and electric bikes. Bird, meanwhile, has mostly built its service around electric push scooters, but just yesterday the company debuted its first seated vehicle to expand into a new product class.

Bird acquiring Scoot will help the two achieve better economies of scale in terms of vehicle purchasing power and device R&D.

It also helps them compete against the big boys. The market for scooters and other two-wheeled vehicles (collectively termed “micro-mobility”) is still a relatively new one, but Lyft and Uber have also waded in early to establish market share, as part of their own strategies to position themselves as the go-to platforms for any and all transportation needs.

Bird buying Scoot is one likely M&A move, but it’s not the only one.

Sources have told TechCrunch that an Uber acquisition of Skip (the other provider in SF) could also be in the works. Skip, much like Scoot, is another small player in the e-scooter market. To date, it has secured $31 million in venture capital funding from Initialized Capital, Accel and others.

Uber is already an active acquirer in the area of mico-mobility. If you remember, it acquired JUMP Bikes for $200 million in April 2018.

Uber’s acquisition of JUMP wasn’t surprising. In January 2018, the ride-hailing giant partnered with JUMP to launch Uber Bike, which lets Uber riders book JUMP bikes via the Uber app.

Other acquisitions in the nascent micro-mobility space include Lyft’s purchase of Motivate, a deal announced roughly one year ago. Motivate, the oldest and largest electric bike-share company in North America, did not disclose terms of the deal, though reports indicated it was asking for at least $250 million.

Bird — founded in 2017 — has yet to announce any acquisitions, although a spokesperson for the company said there have been quiet acqui-hires before now.

It was itself the subject of acquisition rumors for several months in 2018, too. Prior to Uber filing to go public in what was one of the most highly anticipated initial public offerings of the decade, many expected it to shell out cash for either Bird or Lime. From what we know, Uber was in discussions to acquire Bird, but ultimately it wasn’t able to meet Bird’s steep asking price.