Sinch, the Swedish company that competes with Twilio and others in the world of messaging and other communication APIs is making another big M&A play to build out its platform. It has acquired Pathwire, the cloud-based email provider behind Mailgun, Mailjet and Email on Acid. Sinch said it would pay $925 million in cash, with an additional 51 million new shares in Sinch. Based on yesterday’s closing price for Sinch (it’s traded on the Swedish stock exchange Nasdaq Stockhom and has a market cap of $13.7 billion), this works out to an enterprise value of $1.9 billion (SEK 16.6 billion).

The deal is very large in its own right, but also continues to set up Sinch as a (maybe “the”) key competitor to Twilio. The U.S.-based communications API giant acquired Sendgrid — another major email API provider that, like Pathwire’s products, is popular with developers — for $2 billion in 2018. That was an all-stock deal.

It also points to just how significant email is as a key part of the communications landscape, with services you may never even think twice about but use all the time — booking confirmations, receipts and password resets — falling under this umbrella. Quoting figures from Technavio, Sinch estimates the worldwide delivery market for email is worth $16 billion annually. This figure includes payments for email services, related investments and so on; and specifically “transactional email” (the area Pathwire covers) accounts for 60%+ of this amount.

It also underscores the massive consolidation at work at the moment in this sector. Even Pathwire itself is an example of that. Prior to this exit, it was owned by Thoma Bravo and was itself an acquirer of substantial businesses operating in the same general category of email-as-a-service, with its latest acquisition, of Email on Acid, announced as recently as June of this year. (Was that the spur that got Sinch to bite and buy Pathwire, I wonder?)

This is Sinch’s biggest acquisition to date, and it’s also a huge business. Collectively, Pathwire has shaped up to be a massive platform for those building email experiences within apps, marketing campaigns and other communications services. Today it counts more than 100,000 businesses as customers, which works out to millions of people using Mailjet, Mailgun and other Pathwire products (as well as the analytics and everything else that comes with this). That customer list includes Lyft, Kajabi, Microsoft, Iterable, and DHL.

“Every form of digital communications has its unique benefits, and delivering high quality at scale requires both extensive technical capabilities and deep subject matter expertise“, comments Oscar Werner, Sinch CEO, in a statement. “Together with Pathwire, we will be able to offer a best-of-breed product set, across messaging, voice and email, that empowers businesses and developers to craft an unmatched, digital, customer experience.”

This also gives Sinch a much bigger foothold in the U.S. market, where it has made other acquisitions, such as buying Inteliquent for $1.14 billion earlier this year. (Pathwire is based in San Antonio, TX.)

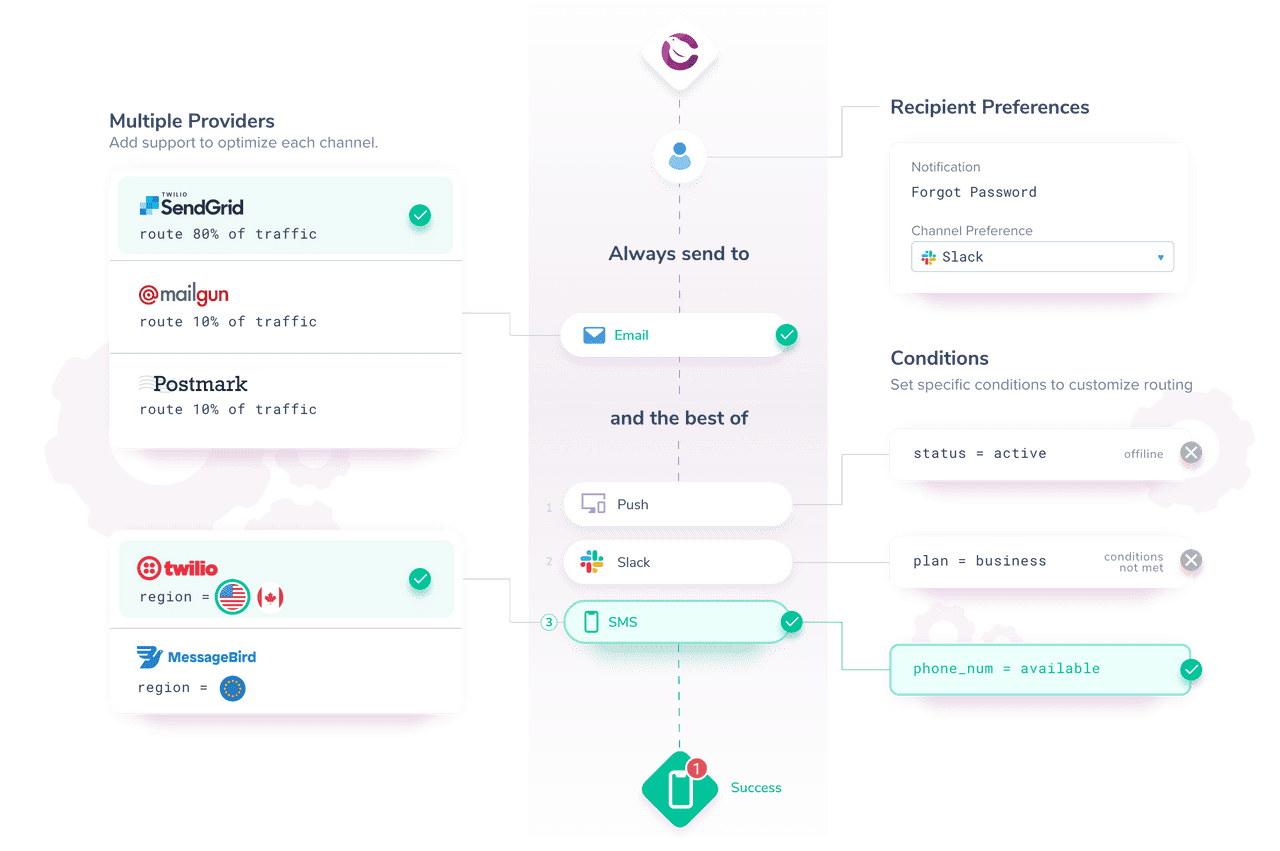

As with other services in the wider platform that Sinch has built out, the bigger concept that it is pursuing with the Pathwire acquisition is “embedded communications.”

Messaging, voice services, email and other communications tools are hard to build from the ground up, and for many of the companies that rely on them in their apps, websites, and other customer interactions, it’s not the essential core of their services, so putting resources into building them would be costly, distracting, and hard to keep updated and maintained in the longer term. APIs have changed the game here by letting developers or others integrate communications services built and powered by others, into these various experiences. The same API concept has been applied in other furiously complex areas of tech such as financial services and payments.

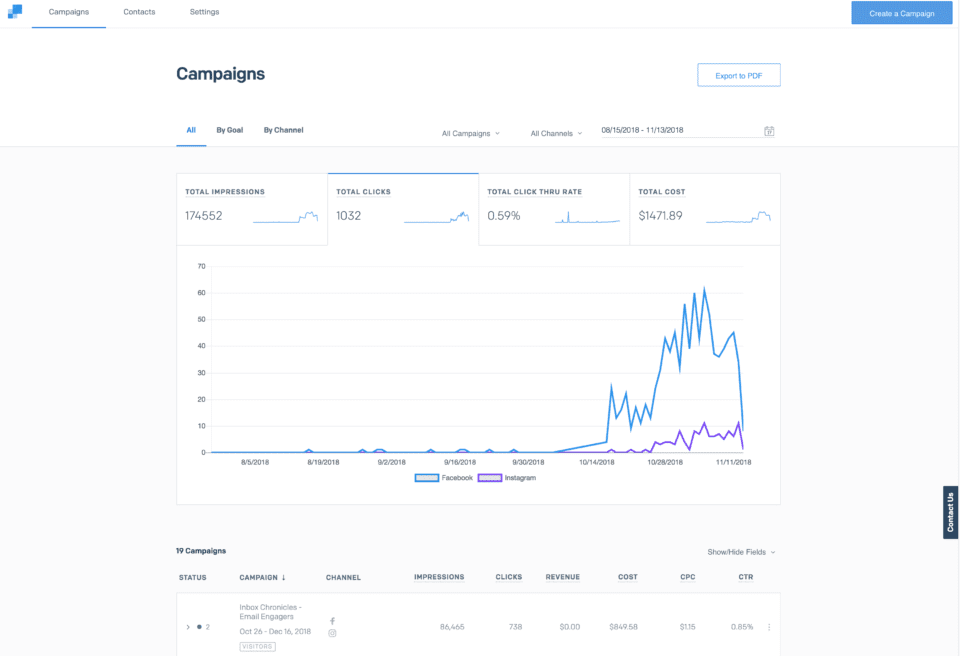

Pathwire’s products cover a few different bases, however, which is what makes it a compelling buy for Sinch. Mailgun is its big developer-focused API play in cloud-based communications. Mailjet, meanwhile is a little more accessibility for less technical people, giving them the option to use drag-and-drop functionality to integrate the email APIs. Email on Acid is another step in that low-code direction, giving its users further features to ensure consistency of appearance across different delivery platforms and so on.

“Sinch and Pathwire are a natural fit: both companies have built their businesses around product excellence, a commitment to positive results for our customers, and a focus on clear, measurable outcomes. I’m proud of what the Pathwire team has accomplished, and I’m tremendously excited about this next step on our journey and the many opportunities we can unlock together”, comments Will Conway, Pathwire CEO, in a statement.

“We are proud of what we accomplished with Will and the Pathwire team over the past few years, investing in product initiatives, leadership, and M&A, including the acquisitions of Mailjet and Email on Acid,” added Hudson Smith, a Partner at Thoma Bravo. “Sinch is the perfect strategic partner to support Pathwire and continue to build on its market-leading position as the email communications partner of choice for developers and marketers.”

Pathwire, notably, was already profitable. Projected revenues for this year (ending December) are $132 million, with gross profit of $104 million, and adjusted EBITDA of $55 million in the same period.