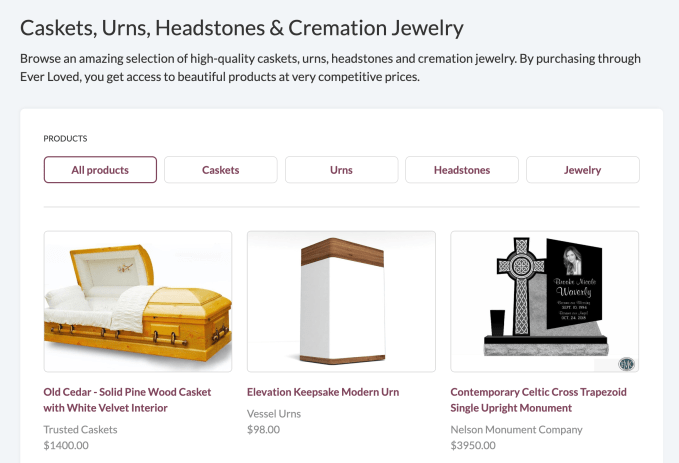

Fifty percent of families are scared they can’t cover the cost of a funeral. They end up overpaying because no one wants to comparison shop amidst a tragedy. That’s why ex-Googler Alison Johnston’s startup Ever Loved built a free funeral crowdfunding tool. Now it’s addressing one of the most expensive parts of saying goodbye: burial. Today Ever Loved launches its online marketplace for caskets, urns, headstones and memorial jewelry.

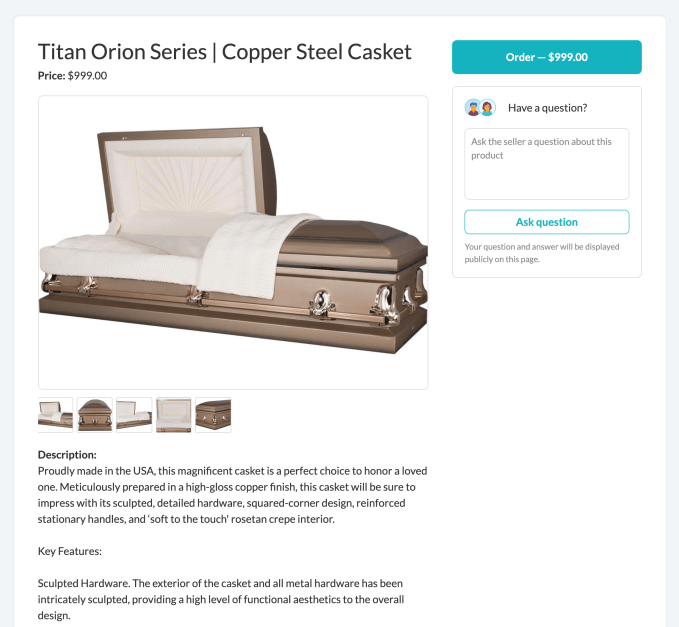

By sidestepping the overhead of a physical funeral home, Ever Loved can offer better prices while still earning a 10% margin. Its caskets cost 50% less than the average sold at a mortuary, according to the National Funeral Directors Association.

When I called a local San Francisco funeral home, the high markups came into focus. They quoted me $2,795 for a casket sold for $1,200 on Ever Loved.

“Most people don’t think to — or don’t want to — plan funerals in advance, which means that when someone passes away, the family is often scrambling,” Johnston tells me. “When this rush to make decisions is paired with extreme grief, many people don’t do anywhere close to the same amount of research as they would with another several-thousand-dollar purchase. When combined with the fact that most funeral homes don’t publish their prices online, it’s easy for families to spend much more than they need to.”

Johnston co-founded Ever Loved in late 2017 after a family member was diagnosed with terminal cancer. She discovered how few resources there were available for helping people plan and pay for funerals. She’d previously worked at Q&A app Aardvark through its acquisition by Google, then started online tutoring startup InstaEDU that eventually sold to Chegg. The consumer website building and e-commerce tools she’d grown used to weren’t available in the funeral industry, so she set out to build them. Ever Loved has raised seed funding from Social Capital and gone through Y Combinator.

Ever Loved co-founder and CEO Alison Johnston

“Tech too often merely makes life and work easier for those who already have it good,” she told me last year. “Tech that tempers tragedy is a welcome evolution for Silicon Valley.”

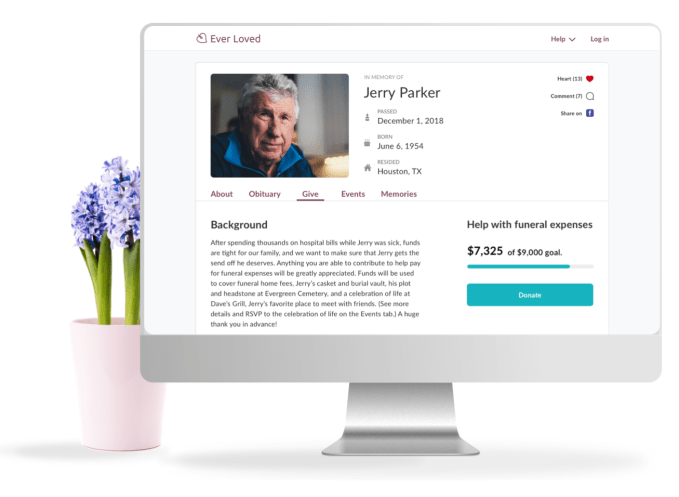

Ever Loved’s first focus was its funeral crowdfunding tool that let families ask the decedent’s loved ones to help contribute to offset the costs. Donors could leave a tip for Ever Loved, but otherwise it charged nothing beyond credit card processing fees. The tool was paired with a memorial website builder that families could use for distributing invites and collecting memories. Now Ever Loved is helping people plan thousands of funerals per month with revenue up nearly 20X year-over-year.

Now that it’s helping families raise money for remembrance services, Ever Loved wants to make sure they don’t get ripped off. The fact that there’s such low pricing transparency at funeral homes should clue you in that they try to pass off steep markups since customers might not have the energy to keep looking. “The average funeral home only helps with a funeral once every three days, meaning that many funeral homes need to charge high prices in order to cover their own fixed costs,” Johnston explains.

Remove the overhead costs and assist customers across geographies and there’s room for a strong business with more affordable prices. For example, a Stanford Blue Casket costs $990 on Ever Loved while one LA funeral home charges $1,600. The Last Supper Pieta Casket is $1,500 on Ever Loved but $6,580 from the funeral home. That funeral home had both of these listed under different names, further hindering the ability of customers to find a fair price.

Ever Loved can also more quickly adapt to the diversification of burial options. Between concerns about costs, land use, environmental impact and connection to family and nature, many are looking beyond caskets. Cremation became more popular than burial in the U.S. in 2017. Liquid cremation is now legal in 18 states, and Washington just began allowing body composting.

“We’re seeing a lot of independent providers popping up to do everything from turning your loved one’s ashes into a diamond ring to shooting their ashes into space to planting them under a tree in the forest,” says Johnston. Any single funeral home is unlikely to offer the breadth customers are looking for. “Our goal is to make all of your options available to you in an easily digestible format.”

Ever Loved’s business is protected by the FTC’s Funeral Rule that bars mortuaries from refusing or charging extra to handle a casket or urn purchased elsewhere. That means Ever Loved customers can combine shopping online with in-person memorial services from a local funeral home. Still, it’s a tough business. Startups like HaloLife, Clarity and After I Go have all shut down. Most others merely offer memorial sites, or funeral home search engines.

That means Ever Loved’s biggest competitors, beyond the standard just accepting the local mortuary’s prices, are Google and Amazon. Often they surface the same prices as Ever Loved with comparable shipping, though Google could sometimes find a slight discount by buying straight from the manufacturer, while Amazon was missing some top brands. Costco and Walmart sell funeral products too. But Johnston says “many people don’t feel like generic, mass-market stores are the appropriate place to purchase funeral products.” I agree it might feel disrespectful buying an urn from the same place you get toilet paper.

“We also put a huge focus on customer service, which you don’t get at Walmart, Costco or Amazon,” Johnston tells me. “When you’re grieving and spending thousands of dollars, we’ve found that this is very important.”

As the demographic planning funerals gets more tech-savvy over time and want personalized farewells rather than cookie-cutter conclusions, there’s a chance to change the status quo. Discussing death is becoming less taboo. Being smart about paying for it should too.