A jury will soon decide whether former Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes is guilty of a federal crime. But the deeper public policy questions that Theranos raised remain unanswered. How did a startup built on a technology that never worked grow to a valuation of $9 billion? How was the company able to conceal its fraud for so long? And what, if anything, can be done to prevent the next Theranos before it grows large enough to cause real harm—and burns capital that could have been invested in genuine innovations? I explore these questions in a forthcoming paper in the Indiana Law Journal titled Taming Unicorns.

While Theranos was publicly exposed in October 2015 by Wall Street Journal investigative reporter John Carreyrou, insiders knew that it was committing fraud many years earlier. For example, in 2006, Holmes gave a demo of an early prototype blood test to Novartis executives and faked the results when the device malfunctioned. When Theranos’ CFO confronted Holmes about the incident, she fired him. In 2008—roughly seven years before Carreyrou’s exposé—Theranos board members learned that Holmes had misled them about the company’s finances and the state of its technology.

Over time, a remarkable number of people, both inside and outside the company, began to suspect that Theranos was a fraud. An employee at Walgreens tasked with vetting Theranos for a potential partnership wrote in a report that the company was overselling its technology. Physicians in Arizona grew skeptical of the results their patients were receiving, and a pathologist in Missouri wrote a blog post questioning Theranos’ claims about how accurate its devices were. Stanford Professor John Ioannidis published an article in JAMA raising more doubts.

Meanwhile, rumors had spread in the VC community. Bill Maris of Google Ventures (since rebranded as GV) claimed that his fund passed on investing in Theranos in 2013. According to Maris, the firm had sent an employee to take a Theranos blood test at Walgreens. The employee was asked to give more than the single drop of blood that Theranos claimed its devices needed. After he refused a conventional venous blood draw, he was told to come back to give more blood.

So why did none of these doubts slow Theranos’ fundraising? Part of the answer is that it was a private company, and it’s nearly impossible to bet against private companies.

Until the last decade, most startups that grew to become valuable businesses chose to become public companies. Late-stage startups with reported valuations over $1 billion used to be so rare that VC Aileen Lee dubbed them “unicorns” in a 2013 article in TechCrunch. Back then, there were only 39 startups claiming billion-dollar valuations. By 2021, despite the surge in companies going public through SPACs, the number of unicorns had passed 800.

The rise of unicorns has been accompanied by corporate misconduct scandals. Of course, public companies commit misconduct too. Research hasn’t yet established whether unicorns are systematically more prone to commit misconduct than comparable public companies. However, we do know that the opportunity to profit from information about a company by trading its securities creates incentives to uncover misconduct. Since the securities of private companies aren’t widely traded, it’s easier for private company executives to conceal misconduct.

Consider the electric truck company Nikola, formerly a unicorn. In 2020, Nikola went public through a SPAC. Once it was public, short seller Nathan Anderson decided to investigate and ultimately issued a report alleging a pattern of corporate misconduct. He showed that a video Nikola had produced with its prototype truck traveling at high speed was staged—Nikola had towed the truck to the top of a hill and filmed it rolling downhill in neutral. After Anderson released his report, the SEC and federal prosecutors launched investigations into whether the Nikola misled investors. Its stock price lost more than half of its value. In 2021, Nikola’s CEO Trevor Milton was charged by the SEC and indicted by a federal grand jury. Nikola wouldn’t have been exposed so soon if it had stayed private.

Securities regulation restricts both the sale and resale of private company stock in the name of investor protection. Startups usually attach a contractual right of first refusal to their shares, which effectively requires employees to get the company’s permission to sell. Many late-stage startups practice “selective liquidity”: allowing key employees to cash out in private placements, while preventing a robust market from emerging. Consequently, those who have information about private company misconduct have little incentive to publicize it—even though the Supreme Court has held that an investor who trades on information shared for the purpose of exposing fraud can’t be convicted of insider trading.

VCs might seem well-positioned to police unicorn misconduct. But their asymmetric risk preferences undermine their incentive to expose wrongdoing. VCs invest their funds in a portfolio of startups and expect that most bets will generate modest or negative returns, and only a small number will grow exponentially. The outsize growth of the few successful startups will offset the losses of the balance of the portfolio. For VCs, the difference between a startup that implodes in scandal and the many startups that fail to develop a product or find a market is insignificant.

Venture investing is an auction with a winner’s curse problem. Startups pitch to many VC firms in each fundraising round, but they only need to accept funding from one bidder. In public capital markets, if most investors decide that a company is fraudulent or excessively risky, its stock price will decline. In VC markets however, if most investors decide that a startup is fraudulent, the startup can still raise funds from a credulous contrarian. VCs who pass won’t share their negative assessment with the public because they want to maintain a founder-friendly reputation. Maris only told the press that GV had passed on Theranos after Carreyrou’s article.

Congress and the SEC could strengthen deterrence of unicorn misconduct by creating a market for trading private company securities, in three steps.

First, the regulations constraining the secondary trading of private company securities should be liberalized. The SEC should eliminate Rule 144’s holding period for resales as to accredited investors—the individual and institutional investors that the SEC deems sophisticated and most able to bear risk. Congress should eliminate section 12(g)’s requirement that effectively forces companies to go public if they acquire 2,000 record shareholders who are accredited investors—a rule that leads private companies to limit trading.

Second, the SEC should attach a regulatory most favored nation (MFN) clause to all securities sold through the safe harbors commonly used for private placements. An MFN clause would require that, if a company allows any of its securities to be resold, it must allow all its securities to be resold, as long as the resale is otherwise legal. A regulatory MFN clause would ban the practice of selective liquidity and nudge companies to allow their shares to be traded.

Third, the SEC should require that all private companies that let their securities be widely traded make limited public disclosures about their operations and finances. A limited disclosure mandate would protect investors by ensuring they had basic information about the companies in which they could invest, without saddling unicorns with the costly disclosure obligations placed on public companies.

The net effect of these reforms would be to create a robust market for trading unicorn stock among accredited investors. Most large, private companies would likely decide to allow their shares to be traded. Short sellers, analysts, and financial journalists would be attracted to the markets. Their investigations would strengthen deterrence of unicorn misconduct. The limited disclosure mandate, combined with the requirement that investors be accredited, would protect investors.

When large, private companies commit misconduct, the natural response is to increase the penalty for the underlying misconduct, not to interfere with the tradability of the company’s securities. But the problem isn’t lax penalties. Holmes is facing 20 years in prison—a punishment more brutal than anyone deserves. The problem is that penalties only work when wrongdoers expect to be caught. Trading creates incentives to expose misconduct faster.

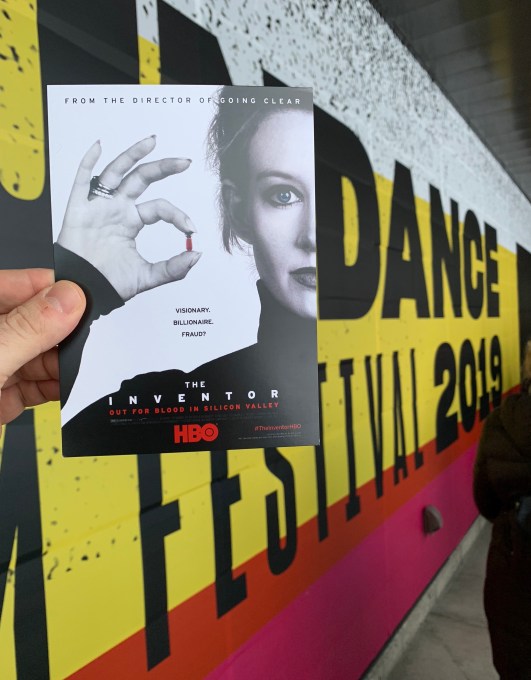

“The Inventor: Out For Blood In Silicon Valley” juxtaposes truthful interviews with the employees who eventually rebelled against Holmes with footage and media appearances of her blatantly lying to the world. It manages to stick to the emotion of the story rather than getting lost in the scientific discrepancies of Theranos’ deception.

“The Inventor: Out For Blood In Silicon Valley” juxtaposes truthful interviews with the employees who eventually rebelled against Holmes with footage and media appearances of her blatantly lying to the world. It manages to stick to the emotion of the story rather than getting lost in the scientific discrepancies of Theranos’ deception.