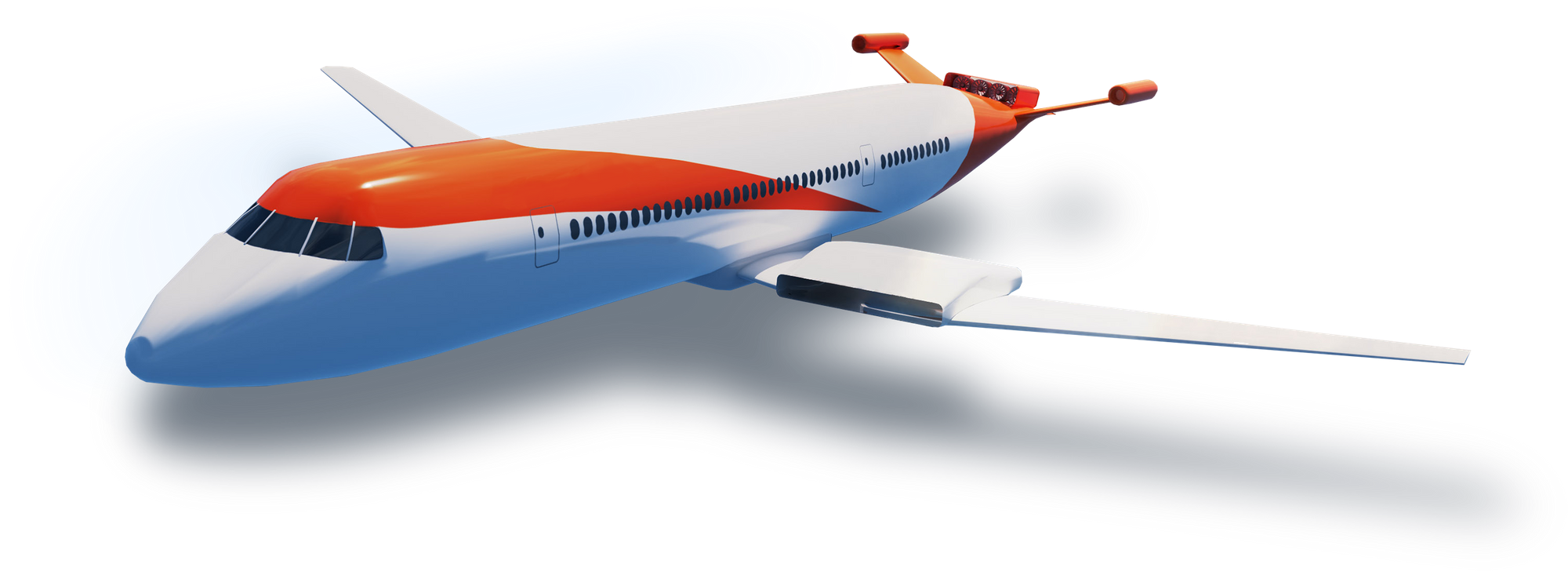

Eviation’s Alice electric aircraft took off for the first time yesterday, teasing a future in which regional flights of hundreds of miles will be done with zero emissions and a lot less noise. It’s still a ways off, but today’s demonstration shows it’s at least just a matter of time and money.

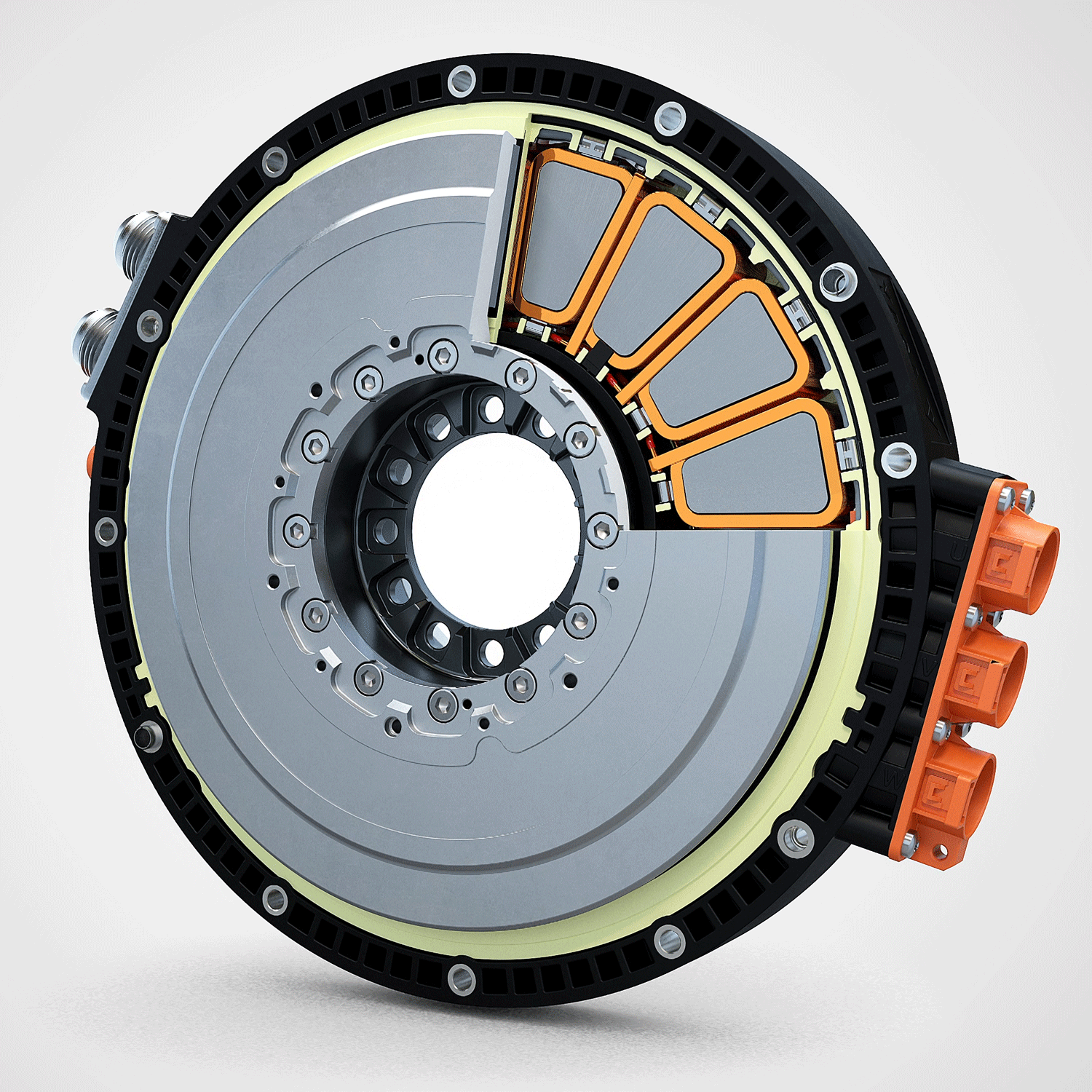

The Alice is a prototype of what will eventually be a passenger plane capable of carrying around 2,500 pounds total, which equates to 6-10 people and their luggage depending on how you want to break it down. It’s powered by a pair of MagniX engines — that company just scooped up $74 million from NASA to develop more of them — and a hefty battery system from AVL. It has a max air speed of about 260 knots.

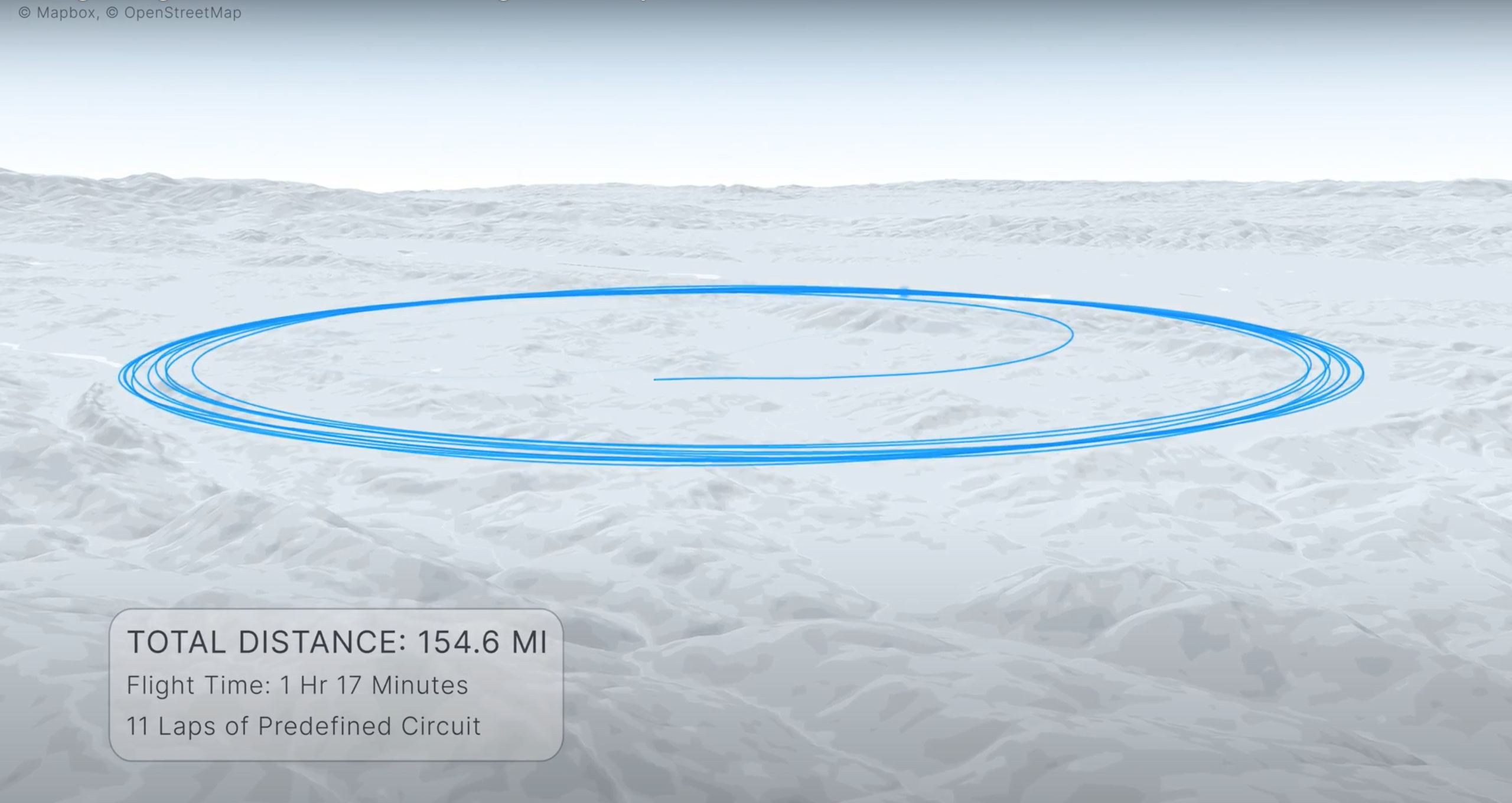

For the test flight, it took off from an airport in central Washington, ascended to 3,500 feet, then landed again, for a total flight time of 8 minutes. That’s just about enough to show that the aircraft can do what it’s meant to do, but it’s still a long ways to full passenger flights.

“Today’s first flight provided Eviation with invaluable data to further optimize the aircraft for commercial production. We will review the flight data to understand how the performance of the aircraft matched our models,” Eviation CEO and President Gregory Davis told TechCrunch.

This wasn’t just a big press event to show off their shiny new aircraft — it was an incredibly important validation of what had, until left the tarmac, been an aircraft only in theory. This flight will be followed by more test flights as they explore the limits of the aircraft and how it performs under a variety of conditions.

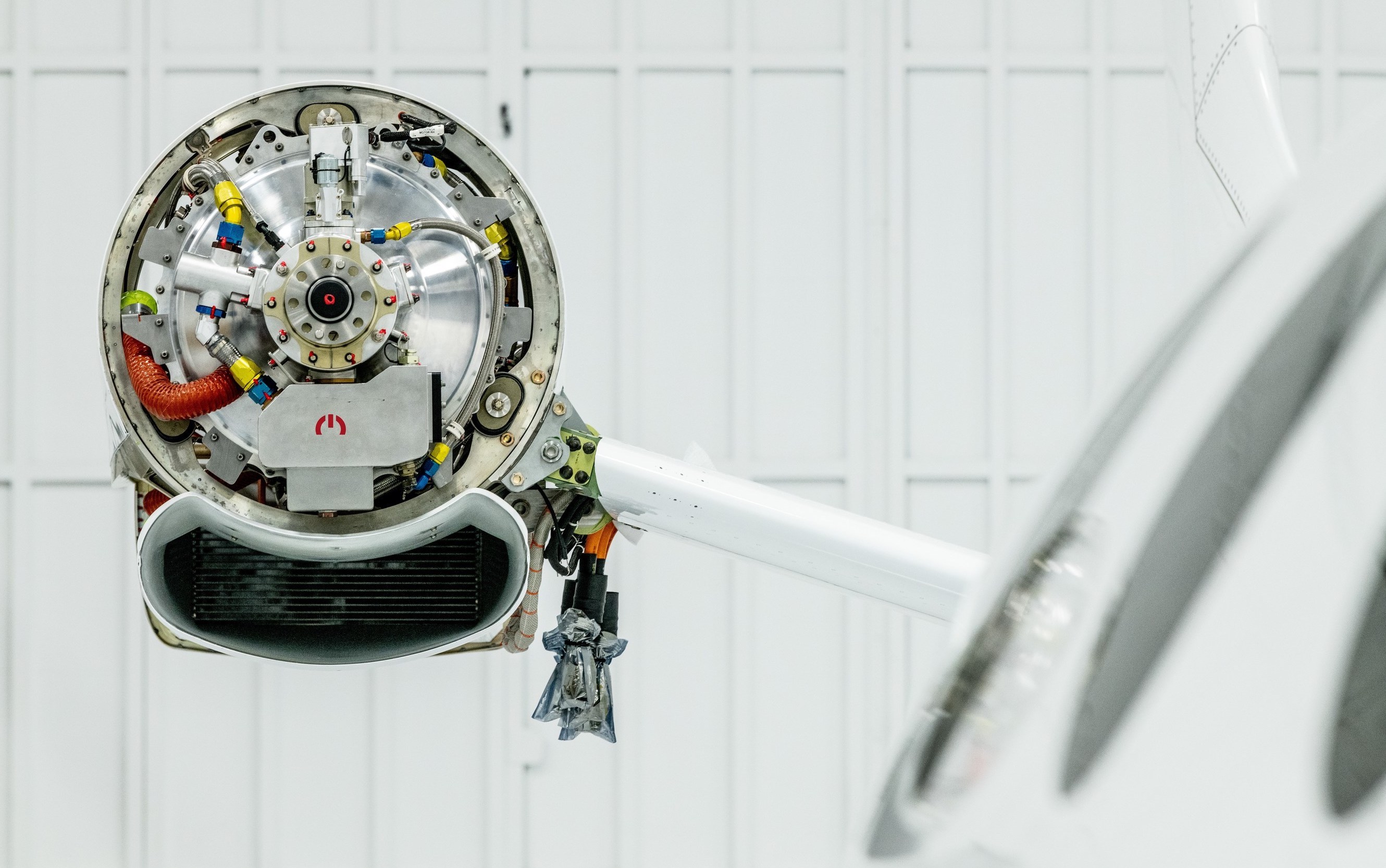

A magniX Electric Propulsion Unit (EPU) in the Alice aircraft.

Of course ultimately they’ll need to commit to a design and certify it, and Davis said that 2025 is their target for performing tests with the production prototypes of the aircraft. These things move slow by design — there’s a reason air travel is so safe.

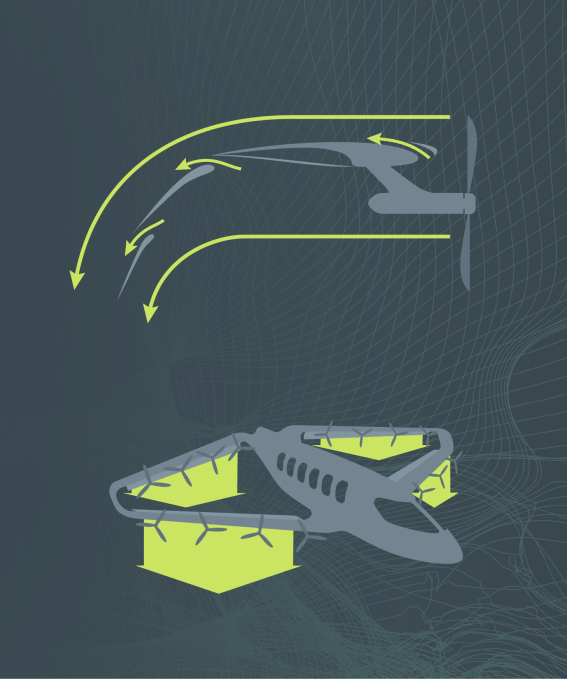

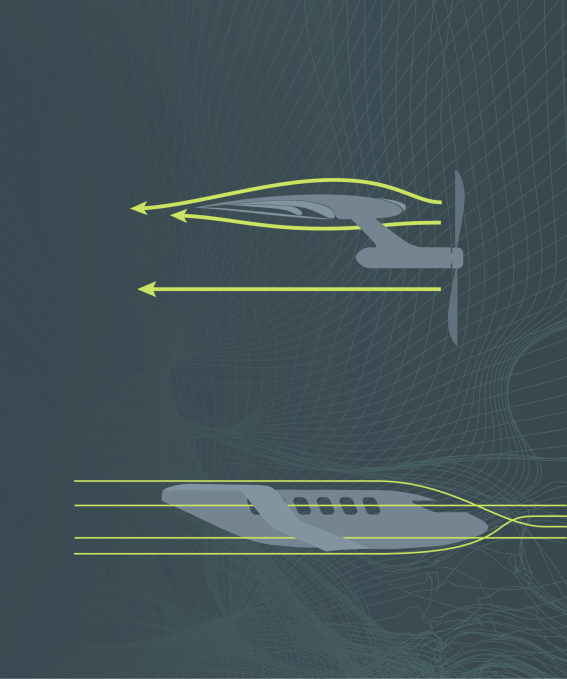

What Eviation (and many other ambitious electric and hybrid flight companies) envision is an activation of many new points of travel, like regional airports primarily used by cargo companies and private plane owners. Cheap, clean flights between these smaller hubs could simplify both commutes and cargo.

Why don’t we use them already, you ask? Gas-powered planes are loud and the logistics of fueling, pickup, and other infrastructure don’t always work out. Smaller, quieter planes delivering packages to a more local delivery hub might make sense. Investment from municipal or county governments to reactivate a bit of disused but valuable infrastructure could help defray the cost of updating regional airports as well.

“Electric aviation opens up more opportunities to connect communities where noise concerns have been a deterrent to flights, and restrict operating hours,” Davis said.

As for passengers, we’ll see how the new transport network plays out — maybe you’ll land and get straight into a robotaxi by the time Eviation is flying in your neck of the woods. It should also be a quieter ride on the inside, though don’t expect total silence.

Left to right: Steve Crane, Test Pilot; Richard F. Chandler, Chairman, Clermont Group, Majority Shareholder of Eviation; ; Greg Davis, President and CEO of Eviation.

The company declined to speculate as to the timing of its first major flight, which I defined as 50 miles or more, saying that all depends on the testing and certification process. Which is fair — you don’t just take the only prototype out for a spin when millions of dollars are riding on it.

And there are definitely customers waiting at the door: it might be a few years before Alice (or its successor — Bob?) is operational, but more than 100 aircraft have already been reserved.

Cape Air and Global Crossing Airlines ordered 75 and 50 aircraft respectively; both are regional airlines that could use Alice type electric craft to cover a majority of their flights. It’s a big investment, but the fuel and potentially maintenance savings would be enormous. DHL Express has also ordered a dozen planes, clearly preferring to dip its toe into the pool first.

The electric aviation space is heating up, and companies are finally moving past the concept stage and into real testing — you can expect continued growth and diversity in the next few years as the industry further embraces a greener, quieter future.

Eviation’s all-electric Alice aircraft makes its maiden flight by Devin Coldewey originally published on TechCrunch