Both as a term and as a financial product, “buy now, pay later” has become mainstream in the past few years. BNPL has evolved to assume various forms today, from small-ticket offerings by fintechs on consumer checkout platforms and marketplaces, to closed-loop products offered on marketplaces such as Amazon Pay Later (which they are now extending for outside use as well). You can also see some variants offered by companies that want to expand the scope of consumption and consumer credit.

Globally, BNPL has seen the most growth in the consumer segment and has driven retail consumption and lending over the past few years. Consumer BNPL offerings are a good alternative to credit cards, especially for people who do not have a credit history and can’t get credit from banks. That said, a specific vertical of BNPL products is gaining traction — one targeted toward small and medium enterprises (SMEs). This new vertical is known as “SME BNPL.”

BNPL can be particularly useful when flow-based underwriting or transaction-based underwriting is used to offer credit to small businesses.

B2B commerce in India is moving online

E-commerce has seen tremendous growth in India over the past decade. Skyrocketing smartphone and internet penetration led to rapid growth in e-commerce across large cities and smaller towns alike. Consumer credit has also taken off in parallel as credit cards and digital lending spurred credit-based consumption across offline and online stores.

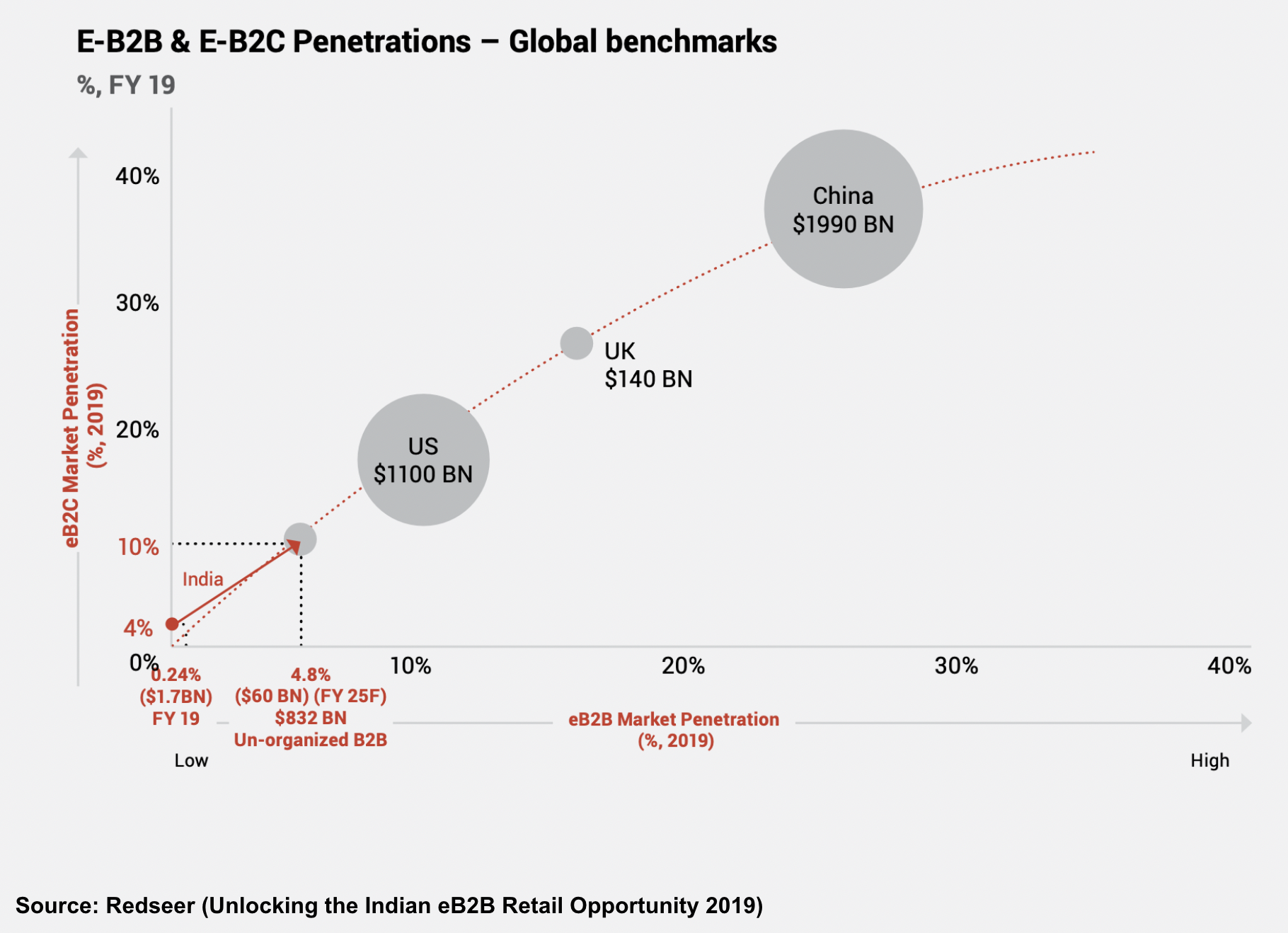

However, the large B2B supply chain enabling the burgeoning retail market was plagued by bottlenecks and inefficiencies because it involved a plethora of intermediaries and streamlining became a big problem. A number of tech players responded by organizing the previously disorganized B2B commerce market at various touch points, inserting convenience, pricing and easier product access through tech-enabled logistics and a modern supply chain.

Image Credits: Redseer

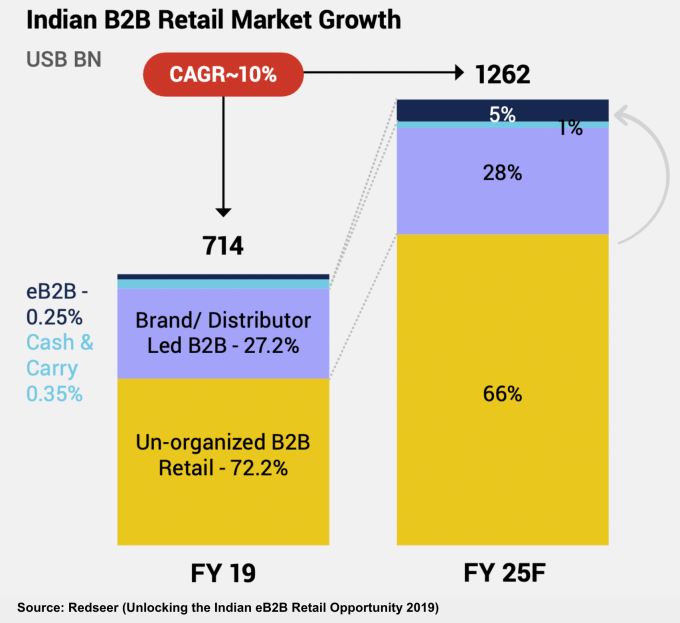

India’s B2B e-commerce space has developed rapidly since 2020. Small businesses have moved from using paper to smartphone apps for running a significant part of their day-to-day business, leading to widespread disruption in how businesses transact today. The COVID-19 pandemic also forced small businesses, which were earlier using physical means to procure goods and services, to try new and online models to conduct their affairs.

Image Credits: Redseer

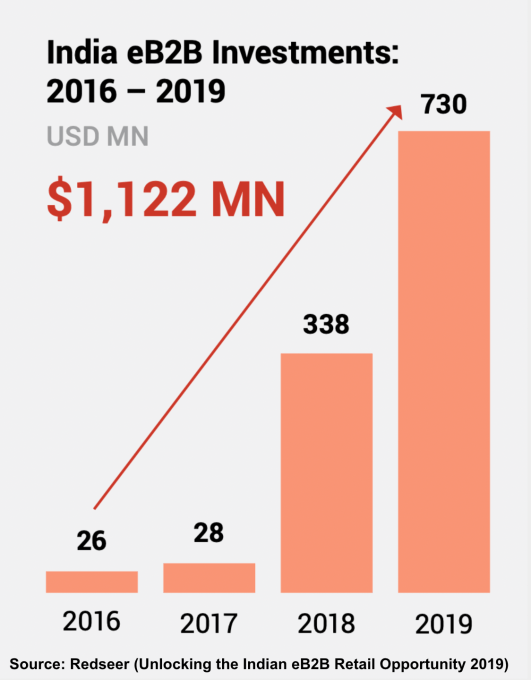

Moreover, the Indian government’s widespread promotion of an instant payments system in the form of the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) has changed how people send money to each other or pay merchants for their goods and services. The next step for solving the digital B2B puzzle is to embed credit inside every transaction and invoice.

Image Credits: Redseer

If we compare online B2B transactions to the offline world, there is only one missing link: The terms offered to small businesses by their supplier/distributor or vendor. Businesses, unlike consumers, must buy goods and services to eventually trade them, or add value and sell to consumers or others down the value chain. This process is not immediate and has a certain time cycle attached.

The longer sales cycle means many small businesses require credit payment terms when buying inventory. As B2B commerce scales and grows through digital means, a BNPL product that caters to the needs of SMEs can support their growth and alleviate the burden on their cash flows.

How does consumer BNPL differ from SME BNPL?

An SME BNPL product is a purchase financing product for small businesses transacting with suppliers, distributors, aggregator platforms or B2B marketplaces.