Patreon provides business infrastructure to independent content creators: people making videos, music, podcasts, paintings, comics, games, magazines and other forms of media for fans online. It helps them turn the small subset of superfans within their broader fan base into paying monthly patrons and manage relationships with those patrons across the web. Patreon is angling to become the dominant platform for creators to build these membership businesses, a position from which it could expand into other products and services for creators.

In this section of the EC-1, I am digging into the structure, performance and health of Patreon as a business. The sections are organized as follows:

- Business model

- Revenue

- User metrics

- New revenue streams

- Costs and efficiencies

- Mergers and acquisitions

- Investors and fundraising

My analysis of Patreon’s product, competitors, and overarching thesis have been spun out as their own articles.

Reading time for this article is about 20 minutes. Feature illustration by Bryce Durbin / TechCrunch.

Business model

Patreon’s business model is straightforward, though it is becoming more complex. It charges creators 10 percent of their revenues through the platform, which is divided into a 5 percent platform fee and a 5 percent payment processing fee. Patreon has always had a flat 5 percent platform fee, but its payment processing fees have varied in the past.

Patreon has shifted strategy, no longer acting as a marketplace connecting fans and creators but as a SaaS platform with a suite of tools for creators. Rather than viewing its fees as a marketplace rake, a better analogy is to the commission model akin to that of a talent manager, agent or record label. Patreon’s incentives are directly aligned with its customers’ goal of generating more income from their fans.

That simple model will get more complicated, as Patreon is poised to introduce additional commission fees in exchange for access to some new functionality and services. Plus, the company acquired two startups last year (Memberful and Kit), which each come with their own business models.

Revenue

On January 23rd, Patreon announced it expects to process more than $500 million in payments in 2019. That would put the company’s 2019 revenue from its core Patreon platform at north of $50 million, given its 10 percent cut.

Back in May 2018, CEO Jack Conte said in a video that they would process $300 million in payments that year, implying roughly $30 million in revenue for 2018. That was twice the $150 million they processed in 2017 (the payment fee was variable until 2018, so the 10 percent assumption doesn’t hold for 2017, but I assume revenue was in the $12-15 million range).

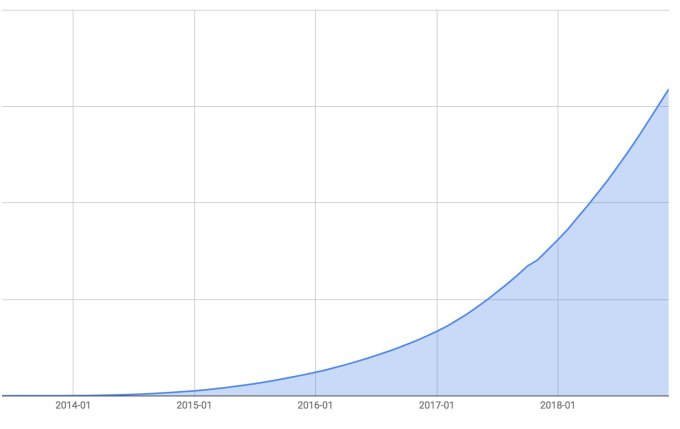

Graph of payments processing volume by Patreon since founding, shared on Twitter on February 6, 2018 by Patreon CEO Jack Conte

None of these figures include revenue from Memberful or Kit. Kit’s revenue is likely a rounding error by comparison, and there is no longer any team working on it or resources allocated to developing it further.

In contrast, Conte told me calling Memberful a rounding error would be “way off” and that it’s a product with “incredible product-market fit and incredible traction” whose revenue doesn’t look tiny next to Patreon’s. TechCrunch’s Josh Constine reported it had 500 paying customers and seven employees at the time of the acquisition. I haven’t found helpful data to use in estimating Memberful’s revenue, so whether this is $3 million or $5 million or another amount, I don’t know.

Is Patreon profitable? “Yeah, we’ve a ways to go there,” said Conte. After multiple years of trying to figure out its long-term business model and role within the online creator ecosystem, Patreon has clarified that creators are its customers and it will generate new revenue streams by offering new products and services to them.

User metrics

Creators

Patreon reports the total number of creators earning at least $1 on its platform as “over 100,000,” but they have been using that statistic since mid-2018. The independent website Graphtreon, which estimates Patreon data using the company’s API, says the total number of creators with at least one patron is 132,500.

Based on this same Graphtreon data set, the number of creators increased 105 percent year-over-year in 2017 (to 92,500), but then only 39 percent in 2018 (to 129,000). Patreon’s Head of Communications said the correct 2018 growth rate for creators is “slightly over 50 percent growth.”

Revenue almost doubled over the last year, and revenue is tied to creator earnings. If revenue growth is holding steady while creator growth is slowing, it implies Patreon is adding fewer small creators who don’t generate much income, but is still gaining strong traction among more established creators who do.

Creator churn tightly correlates to creator income on the platform. People don’t walk away from a meaningful source of income, but they will walk away if they have been trying to gain patrons for weeks and only have $10 to show for it. A large number of creators join Patreon before they have a fan base — they see successful creators on Patreon and mistakenly attribute that success to joining Patreon rather than bringing a pre-existing fan base to it. They churn after a few months of gaining little to no financial backing.

From the data Patreon agreed to show me during my research, I can tell you that the annual churn rate of Patreon creators drops under 1 percent for those generating $500 per month in revenue through the platform. The greater the income, the lower the churn, and after $1,000 per month in particular, it is very rare for creators to leave the platform at all.

$1K Creators

Given those churn metrics, Patreon’s team now measures the company’s progress by two KPIs: 1) the number of creators earning $1,000+ per month and 2) the total amount of money those creators are earning through Patreon.

This focus on $1,000+ per month creators (which I’ll refer to as “$1K Creators”) likely derives from their stickiness as customers, the disproportionate contribution they make to Patreon’s revenue and the strategic decision to narrow the platform’s scope to building tools for creators with existing fan bases (not trying to help creators without fan bases get discovered).

These $1K Creators receive 70 percent of the patronage and so generate 70 percent of Patreon’s revenue (or ~$35 million in 2019). Given the extent to which content is a hits business, in which the superstars in each field capture a massively disproportionate percentage of the economics, Patreon is less top-heavy than one might otherwise expect. While it has many $50,000+ per month creators, and indeed its single highest-earning creator — earning roughly $400-500,000 per month by my estimate — accounts for nearly 1 percent of all money flowing through the platform, Patreon’s dominant revenue source is creators earning between $1,000 and $50,000 per month. This is the mid-tail of content creators that the company’s business thesis hinges on.

Patreon doesn’t disclose how many $1K Creators there are, but CEO Jack Conte said “It’s a tiny portion. Because it’s an open platform, we at one point had hundreds and hundreds of thousands of creators who were making $0.” By the estimates of Graphtreon creator Tom Boruta, there are currently more than 4,300 creators making at least $1,000 per month (and more than 9,200 creators making $500+ per month). That small subset — 4,300 out of 132,500 active creators or about 3.2 percent of its customers — is Patreon’s core focus nowadays.

Patrons

In 2018, creators used Patreon to generate income from more than 3 million active patrons. That is a 50 percent year-over-year increase from the 2 million patrons Patreon had processed payments from in 2017. Using data from Second Measure — a firm that tracks billions of anonymized debit and credit transactions from millions of U.S. consumers — Patreon appears to be retaining patrons at a healthy rate. Averaging across several cohorts, 62 percent of first-time patrons on Patreon are still sending payments six months later and 51 percent are still doing so after a year. For comparison, those retention rates are about 10 percent behind Netflix’s best-in-class 73 percent and 66 percent metrics, respectively, but on par with those of Hulu (61 percent at six months and 53 percent at 12 months).

Far from a uniquely San Francisco phenomenon, patrons are geographically distributed too. According to the same Second Measure data set, while New York City leads in (U.S.-based) patrons, San Antonio is the second most common city with 2.2 percent of U.S. transactions, with Austin, Chicago, Houston, Las Vegas, Dallas, Tucson, Colorado Springs and Atlanta all making appearances in the top 20 (a “city” here is a legal jurisdiction, not a metro area). Moreover, Patreon confirmed that 40 percent of all money flowing through Patreon since founding has come from patrons outside the U.S.