Perhaps Mark Zuckerberg obsessed over the wrong bit of history. Or else didn’t study his preferred slice of classical antiquity carefully enough, faced, as he now is, with an existential crisis of ‘fake news’ simultaneously undermining trust in his own empire and in democracy itself.

A recent New Yorker profile — questioning whether the Facebook founder can fix the creation he pressed upon the world before the collective counter-pressure emanating from his billions-strong social network does for democracy what Brutus did to Caesar — touched in passing on Zuckerberg’s admiration for Augustus, the first emperor of Rome.

“Basically, through a really harsh approach, he established two hundred years of world peace,” was the Facebook founder’s concise explainer of his man-crush, freely accepting there had been some crushing “trade-offs” involved in delivering that august outcome.

Zuckerberg’s own trade-offs, engaged in his quest to maximize the growth of his system, appear to have achieved a very different kind of outcome.

Empire of hurt

If you gloss over the killing of an awful lot of people, the Romans achieved and devised many ingenious things. But the population that lived under Augustus couldn’t have imagined an information-distribution network with the power, speed and sheer amplifying reach of the internet. Let alone the data-distributing monster that is Facebook — an unprecedented information empire unto itself that’s done its level best to heave the entire internet inside its corporate walls.

Literacy in Ancient Rome was dependent on class, thereby limiting who could read the texts that were produced, and requiring word of mouth for further spread.

The ‘internet of the day’ would best resemble physical gatherings — markets, public baths, the circus — where gossip passed as people mingled. Though of course information could only travel as fast as a person (or an animal assistant) could move a message.

In terms of regular news distribution, Ancient Rome had the Acta Diurna, A government-produced daily gazette that put out the official line on noteworthy public events.

These official texts, initially carved on stone or metal tablets, were distributed by being exposed in a frequented public place. The Acta is sometimes described as a proto-newspaper, given the mix of news it came to contain.

Minutes of senate meetings were included in the Acta by Julius Caesar. But, in a very early act of censorship, Zuckerberg’s hero ended the practice — preferring to keep more fulsome records of political debate out of the literate public sphere.

“What news was published thereafter in the acta diurna contained only such parts of the senatorial debates as the imperial government saw fit to publish,” writes Frederick Cramer, in an article on censorship in Ancient Rome.

Augustus, the grand-nephew and adopted son of Caesar, evidently did not want the risk of political opponents using the outlet to influence opinion, his great-uncle having been assassinated in a murderous plot hatched by conspiring senators.

The Death of Caesar

Under Augustus, the Acta Diurna was instead the mouthpiece of the “monarchic faction.”

“He rightly believed this method to be less dangerous than to muzzle the senators directly,” is Cramer’s assessment of Augustus’s decision to terminate publication of the senatorial protocols, limiting at a stroke how physical voices raised against him in the Senate could travel and lodge in the wider public consciousness by depriving them of space on the official platform.

Augustus also banned anonymous writing in a bid to control incendiary attacks distributed via pamphlets and used legal means to command the burning of incriminatory writings (with some condemned authors issued with ‘literary death-sentences’ for their entire life’s work).

The first emperor of Rome understood all too well the power of “publicare et propagare.”

It’s something of a grand irony, then, that Zuckerberg failed to grasp the lesson for the longest time, letting the eviscerating fire of fake news rage on unchecked until the inferno was licking at the seat of his own power.

So instead of Facebook’s brand and business invoking the sought-for sense of community, it’s come to appear like a layer cake of fakes, iced with hate speech horrors.

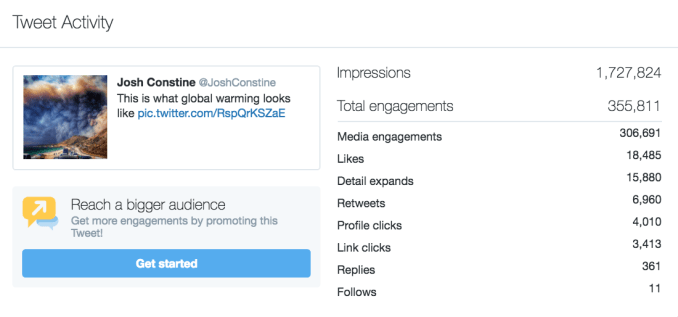

On the fake front, there are fake accounts, fake news, inauthentic ads, faux verifications and questionable metrics. Plus a truck tonne of spin and cynical blame shifting manufactured by the company itself.

There’s some murkier propaganda, too; a PR firm Facebook engaged in recent years to help with its string of reputation-decimating scandals reportedly worked to undermine critical voices by seeding a little inflammatory smears on its behalf.

Publicare et propagare, indeed.

Perhaps Zuckerberg thought Ancient Rome’s bloody struggles were so far-flung in history that any leaderly learnings he might extract would necessarily be abstract, and could be cherry-picked and selectively filtered with the classical context so comfortably remote from the modern world. A world that, until 2017, Zuckerberg had intended to render, via pro-speech defaults and systematic hostility to privacy, “more open and connected.” Before it got too difficult for him to totally disregard the human and societal costs.

Revising the mission statement a year-and-a-half ago, Zuckerberg had the chance to admit he’d messed up by mistaking his own grandstanding world-changing ambition for a worthy cause.

Of course he sidestepped, writing instead that he would commit his empire (he calls it a “community”) to strive for a specific positive outcome.

It’s something of a grand irony, then, that Zuckerberg failed to grasp the lesson for the longest time, letting the eviscerating fire of fake news rage on unchecked until the inferno was licking at the seat of his own power.

He didn’t go full Augustus with the new goal (no ‘world peace’) — but recast Facebook’s mission to: “Give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together.”

There are, it’s painful to say, “communities” of neo-Nazis and white supremacists thriving on Facebook. But they certainly don’t believe in bringing the world closer together. So Facebook’s reworked mission statement is a tacit admission that its tools can help spread hate by saying it hopes for the opposite outcome. Even as Zuckerberg continues to house voices on his platform that seek to deny historical outrages like the Holocaust, which is the very definition of antisemitic hate speech.

“I used to think that if we just gave people a voice and helped them connect, that would make the world better by itself. In many ways it has. But our society is still divided,” he wrote in June 2017, eliding his role as emperor of the Facebook platform, in fomenting the societal division of which he typed. “Now I believe we have a responsibility to do even more. It’s not enough to simply connect the world, we must also work to bring the world closer together.”

This year his personal challenge was also set at “fixing Facebook.”

Also this year: Zuckerberg made a point of defending allowing Holocaust deniers on his platform, then scrambled to add the caveat that he finds such views “deeply offensive.” (That particular Facebook content policy has stood unflinching for almost a decade.)

It goes without saying that the Nazis of Hitler’s Germany understood the terrible power of propaganda, too.

More recently, faced with the consequences of a moral and ethical failure to grapple with hateful propaganda and junk news, Facebook has said it will set up an external policy committee to handle some content policy decisions next year.

But only at a higher and selective appeal tier, after layers of standard internal reviews. It’s also not clear how this committee can be truly independent from Facebook.

Quite possibly it’ll just be another friction-laced distraction tactic, akin to Facebook’s self-serving ‘Hard Questions’ series.

WASHINGTON, DC – APRIL 11: Facebook co-founder, Chairman and CEO Mark Zuckerberg prepares to testify before the House Energy and Commerce Committee on April 11, 2018 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Revised mission statements, personal objectives and lashings of self-serving blog posts (playing up the latest self-forged “accountability” fudge), have done nothing to dim the now widely held view that Facebook specifically, and social media in general, profits off of accelerated outrage.

Cries to that effect have only grown louder this year, two years on from revelations that Kremlin election propaganda maliciously targeting the U.S. presidential election had reached hundreds of millions of Facebook users, fueled by a steady stream of fresh outrages found spreading and catching fire on these “social” platforms.

Like so many self-hyping technologies, social media seems terribly deceptively named.

“Antisocial media” is, all too often, rather closer to the mark. And Zuckerberg, the category’s still youthful warlord, looks less “harshly pacifying Augustus” than modern day Ozymandias, forever banging on about his unifying mission while being drowned out by the sound and fury coming from the platform he built to programmatically profit from conflict.

And still the young leader longs for the mighty works he might yet do.

Look on my works, ye mighty…

For all the positive connections flowing from widespread access to social media tools (which of course Zuckerberg prefers to fix on), evidence of the tech’s divisive effects are now impossible for everyone else to ignore: Whether you look at the wildly successful megaphoning of Kremlin propaganda targeting elections and (genuine) communities by pot stirring across all sorts of identity divides; or algorithmic recommendation engines that systematically point young and impressionable minds toward extremist ideologies (and/or brain-meltingly ridiculous conspiracy theories) as an eyeball-engagement strategy for scaling ad revenue in the attention economy. Or, well, Brexit.

Whatever your view on whether or not Facebook content is actually influencing opinion, attention is undoubtedly being robbed. And the company has a long history of utilizing addictive design strategies to keep users hooked.

To the point where it’s publicly admitted it has an over-engagement problem and claims to be tweaking its algorithmic recipes to dial down the attention incursion. (Even as its engagement-based business model demands the dial be yanked back the other way.)

Facebook’s problems with fakery (“inauthentic content” in the corporate parlance) and hate speech — which, without the hammer blow of media-level regulation, is forever doomed to slip through Facebook’s one-size-fits-all “community standards” — are, it argues, merely a reflection of humanity’s flaws.

So it’s essentially asking to be viewed as a global mirror, and so be let off the moral hook. A literal vox populi — warts, fakes, hate and all.

Zuckerberg created the most effective tool for spreading propaganda the world has ever known without — so he claims — bothering to consider how people might use it.

It was never selling a fair-face, this self-serving, revisionist hot-take suggests; rather Facebook wants to be accepted as, at best, a sort of utilitarian plug that’s on a philanthropic, world-spanning infrastructure quest to stick a socket in everyone. Y’know, for their own good.

“It’s fashionable to treat the dysfunctions of social media as the result of the naivete of early technologists who failed to foresee these outcomes. The truth is that the ability to build Facebook-like services is relatively common,” wrote Cory Doctorow earlier this year in a damning assessment of the Facebook founder’s moral vacuum. “What was rare was the moral recklessness necessary to go through with it.”

Even now Zuckerberg is refusing the moral and ethical burden of editorial responsibility for the content his tools auto-publish and algorithmically amplify, every instant of every day, using proprietary information-shaping distribution hierarchies that accelerate machine-selected clickbait through the blood-brain barrier of 2.2 billion-plus users.

These algorithmically prioritized comms are positioned to influence opinion and drive intention at an unprecedented, global scale.

Asked by the New Yorker about the inflammatory misinformation peddled by InfoWars conspiracy theorist and hate speech “preacher,” Alex Jones, earlier this year, Zuckerberg’s gut instinct was to argue again to be let off the hook. “I don’t believe that it is the right thing to ban a person for saying something that is factually incorrect,” was his disingenuous response.

It was left to the journalist to point out InfoWars’ malicious disinformation is rather more than just factually incorrect.

Facebook has taken down some individual InfoWars videos this year, in its usual case by case style, where it deemed there was a direct incitement to violence. And in August it also pulled some InfoWars pages (“for glorifying violence, which violates our graphic violence policy, and using dehumanizing language to describe people who are transgender, Muslims and immigrants, which violates our hate speech policies”).

But it has certainly not de-platformed the professional purveyor of hateful conspiracy theories who sells supplements alongside his attention-grabbing lies.

One academic study, published two months ago, found much of the removed InfoWars content had managed to move “swiftly back” onto the Facebook platform. Like radio and silence, Facebook hates a content vacuum.

The problem is its own platform also sells stuff alongside attention-grabbing lies. So Jones is just the Facebook business model if it could pull on a blue suit and shout.

“Senator, we run ads”

It’s clear that Facebook’s adherence to a rules-based, reactive formula for assessing speech sets few if any meaningful moral standards. The company has also preferred to try offloading tricky decisions to third-party fact checkers and soon a quasi-external committee — a strategy that looks intended to sustain the suggestive lie that, at base, Facebook is just a “neutral platform.”

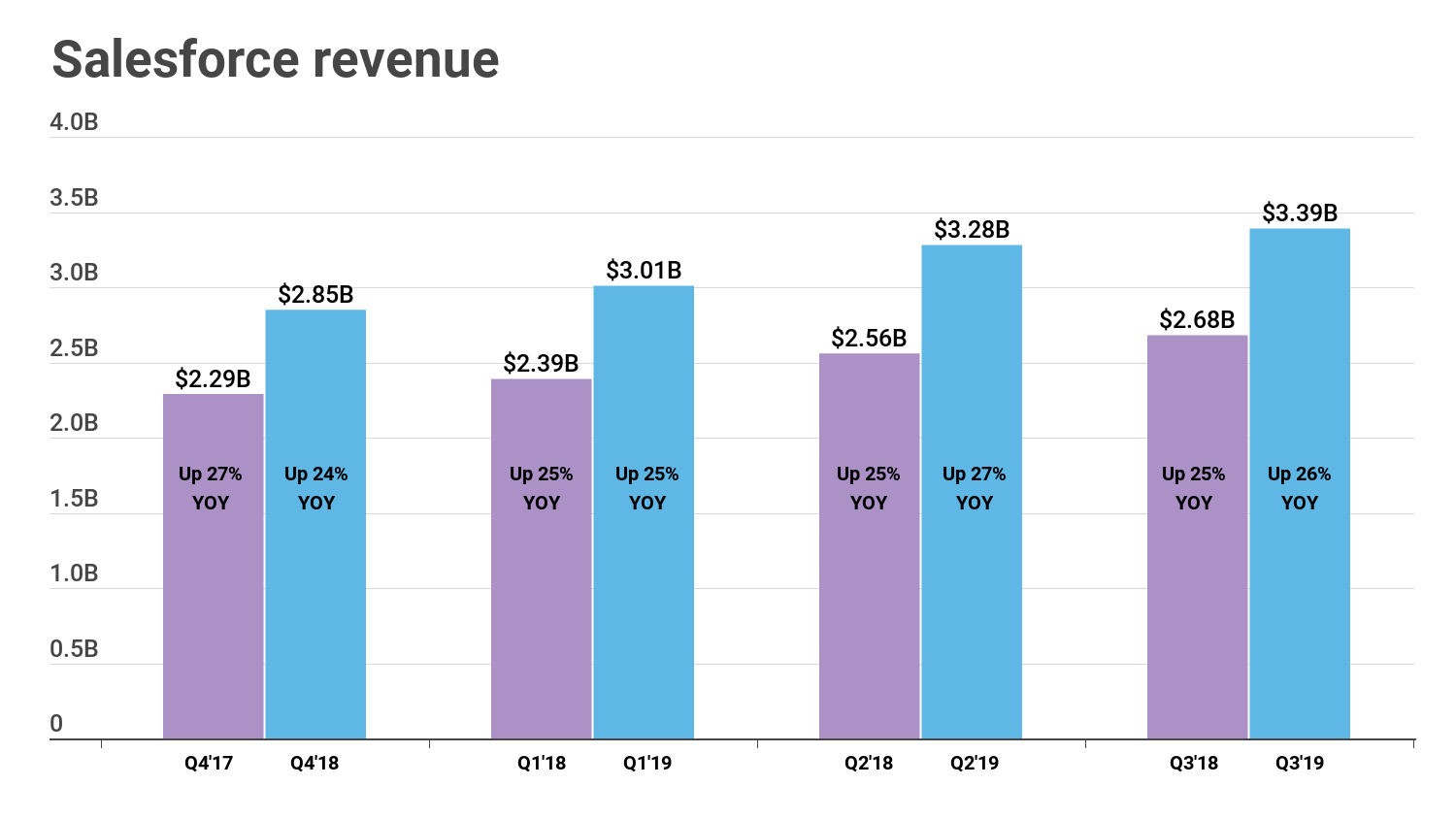

Yet Zuckerberg’s business is the business of influence itself. He admits as much. “Senator, we run ads,” he told Congress this April when asked how the platform turns a profit.

If the ads don’t work that’s an awful lot of money being pointlessly poured into Facebook’s coffers.

At the same time, the risk of malicious manipulation of Facebook’s machinery of mass manipulation is something the company claims it simply hadn’t thought of until very, very recently.

That’s the official explanation for why senior executives failed to pay any mind to the tsunami of politically charged propaganda blooming across its U.S. platform, yet originating in Saint Petersburg and environs.

An astute political operator like Augustus was entirely alive to the risks of political propaganda. Hence making sure to keep a lid on domestic political opponents, while allowing them to let off steam in the Senate where a wider audience wouldn’t hear them.

Zuckerberg, by contrast, created the most effective tool for spreading propaganda the world has ever known without — so he claims — bothering to consider how people might use it.

That’s either radical stupidity or willful recklessness.

Zuckerberg implies the former. “I always believed people are basically good,” he wrote in his grandiose explainer on rethinking Facebook’s mission statement last year.

Though you’d think someone with a fascination for classical antiquity, and a special admiration for an emperor whose harsh trade-offs apparently included arranging the execution of his own grandson, might have found plenty to test that theory to a natural breaking point.

Safe to say, such a naive political mind wouldn’t have lasted long in Ancient Rome.

But Zuckerberg is no politician. He’s a new-age ad salesman with a crush on one of history’s canniest political operators — who happened to know the power and value of propaganda. And who also knew that propaganda could be deadly.

If you imagine Facebook’s platform as a modern day Acta Diurna — albeit, one updated continuously, delivered direct to citizens’ pockets, and with no single distributed copy ever being exactly the same — the organ is clearly not working toward any kind of societal order, crushing or otherwise.

Under Zuckerberg’s programmatic instruction, Facebook’s daily notices are selected for their capacity to emotionally tug at the individual. By design the medium agitates because the platform exists to trade attention.

It’s really the opposite of “civilization building.” Outrage and tribalism are grist to the algorithmic mill. It’s much closer to the tabloid news mantra — of “if it bleeds it leads.”

But Facebook goes further, using “free speech” as a cloaking mechanism to cross the ethical line and conceal the ugly violence of a business that profits by ripping up the social compact.

The speech-before-truth philosophy underpinning Zuckerberg’s creation intrinsically works against the civic, community values he claims to champion. So at bottom, there’s yet another fake: no “global community” inside the walled garden, just a globally scaled marketing empire that’s had raging success in growing programmatic ad sales by tearing genuine communities apart.

Here confusion and anger reign.

The empire of Zuckerberg is a drear domain indeed.

One hundred cardboard cutouts of Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg stand outside the US Capitol in Washington, DC, April 10, 2018.

Advocacy group Avaaz is calling attention to what the groups says are hundreds of millions of fake accounts still spreading disinformation on Facebook. (Photo: SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images)

Fake news of the 1640s

Might things have turned out differently for Facebook — and, well, for the world — if its founder had obsessed over a different period in history?

The English Civil War of the 1640s has much to recommend it as a study topic to those trying to understand and unpick the social impacts of the hyper modern phenomenon of social media, given the historical parallels of society turned upside during a moment of information revolution.

It might seen counterintuitive to look so far back in time to try to understand the societal impacts of cutting-edge communications technologies. But human nature can be surprisingly constant.

Internet platforms are also socio-technical tools, which means ignoring human behavior is a really dumb thing to do.

As the inventor of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, said recently of modern day anthropogenic platforms: “As we’re designing the system, we’re designing society.”

The design challenge is all about understanding human behaviour — so you know how and where to place your ethical guardrails.

Rather than, per the Zuckerberg fashion, embarking on some kind of a quixotic, decade-plus quest to chase a grand unifying formula of IFTTT reaction statements to respond consistently to every possible human (and inhuman) act across the globe.

Mozilla’s Mitchell Baker made a related warning earlier this year, when she called for humanities and ethics to be baked into STEM learning, saying: “One thing that’s happened in 2018 is that we’ve looked at the platforms, and the thinking behind the platforms, and the lack of focus on impact or result. It crystallised for me that if we have Stem education without the humanities, or without ethics, or without understanding human behaviour, then we are intentionally building the next generation of technologists who have not even the framework or the education or vocabulary to think about the relationship of Stem to society or humans or life.”

What’s fascinating about the English Civil War to anyone interested in current day Internet speech versus censorship ethics trade-offs, is that in a similar fashion to how social media has radically lowered the distribution barrier for online speech, by giving anyone posting stuff online the chance of reaching a large audience, England’s long-standing regime of monarchical censorship collapsed in 1641, leading to a great efflorescence of speech and ideas as pamphlets suddenly and freely poured off printing presses.

This included an outpouring of radical political views from groups agitating for religious reforms, popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, common ownership and even proto women’s rights — laying out democratic concepts and liberal ideas centuries ahead of the nation itself becoming a liberal democracy.

But, at the same time, pamphlets were also used during the English Civil War period as a cynical political propaganda tool to whip up racial and sectarian hatred, most markedly in the parliament’s fight against the king.

Especially vicious hate speech was directed at the Irish. And historians suggest anti-Irish propaganda helped fuel the rampage that Cromwell’s soldiers went on in Ireland to crush the rebellion, having been fed a diet of violent claims in uncensored pamphlet print — such as that the Irish were killing and eating babies.

For a modern day parallel of information technology charging up ethnic hate you only have to look to Facebook’s impact in Myanmar where its platform was appropriated by military elements to incite genocide against the minority Rohingya population — leading to terrible human rights abuses in the modern era. There’s no shortage of other awful examples either.

“There are genuine atrocities in Ireland but suddenly the pamphleteers realise that this sells and suddenly you get a pornography of violence when everyone is rushing to put out these incredibly violent and unpleasant stories, and people are rushing to buy them,” says University of Southampton early modern history professor, Mark Stoyle, discussing the parliamentary pamphleteers’ evolving tactics in the English Civil War.

“It makes the Irish rebellion look even worse than it was. And it sort of raises even greater levels of bitterness and hostility towards the Irish. I would say those sorts of things had a very serious effect.”

The overarching lesson of history is that propaganda is baked indelibly into the human condition. Speech and lies come wrapped around the same tongue.

Stoyle says pamphlets printed during the English Civil War period also revived superstitious beliefs in witchcraft, leading to an upsurge in prosecutions and killings on charges of witchcraft which had dipped in earlier years under tighter state controls on popular printed accounts of witch trials.

“Once the royal regime collapses, the king’s not there to stop people prosecuting witches, he’s not there to stop these pamphlets appearing. There’s a massive upsurge in pamphlets about witches and in no time at all there’s a massive upsurge in prosecutions of witches. That’s when Matthew Hopkins, the witchfinder general, kills several hundred men and women in East Anglia on charges of being witches. And again I think the civil war propaganda has helped to fuel that.”

If you think modern day internet platforms don’t have to worry about crazy superstitions like witchcraft and devil worship just Google “Frazzledrip” (a conspiracy theory that’s been racking up the views on YouTube this year which claims Hillary Clinton and longtime aide Huma Abedin sexually assaulted a girl and drank her blood). The Clinton-targeted viral “Pizzagate” conspiracy theory also combines bizarre claims of Satanic rituals with child abuse. None of which stopped it catching fire on social media.

Indeed, a whole host of ridiculous fictions are being algorithmically accelerated into wider view, here in the 21st (not the 17th) century.

And it’s internet platforms that rank speech above truth that are in the distribution saddle.

Stoyle, who has written a book on witchcraft and propaganda during the English Civil War, believes the worst massacre of the period was also fueled by political disinformation targeting the king’s female camp followers. Parliamentary pamphleteers wrote that the women were prostitutes. Or claimed they were Irish women who had killed English men and women in Ireland. There were also claims some were witches.

“One of these pamphlets describes the women in the king’s camp — just literally a week before the massacre — and it presents them all as prostitutes and it says something like ‘these women they revel in their hot blood and they deserve a hotter punishment’,” he tells us. “Just a week later they’re all cut down. And I don’t think that’s coincidence.”

In the massacre Stoyle says parliamentary soldiers set about the women, killing 100 and mutilating scores more. “This is just unheard of,” he adds.

The early modern period even had the equivalent of viral clickbait in pamphlet form when a ridiculous story about a dog owned by the king’s finest cavalry commander, prince Rupert, takes off. The poodle was claimed to be a witch in disguise which had invested Rupert with magical military powers — hence, the pamphlets proclaimed, his huge successes on the battlefield.

“In a time when we’ve got no pictures at all of some of the most important men and women in the country we’ve got six different pictures of prince Rupert’s dog circulating. So this is absolutely fake news with a vengeance,” says Stoyle.

And while parliamentarian pamphlet writers are generally assumed to be behind this particular sequence of Civil War fakes, Stoyle believes one particularly blatant pamphlet in the series — which claimed the dog was not only a witch but that the prince was having sex with it — is a doubly bogus hoax fake.

“I’m pretty certain now it was actually written by a royalist to poke fun at the parliamentarians for being so gullible and believing this stuff,” he says. “But like so many hoaxes it was a hoax that went wrong — it was done so well that most people who read it actually believed it. And it was just a few highly educated royalists who got the joke and laughed at it. And so in a way it was like a hoax that backfired horribly.

“A classic case of fake news biting the person who put it out in the bum.”

Of course this was also the prince’s dog pamphlet that got the most attention and “viral engagement” of the time, as other pamphlet writers picked up on it and started referencing it.

So again the lesson about clickbait economics is a very old one, if you only know where to look.

Fake news most certainly wasn’t suddenly born in 2016. Modern hoaxers like Jones (who has also been at it for far longer than two years) are just appropriating cutting-edge tech tools to plough a very old furrow.

Equally, it really shouldn’t be any kind of news flash that free speech can have a horribly dark side.

The overarching lesson of history is that propaganda is baked indelibly into the human condition. Speech and lies come wrapped around the same tongue.

The stark consequences that can flow from maliciously minded lies being crafted to move a particular audience are also writ large across countless history books.

So when Facebook says — caught fencing Kremlin lies — “we just didn’t think of that” it’s a truly illiterate response to an age-old problem.

And as the philosophical saying goes: Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

That’s really the most important history lesson of all.

“As humans we have this terrible ability to be angels and devils — to use things for wonderful purposes and to use things for terrible purposes that were never really intended or thought of,” says Stoyle, when asked whether, at a Facebook-level scale, we’re now seeing some of the limits of the benefits of free speech. “I’m not saying that the people who wrote some of these pamphlets in the Civil War expected it would lead to terrible massacres and killings but it did and they sort of played their part in that.

“It’s just an amazingly interesting period because there’s all this stuff going on and some of it is very dark and some of it’s more positive. And I suppose we’re quite well aware of the dark side of social media now and how it has got a tendency to let almost the worst human instincts come out in it. But some of these things were, I think, forces for good.”

‘Balancing angels and devils’ would certainly be quite the job description to ink on Zuckerberg’s business card.

“History teaches you to take all the evidence, weigh it up and then say who’s saying this, where does it come from, why are they saying it, what’s the purpose,” adds Stoyle, giving some final thoughts on why studying the past can provide a way through modern day information chaos. “Those are the tools that you need to make your way through this minefield.”

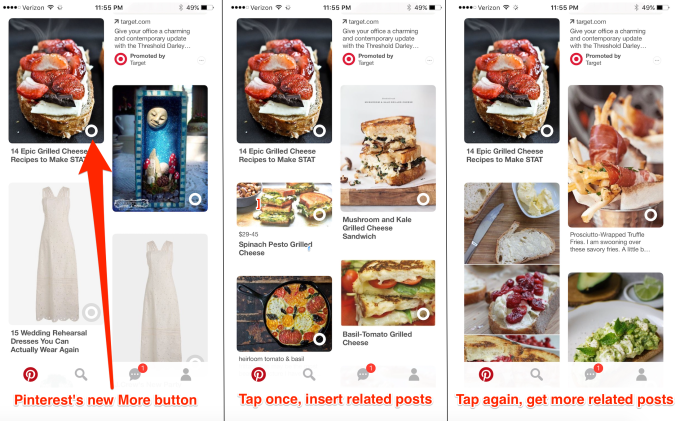

to foster engagement

to foster engagement  (@romaindillet)

(@romaindillet)